Maya Lin Beyond Vietnam Memorial

Lecture at Harvard University

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 23, 2013

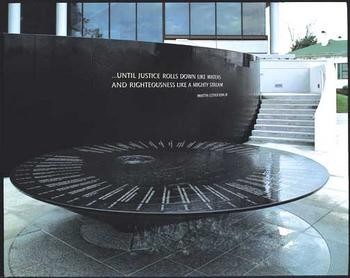

Introducing Maya Lin to an overflow audience at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts professor Louis Menand established some background and boundaries. That she would not discuss her most famous work, the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, dedicated in Washington, D.C. in 1981, designed when she was a 21-year-old senior at Yale University and winner in a competition with 14,000 entries. Or her other memorials including the Women’s Table for Yale, 1993, and the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center, Montgomery, Alabama, 1988-1993. Menand emphasized that Lin has been blessed and limited as the most famous maker of memorials of our time. He emphasized that she might have exploited her reputation, as many would have been tempted, but instead has grown to become a diverse creator of site specific sculptures, museum installations, corporate design interventions (including lobbies), and architecture ranging from residential to major projects such as the soon to be built Museum of Chinese Art (MOCA) for Chinatown in Lower Manhattan.

Menand explained that the format for the evening would begin with a brief presentation of slides of recent work, with little or no comment. This proved to be neither brief nor without comment. Followed by a dialogue between the two of them, then a few questions. The slide aspect would focus on recent work in architecture, sculpture and an overview of arguably the most ambitious and potentially greatest project of her career thus far, The Confluence Project, which entails seven sites along 450 miles of the Columbia River Basin in Washington and Oregon in recognition of the 200th anniversary of the explorations of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Lin stated that for many reasons she does not want to be in the memorial and monument business. It is not difficult to imagine the trauma she endured when her design for the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial was bitterly opposed by veteran’s groups and politicians. Some compromise was reached when a second, more traditional group of life size, bronze soldiers was placed near but not interfering with her design. Of course, a generation later, her design with 58,000 names inscribed on a broad wedge of black granite, opened at a 125 degree angle, has become the paradigm for all subsequent monuments. As testament to the success and impact of her simple and elegant design the memorial attracts an average of 10,000 daily visitors. For anyone, including myself, who has ever spent time in front of the wall and scanned the columns of names it is an indelible experience.

It is ironic that what initially was so provocative and widely opposed, including cruel racism and sexism targeting a young Chinese-American woman, would eventually prove to be a magnificent triumph. But, what to do next? How to wiggle out from under such a defining shadow? Particularly, at the beginning of a career in the arts. Consider that it was subsequent to the completion of the project that she went back to Yale to pursue a degree in architecture.

The evening at Harvard provided a succinct and compelling overview of how the work has developed since then. To be frank, my responses to much of what she presented are mixed. The earthwork, site specific pieces appear derivative of other sources, from the Native American mound works of her home state, Ohio, and earth works by Robert Irwin, Robert Smithson and James Turrell to mention but a few. Her projects do not compare to these artists and sources in their originality or finesse. They don’t demonstrate the command and feeling for form that one expects in a great sculptor. The works seem more cerebral than visual. The museum and gallery sculptures are cold and brittle. They navigate the terrain between formalism and minimalism with references to earth science. One of them evokes topographical mapping of the ocean floor transformed into a floating grid of wires attached to walls and suspended over a space. She describes these works as “sketching.” Later, when asked if she used computers for her designs, she responded that she did not and was of another generation rooted in drawing and model making. But added that her staff is computer literate.

Again, the architecture that she projected seemed interesting and inventive but limited in scope and form. It is too tempting to speculate if we would be packed into an auditorium, or in a jammed second space viewing the lecture on a large video screen, were we not lured there by the prospect of gaining insights about the creator of the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial? Perhaps that is harsh and unfair; too obvious, but also terribly true. Taken apart from her famous monuments, arguably, the sculpture and architecture are not on a level with equally famous peers. Although the Langston Hughes Library in Tennessee, 1999, for which she jacked up and built into a vintage structure on the former Alex Haley estate, is clever and interesting. She preserved the outer shell of the found building while providing a functional, modern interior.

As she spoke in a deep resonant voice, full of gravitas and intensity, Lin exuded the aura of a diva. One who has learned to say no to many requests and projects. An individual who has created an aura and shield to protect the vulnerable persona of a wife, mother and creator. Who just wants to do her best work. To fulfill her own expectations; made all the more difficult by achieving daunting fame even before learning and mastering the fundamentals of her profession.

Having completed three memorials she conveyed that she hopes to design one more project “Extinction” before retiring from the monument business. During the dialogue with Menand she was lured into making comments on her views of designing monuments and memorials. It was presented from the perspective of acting as a juror in the competition for a memorial for the Ground Zero site of the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. While she declined to submit a design she presented disclaimers of her views and positions to the committee prior to accepting responsibilities as a juror.

