2004 DeCordova Annual Exhibition

Evoking Perennial Questions

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 22, 2013

The 2004 DeCordova Annual

Artists: Leslie Bostrom, Sean Foley, Beth Galston, William Hosie, Henry Kaufman, Brian Knep, Mary Lang, Sandy Litchfield, Toru Nakanishi, Gil Scullion, Al Souza, Sandy Winters

Curators: Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, Nick Capasso, George Fifield, Alexandra Novina

June 12 through September 5, 2004

DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park

Lincoln, Massachusetts

Being included in a museum group show for the artists in question is much like real estate. What is the difference between being the best house in a bad neighborhood, or the poorest house in a good neighborhood? Similarly, is it better to be an outstanding artist in a mediocre show or a mediocre artist in a strong exhibition?

Why does the 2004 DeCordova Annual Exhibition evoke those perennial questions? The annual surveys of the art of New England, the mandate of this regional museum, have proven to be consistently inconsistent. These non-thematic surveys have sampled from several categories: Painting, sculpture, photography, technology and new media. There is a commitment to look at work produced in the entire New England region and to include emerging, mid career and established artists. All very high minded and well intended but we are all familiar with the paving of the path to hell. Once again the DeCordova staff, which insists that it works by consensus, has delivered a hell of a show.

It is not so much that the 2004 Annual is bad. No, what is worse is that it is just boring. Rather than loving or hating the exhibition, and selection of individual works, one just emerged with a gnawing sense of apathy. From the point of view of a critic any emotion is preferable to none.

During the crowded vernissage there was remarkably little buzz. It is always fun to be out and about. Those rare occasions when you get to attend a big crowded social event with a good chance of running into friends and enemies. As usually occurs when critics attend such occasions, there were attempts by artists and colleagues to lobby for their friends. Or to tip off the reviewer with insights about work that might be overlooked. But the energy level of this familiar discourse was remarkably underplayed. Virtually nobody whom I encountered was excited about anything. The most consistent and generic comment, quickly offered without restraint, was how bad the paintings were. With just a bit of quibbling here and there.

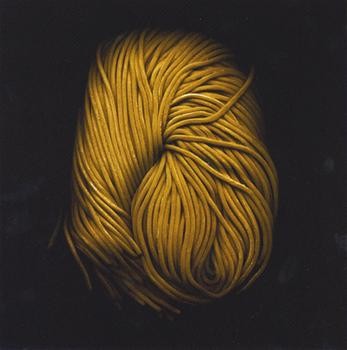

There was just nothing to get excited about. The mix included some work that one might respect and enjoy seeing in another context. Beth Galston, for example, is a master of media and installation work. Her work here, a blackened room with a garden path curving through beds of illuminated blossoms hovering on long thin metal stems, hovering and swaying in a gentle breeze, was representative but not, for me, her strongest piece. But clearly she is an artist whom one respects. And the clear hit of the evening, if one may make such a statement in such an enervating context, were the digital prints of combinations of ramen noodles, scanned directly on a flat bed, by Toru Nakanishi. Everyone seemed to enjoy the images which were clever, insightful and delectable. The artist will surely benefit from this exposure and popularity.

But having said that, now what? It is tempting to just cut and paste hunks of text from my reviews of the Annual last year and the year before that and the year before that and the year before that. There is little wonder why I am not warmly greeted by the curators. If you do your job in an honest and passionate manner, most critics are not popular with curators. The contemporary curator of a major Boston museum was outright nasty to me during a chance encounter last week at a gallery. As a colleague and mentor told me early on when I was taking a beating for some of my writing, “Charlie, in this business, you have to have elephant hide.”

Truth is most of us would prefer to win friends and influence people. I even read that Dale Carnegie classic as a teenager and vowed to follow its suggestions. But that just got botched. Hey, stuff happens. Any normal person would rather be liked than disliked. Except critics. Well, some critics. For example, there was a striking difference between reading the reviews of this exhibition in the Boston Globe, damned with sweet but faint praise, by Christine Temin, and stomped on with hob nailed boots by Christopher Millis in the Boston Phoenix. It was delicious vintage Millis. Oh boy.

The notion occurred to me to just pass on writing this piece. Why flog the DeCordova, and their enervating programming, over and over. Is there any useful purpose to making the same point repeatedly? Doesn’t it get rather Ciceronian? There was another idea of just listing the names of this year’s artists and a blank text. More than likely the same conundrum will occur next year, and the year after. Or for as long as the same director, curatorial team and format remains in place.

The issue here centers on the concept of regionalism. To carve out a hunk of geography and proclaim this is my domain and mandate. There is much to praise in that approach as the majority of other major contemporary arts presenters seem to go out of their way to ignore what is being produced under their nose. If it is local it just can’t be good is the familiar notion. The other negative aspect of regionalism is that it implies cronyism. The institution and curators because of their well defined turf enjoy power and privilege. At least within their domain.

It then becomes the matter of the quality of one’s realm. The Whitney Biennial, for example, is a very provincial and regional show. The curators make only token gestures to look at the art of America. The vast majority of the work is drawn from local galleries. But, heck, we are talking about New York, the epicenter of the international art world. Similar arguments might be made on behalf of curators in Chicago or California. But, New England? That gets dicey.

On the other hand, I am a committed New Englander. It is where I live and work. I am curator of an exhibition program at the New England School of Art and Design at Suffolk University. Our exhibitions are focused on locally produced art, with a mix of national and international shows, and I am very proud of the work we have presented. Indeed, a number of the artists I have shown have been included in DeCordova and other museum exhibitions. I regularly visit and write about Boston and New England based gallery and museum exhibitions many of which are of truly global significance.

While I am proud to be a part of a vibrant and inspiring arts community why do I not find that reflected in the programming of the DeCordova and its standard bearing Annual? Were I a curator or critic visiting from some other region or nation would I be willing to write off New England based on the mediocrity of the work presented in the Annual?

Truth is we all have bad art days. It can happen anywhere at any time. Or in any period of art. When we see a bad Whitney Biennial we do not conclude that contemporary American art at that moment sucks. We just conclude that, once again, it is just a bad Biennial. Although this time most people remarked that it was not that bad, or better than usual. A bad art day might include slogging through rooms of 17th and 18th century Italian painting in a major European museum. Or the French rococo other than Boucher and Fragonard. Or most American painting until 1945. Or a museum of Czech icons. Or most galleries on Newbury Street in any given month. Or most galleries in Chelsea on any given month.

The fact is that there is more bad art than good art. Most art is just art and not much more than just art. What I want, what I have given my life for, is that something more. That something more than just art. It happens rarely and you have to know where to find it. It is about the passion of the hunt. Like that Hemingway story I read recently about a man’s hardship and quest for the perfect trout stream. That story was art and it was more than art and more than trout. It was about trout. Which is something that doesn’t interest me. But Hemingway made me interested in trout, passionate about trout. It became a vision quest. And that interests me. The author hooked me. Anything else is just fish.