Robert Rauschenberg Combines

Metropolitan Musseum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 23, 2013

Robert Rauschenberg Combines

Organized by Paul Schimmel

For the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Catalogue: 318 Pages. With essays by Schimmel as well as Charles Stuckey, Thomas Crow, Brandon W. Joseph and an Afterword by Pontus Hulten

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

December 20 through April 2, 2006

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

May 21 through September, 2006

Musee national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

October 25 through January 21, 2007

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

February 17 through May, 2007

Reposted fromm Maverick Arts Magazine, March 29, 2006

Now in its last days at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Rauschenberg Combines is the most exquisite, timely and insightful monographic exhibition of a living contemporary artist of this or any other year. Despite a stroke, the artist, who was born on October 22, 1925 in Port Arthur, Texas, continues to produce new work. He may be compared to a shark that has to keep swimming to stay alive. Overall, his oeuvre may be the most extensive of any American artist of the 20th and now 21st centuries. Clearly there are critical debates regarding the issues of quantity vs. quality. Some would argue that the legacy of Jasper Johns, a notably slow and methodical artist, point by point, and, object by object, overall, may be a far greater artist. What that means, however, is that Jasper made fewer mistakes and may have been more cautious, consistent and deliberate. It is often stated that the oeuvre of Rauschenberg needs editing. That it includes a plethora of flops and studio droppings. The epic, 1997 retrospective at the Guggenheim, that was installed uptown as well as downtown in New York, tended to overwhelm and engulf the viewer. There was often the sense of wading through the output. That the artist was bludgeoning you into a state of submission.

But in this more manageable, neat and concise selection of combines created from 1953, through the end of the series “Gold Standard,” 1964, the artist was second to none. It is significant to observe, however, that, from the vantage of hindsight, the most compelling and riveting examples of the series tend to date to its beginnings. They are the most inventive, galvanic and edgy pieces. By the end of the series, as is so often the case with great innovations, the artist, unfortunately, knew what he was doing. The works from 1961 on to my sensibility seem formulaic. It was a matter of Rauschenberg creating Rauschenbergs. After facing the most inspiring and daunting challenges there is a moment when an artist enters the studio knowing what he is doing. It is the end of the risk taking. Too often this is complicated by applause, critical, curatorial and from the market. The artist evolves from bohemia and privation to celebrity. The work sells so the artist gets paid and laid. Which is perhaps great for the artist but a disaster for the work.

The greatest artists, the masters, an elite of which Rauschenberg is a charter member, have to fight through the groupies to recover the sanctity, isolation and horror vacui of the studio. The artist needs to recover the creative jitters, the fear and trembling of navigating terra incognita, where medieval maps were inscribed with the legend “hic transit dracones.” He would do this constantly in his career. Those moments of retrenching and realignment. Like the move to Captiva Island in Florida when he escaped the noose of the city. No more dumpster diving for materials on trash night. Instead, gathering shells and coconuts on the beach. Mailing mangoes to his friends. Making huge iris prints and rubbing them onto expanses of canvas. Taking back the night of his own work.

For me, the work of Rauschenberg has always been personal. The first work of the combine series I encountered “Odalisk” (1955-58) occurred in the early 1960s when I was an installer for the Exhibits Librarian at Brandeis University. There was a traveling show on the theme of Neo Dada art. The piece came in an elaborate hard case which we carefully unpacked. At the time, the container seemed even more complex and interesting than what it contained. The piece, now owned by the Ludwig Museum, seemed strange, comic and even absurd. It was hard to take seriously. Was that really a stuffed chicken perched on the top of a flimsy box covered with collage and splashes of paint? How and why was the narrow base of this construction piercing a pillow painted white? There was nobody to explain it to me but it has been stuck in my head all these years. What a jolt for a young guy being taught art by professors whose ideas were as old as they were. Nobody wanted to talk about this brash new work. The professors were teaching us how to be social realists and abstract expressionists. But this piece really rocked my boat and nobody wanted to discuss it. How art school.

Later, when Brandeis opened the Rose Art Museum, its founding director, Sam Hunter, launched the collection by buying about 25 new works with about $50,000 given to him by the Mnuchin-Gervitz families. At the time, a lot of crazy stuff, which, again, my professors didn’t want to talk about. Sam bought Rauscheberg’s “Second Time Painting” from 1961, with its real clock, that puzzled me at the time. Today, I regard it as a good but not great combine.

What are the great ones? Well, you would have to start with the free standing, screen like “Minutiae” (1954) which he created as a prop for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Bob was traveling with Merce and John Cage in a VW Bus as a member of the company at the time until there was a later falling out. He would go on to work with dancers and performing artists brilliantly off and on for the rest of his career. I first saw this piece in an Art and Dance exhibition at the ICA some years ago. It was love at first sight. Less so for the first encounter with “Bed” (1955) now in the collection of MoMA. At the time it didn’t make sense that the artist would smear paint on his own bed and “ruin” a nice old quilt.

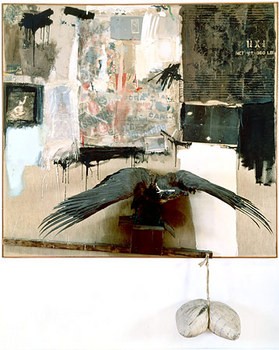

Some of the greatest pieces like “Canyon” (1959) with its stuffed eagle projecting from and a tied up pillow hanging from the picture plane I encountered much later, because it was in the private Sonnabend collection, and rarely shown. Similarly, I first viewed the famous and controversial “Monogram” (1958-59) with its stuffed angora goat, with a tire around its middle, when it was loaned to the Guggenheim retrospective. Early on, the piece was acquired by the Moderna Museet, in Stockholm which I have yet to visit. Owning such a seminal work, which it is lending to this show, was unquestionably the bargaining chip that was key to being included in the four museum itinerary for this major exhibition.

Surely, I feel truly blessed to have had the opportunity to see once again, in depth and context, such remarkable work. The images and constructions have been sign points and marks on some internal map of artistic vision. This great project has allowed for connecting the dots and coming to some conclusions.

The early works now look vintage and fragile. The ephemeral found materials must present nightmares for owners and their conservators. How to preserve works that when created spontaneously a half century ago would come to be regarded as the priceless icons of the avant-garde of their time. You sense that the very young artist was having fun with a wild sense of invention. Putting ties, bedding, tires, stuffed animals, clocks, fans, and cut up magazines he picked up off the street into the work.

There was a wonderful, serendipitous joy to such creativity. Perhaps it made no sense. Then, the ultimate iconoclast, he “ruined” and damaged these “precious objects” by smearing them with paint in a knowing and coy mockery of the ever so serious gesture of the abstract expressionists who came before him. It was a playful “up yours” gesture. He was, at the time, the new kid on the block willing to mock and push aside the established artists. Just as he is now ripe for the taking by the neo punk, snotty kids who are probably visiting the Met, viewing the work, and hatching schemes to rip off the brilliant combines.

-----