Lured into discussing that process she offered remarkable insights about how she came up with the design for the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial. As a part of the competition prospectus it was a stipulation that designs must include the names of all of the dead. This was, of course, a perplexing specification without precedent on that scale. She discussed how, prior to this competition, there had been short lists of names in memorials of small towns in America commemorating its citizens who had fallen in wars. But there was no precedent for incorporating 58,000 names into a design. She explained that the stumbling block was the approach of first creating a compelling form or shell and then putting names on it. Her approach entailed starting with and focusing on the names and then finding a support for them. Her solution was remarkably simple and elegant. For some on the engineering and architectural team that executed the project, too much so. They complained that her “veneer of stone was not really a sculpture which is what the project seemed to require.” Indeed, the memorial is less a sculpture than a design. Perhaps that is her brilliance and originality.

It is when she is challenged to fuse the expectations of memory, respect for the dead and martyrs, then combining these elements into a visual presence that she is at her best. Perhaps, this is precisely why the pure sculptures and installation works lack resonance. Because they lack the confluence of form and content. Without that added aspect the forms themselves are unremarkable and derivative.

It is precisely this balance of strength and limitation that gives promise that the Confluence Project may ultimately be her greatest work since the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial. It entails so many complex historical and site specific issues that it represents a formidable challenge and the opportunity to secure her position as a true master of our time.

Significantly, at the outset, she wanted no part of the project to commemorate the Corps of Discovery and the epic adventures of Lewis and Clark and their group of 33 men and a woman. Surely, given the subsequent history and the horrors of Manifest Destiny, the first contact between white men, sent there by Thomas Jefferson, and the 17 tribes they encountered in their trek to the Pacific Ocean, is hardly cause for celebration. She was not interested in promoting tourism or placing her sculptures on the sacred land of native people or the National Parks. So she said no, over and over. Until she finally responded to the appeals of tribal councils and their pleas to work with them. At Harvard, she showed maps and photographs of the sites and discussed some concepts for the epic project. Much of what she conveyed was about what she would not do; to inflict no harm on the land and its indigenous people. Her plans involve restoring the natural ecology of the ruined landscape: Replanting and reforesting, undoing dams along the rivers, getting rid of parking lots, generic buildings and playing fields.

The challenge of her intention is to weave together passages from the writings of Lewis and Clark, to celebrate their efforts as naturalists, while simultaneously evoking the native people, their history and traditions of creation. This entails interacting with the survivors of tribes they encountered: Arikaras, Assiniboins, Blackfeet, Chinooks, Clatsops, Hidatsas, Mandans, Missouris, Nez Perces, Otos, Shoshones, Teton Sioux, Tillamooks, Walla Wallas, Wishrams and Yankton Sioux. The sites chosen for the $22 million project include Cape Disappointment State, Frenchman’s Bar Park, Fort Vancouver, Sandy River Delta, Celilo Falls Park, Sacajawea State Park and Chief Timothy Park.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase initiated by Jefferson doubled the size of the United States. The West Coast, South West, Texas and Alaska would later be bought or seized from Spain, Mexico and Russia. It is all a part of our bloody history. Napoleon Bonaparte at the time needed the money and had lost Haiti in 1801 to the slave rebellion of Toussaint L’Ouverture. He sent a force to reclaim the island but it suffered massive losses particularly to fever. With the defeat of its presence in the Caribbean the city of New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory became expendable. Napoleon sold it for $11,250,000 and the US pledged another $3,750,000 to cover debts of France to claims of US citizens. So Lewis and Clark were dispatched to explore and report back to the President exactly what had been acquired for $15 million.

Were it not for the guidance of the native woman, Sacajawea, the 17-year-old wife of a Frenchman recruited for the project, and the support and compassion of the people along their long and difficult route, the group would never have survived to make their report to Jefferson. Others would follow and contribute to the American Genocide that would destroy not just the indigenous people and their way of life, but cause irreparable damage to their sacred land. Lin commented how where once the river was clogged with millions of salmon during spawning season now there is just a trickle of some 250,000 that make it up river. As a part of her design, she hopes to record the numerous species that Lewis and Clark documented “They were incredible naturalists” and to record their current status.

What’s done cannot be undone. The land will never be what it was. But the Confluence Project will be no Disneyesque theme park for tourists. Lin hopes and plans that it will be a place for Americans to gather and reflect on their brutal past as well as hopes for peace and a gradual restoration of nature and peoples for future generations. For the artist this will be her greatest challenge and most enduring monument. Because it combines both respect for the past and hope for the future.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine December 4, 2005