Americans in Paris 1860-1900

Museum of Fine Arts Boston 2006

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 25, 2013

Americans in Paris 1860-1900

Curated by Erica A. Hirshler, MFA, Boston, Kathleen Adler, National Gallery, London, and H. Barbara Weinberg, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Through September 24, 2006

Previously, National Gallery, London, February 22 to May 21, 2006

Next: The Met, October 17 to January 28, 2007

Posted to Maverick Arts Magazine, June 29, 2006

There is a critical mass of masterpieces ensuring that “Americans in Paris, 1860-1900” will be a blockbuster during its run at the Museum of Fine Arts, through September 24, before moving to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 17 through January 28, 2007.

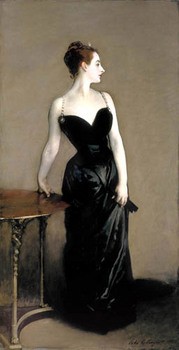

During a rainy day tour of the museum there was a substantial enjoying “Whistler’s Mother,” in a rare visit from Paris, as well as his “The White Girl,” from the National Gallery in D.C., Sargent’s ever stunning “Madam X” from the Met. There is an abundance of favorites by Mary Cassatt which warm the hearts of women and children. Add to this tough and realistic Eakins on loan from Philadelphia. Then a couple of dandy Homers including the wonderful “Prisoners from the Front” a curiously static Civil War painting from the Met, as well as other popular favorites of 19th century American painting.

While the masterpieces were judiciously dispersed drawing us from gallery to gallery, there were too many works by minor artists familiar only to scholars in the field. The exhibition may be satisfying to tourists and casual visitors. For MFA regulars, however, there is a sense of déjà vu. Once again the MFA is recycling works from storage while rehanging the permanent collection to flesh out a traveling show.

With the exception of a few centerpieces much of the work in the current exhibition has been reshuffled from prior MFA exhibitions including “The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930,” curated by Trevor Fairbrother in 1986, and Erica Hirschler’s 2001 exhibition “A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940.” Once again the museum is glorifying Boston's Brahmins daubing away in Paris or spinsters like Ellen Day Hale channeling George Sand in the ersatz “flaneur” pose of her butch self portrait. The Hale, now in the permanent collection of the MFA, was the “star” and “discovery” of Hirschler’s feminist “Studio” show.

The real problem, yet again, is that the MFA with its fixation on the “Elegant Age” (when artists including Sargent and Hale were still in the closet) just doesn’t go far enough. Imagine if they had expanded the theme of “Americans in Paris” to the 20th century and the Lost Generation? That might have included some honest to gosh gays and lesbians like Gertrude Stein (wouldn’t her portrait by Picasso have looked terrific in the Gund Galleries?) her friends the Provincetown, White Line printmakers, Maude Squires and Ethel Mars, or even Cole Porter. The museum might have included the wonderful and clever Gerald Murphy who inspired his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald to state that “The rich are different from us.” How about Man Ray? Or Patrick Henry Bruce? They could have piped in Gershwin’s “Americans in Paris.” But no. Once again we have to slog through the time, prior to the Armory Show of 1913, when American culture, with a few exceptions, was hopelessly provincial or marrying impoverished European aristocracy. That phenomenon is well conveyed in Edith Wharton’s “The Buccaneers.”

For now, let us count our blessings. What’s not to like about having Whistler’s “Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother” (1871) as a summer long visitor from the Musee d ‘Orsay? It was, at the time, one of only a few works acquired by the French, state run museums by a living artist, let alone an American. Another was Winslow Homer’s haunting and enigmatic “A Summer Night” (1891) that shows two women dancing against a background of moonlit surf. It is also on loan from Paris.

Bostonians can never get enough of John Singer Sargent and this time we are treated to his most intriguing painting, the one that almost ruined his career. Today “Madam X (Madam Pierre Gautreau)” (1884) is so familiar that it is difficult to comprehend why the portrait caused such a fuss. Virginie Avegno (1859–1915) was born in Louisiana, the daughter of Major Anatole Avegno of New Orleans, a gentleman whose family had emigrated from Camogli, Italy, and Marie Virginie de Ternant of Parlange Plantation, Louisiana. After Major Avegno died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Shiloh, Mrs. Avegno took her daughters to Paris. There Virginie became a celebrated beauty and married Pierre Gautreau, a Parisian banker. The last time the painting was in town, ages ago for a Sargent show, Virginie Gautreau was mounted as a pendant, next to a smarmy portrait of her alleged lover, Dr. Samuel John Pozzi. The prominent Parisian OBGYN is depicted wearing a spectacular red robe. Trevor Fairbrother published an article about the painting demonstrating that when first exhibited in Paris, one of her jeweled straps was provocatively dangling off her shoulder. A wag quipped that her daring décolletage was the most dramatic feat of French engineering since the Eiffel Tower. Under pressure from her husband Sargent repainted the strap and kept the (unsold) painting in his possession. Sargent left Paris to relaunch his career as a portrait painter in London and Boston.

Yes there are wonderful Cassatts in this show. Lots of them. She was indeed a marvelous painter. Her style is comparable to that of her friend (they had a complex relationship) Edgar Degas. But, like most of the Americans of her generation in this show, there was more style than substance in her work. There just isn’t a lot of variety or imagination to all those pretty pictures of women and children.

Rich Americans flocked to Paris in the hope of acquiring culture and style. But when Isabella Stewart Gardner, a New Yorker married to Jack Gardner, a proper Bostonian, arrived back home from the grand tour with the latest Paris fashions the Brahmin women responded that “We have our hats.”

There are tantalizing glimpses of young Americans living la vie boheme. As well as a couple of examples of works by an African American expatriate, Henry Osawa Tanner (1859-1937). If only the paintings were more interesting. His major picture in this show “The Young Sabot Maker” is well crafted but uninspired.

As is often the case many of these artists were more interesting for their social and sexual adventures than for the work that resulted from living abroad. Whistler, for example, is far more fascinating as an outrageous, avant-garde character than compelling as a painter. One of his best works “Symphony in White, No. 1, The White Girl” (1862, the National Gallery, Washington, DC) has a fascinating back story. It depicts his spectacularly beautiful Irish mistress Josephine Heffernan. It was rejected by the Salon but included in the famous Salon des Refuses of 1863 where it was a great hit. This assured the young artist a footing in the Parisian art world. He was befriended by the painter Gustave Courbet, and Whistlerintroduced him to Jo. Then Whistler took off for an adventure in South America. When he got back to Paris he had been cuckolded by Courbet. The artist not only stole his girlfriend but included her in a scandalous painting in bed, nude, sleeping with another woman. Whistler, like Sargent somewhat later, was laughed and booed out of Paris and regrouped in London.

But, that’s another story and potential exhibition "Americans in London."