Brahms and Schoenberg at the New York Philharmonic

Maestro Alan Gilbert Tours the Leitmotifs

By: Susan Hall - Sep 26, 2009

This report covers the New York Philharmonic's 14,876th concert on Friday September 29, 2009, with Alan Gilbert, conducting.

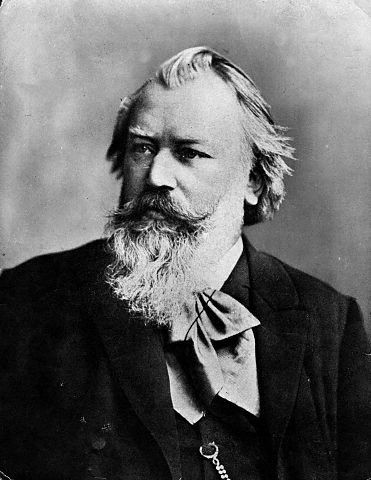

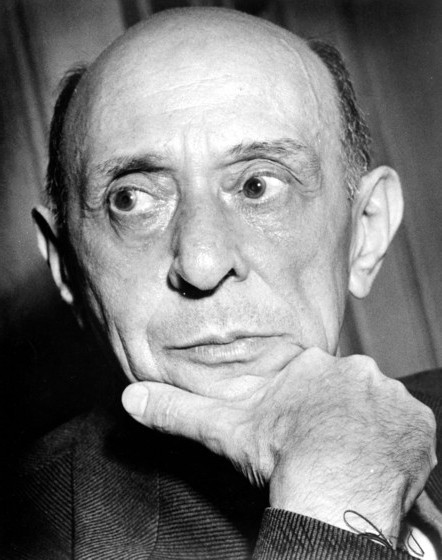

For this concert, Maestro Gilbert chose the Brahms Violin Concerto in D Major and Schoenberg's Pelleas and Melisande, mostly in D minor. When Maestro Gilbert pointed out the lietmotifs in the Schoenberg he connnected ths composer to Tristan and Wagner. For a long while, Schoenberg was considered an heir to Wagner, but in recent years his indebtedness to Brahms has also become clear. Organic composition -- looking always at the whole-- is a theme of both composers. Schoenberg was the first to recognize Brahms as a progressive force in music, but he also saw his own work a as part of the historic continuity.

Schoenberg always taught from classical examples: mainly Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms. He refused to teach any student who couldn't write in the style of Brahms. "If a student can't do that, I will not talk to him about new music under any circumstances, because he doesn't look at composition at all."

The two composers actually have a great deal in common. Both sought to expand the musical palette. Both men adhered to strict musical principles in composition, placing musical substance above style. Their contempories considered them too intellectual, yet both men were capable of composing music of great emotional power -- like the music in this program.

The Brahms violin concerto is considered the most difficult in the repertoire. One violinst called the work "unplayable", and another refused to play it because he didn't want to "stand on the rostrum, violin in hand, and listen to the oboe playing the only tune in the adagio."

When the work was completed, Brahms sent it to the foremost violinist of his day, Joseph Joachim, and asked him to report if any passages were impossible or too difficult and to "correct it, not sparing the quality of the composition". Joachim added a cadenza in the first movement, which was superbly performed on Friday by Frank Peter Zimmermann on a Stradivarius which once belonged to Fritz Kreisler.

The concerto's critics have never been silenced. Some say the violin's role does not stand out; others, that broken chords, rapid scale passages and rhythmic variation may be all fine and good for a pianist (Brhams was one) but the violin? Mr. Zimmermann played as though he'd never heard or had a complaint. All the difficulties were addressed with seamless brilliance and at the end there was a well deserved, ecstatic standing ovation.

Although he was one of the most influential composers and teachers of the twentieth century, Schoenberg was largely self-taught. He worked in a small private bank from 1891 to 1895. In 1894 he had paid a visit to a blind Viennese composer, Joseph Labor, for whom he played a movement of his C major string quarter. Labor is reported to have said calmly "You must become musician." Schoenberg's string quartet was then shown to a publisher who refused it: "You seem to believe that if the second subject consists of the first subject turned upside down and played backwards, the work is all right, come what may!" This remark does suggest the work's strict contrapuntal style, and is evidence of Schoenberg's great reverence for Brahms.

One day Schoenberg returned home from the bank and announced to his family: "I'm so happy. I lost my job......no one will ever see me inside a bank again!"

Maestro Gilbert gave us a tour through the leitmotifs in Pelleas and Melisande, which the composer premiered as conductor in 1905. He showed us where we might look for Wagner's Tristan, for Mendelssohn themes and Mozart's D minor mass. This symphonic tone poem was lavishly played by 17 woodwinds, 18 brass, 8 percussion, 64 strings and 2 harps. Schoenberg's future instrumentation would be in a new and looser style. Most of Pelleas is in D minor and is unique in its complex polyphony. Harmony and contrapuntal combinations of motives and chords built in fourths appear already from time to time

Those who have attended Philharmonic concerts for decades note that Yoko Takebe never smiled but now the Maestro's Mom is aglow, perhaps because she's the only member of the orchestra who won't be accused of being out of tune (a son can't do that), but more likely she is swelling with pride in this wonderfully talented young man.

When his back is to us, watching her face is like looking in a mirror of his -- everything that he brings to his subtle, compassionate interpretations are reflected in her face. On Friday, he did turn to us before Pelleas and Melisande was performed, and humbly made some suggestions of where to look for the various characters in the piece. Debussy had gone on to make an opera of the Maeterlinck play Richard Straus had called to Schoenberg's attention, but Schoenberg noted, "Had I written an opera, I would have missed the wonderful perfume of the poem."

We can look forward to being led on to new musical terrirtory by Maestro Gilbert. These are exciting times at the Philharmonic.