Warhol Profiled on PBS

Four Hour American Masters by Ric Burns

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 22, 2006

"Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film" Directed by Ric Burns; written by James Sanders and Burns; narrated by Laurie Anderson; directors of photography, Buddy Squires, Peter Nelson, Allen Moore, Michael Chin and Don Lenzer; edited by Li-Shin Yu and Juliana Parroni; music by Brian Keane; produced by Donald Rosenfeld, Daniel Wolf and Burns; released by Steeplechase Films, Mr. Wolf, High Line Productions and Thirteen/WNET New York.

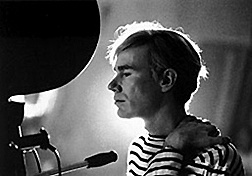

There appear to be a major point and strategy in the four hour biography "Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film" by Ric Burns that aired for the past two nights on PBS. First that Warhol was The Genius of the art of the second half of the 20th century. Picasso is acknowledged as dominating the first half. And that, in crafting his project, unlike prior documentaries Burns opted not to involve the motley crew of hangers on, gallerists, other pop artists, drug addicts, socialites and drag queens who have cavorted through other treatments while renewing their fleeting fifteen minutes of fame. These suspect characters are replaced by talking heads culled from academia and the post modern art world, most of whom, had little or no direct contact with the artist.

With the exception of Bill Name, an A head, designer of the silver factory, its concierge and conduit of the low life and riff raff who shared his passion for speed and Maria Callas, and a couple of too brief moments with Paul Morrisey who actually directed most of Andy's "commercial" films. There is strangely little direct contact with the enigmatic artist. Well also, Bob Colacella, who "worked" for Andy as editor of Interview and was involved in the staffing of the late studio. While Burns plods along carving out his "genius" thesis for most of the four hours the pace is leaden. There is, however, a mass of detail such as the precise sequence of what led up to the attempted 1968 assassination of Warhol by the frustrated, deranged, playwright and feminist, Valerie Solanas. She was the only member of her organization SCUM (Society to Cut Up Men). Literally. We learn step by step just how Warhol was shot through eight vital organs (but not the heart) and was pronounced dead for about a minute and a half before a surgeon cracked the chest and massaged the heart followed by five hours of repairing organs.

Remarkably, Warhol survived but greatly impacted physically and mentally. In a sense he bought back his life and that meant sweeping changes. The years that followed until his death by medical negligence on

Most of the Burns approach appears back loaded. The first two hours drag on with excruciating detail focused on his sickly childhood and humble origins as the child of Czech Catholic parents in

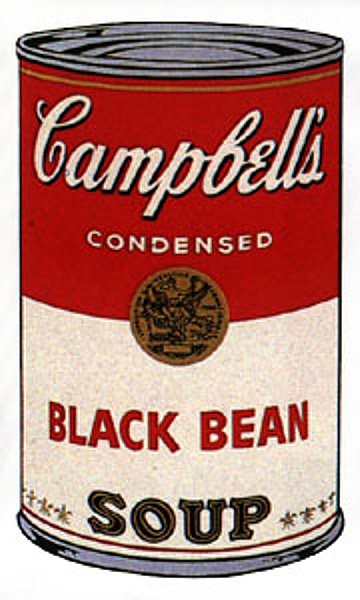

Burns shows us a lot of the commercial work which has not been well treated by critics and curators. We learn that he was dubbed "Raggedy Andy" for his habit of schlepping around his work in brown paper bags rather than portfolios. The transition from commercial to fine arts was complex and it is there that Burns is most insightful. In view of his later success it is interesting to learn just how much rejection and resentment his transition to the art world represented. He was hurt and snubbed by the leading Pop artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg whom Burns outs as lovers. Although "gay" they were careful to conceal their sexuality and distanced themselves from the swishy, campy Warhol. He was championed by Met curator, Henry Geldzahler, who died in 1994, and the art dealer Ivan Karp, who worked for Leo Castelli. Initially, Castelli rejected Warhol but took him on after the great success of a show at Stable Gallery. Burns never allows Karp to speak about Andy. The single verbal presence of Karp is a brief news clip after he was shot. Instead the only dealer we meet is Irving Blum who showed the seminal

When Warhol did start to click, and there was a demand for work in more and more shows, two simultaneously at the start of one season, he moved the studio and hired a young art student, Gerard Malanga, who knew how to make silk screens. Gerard worked with Andy to make hundreds of sculptures- Brillo, Kellogg's, Mott's and other boxes- as well as the large Elvis paintings and other important works. Malanga was also a key figure in the transition to the film work especially the 500 or so "Screen Tests." He was a character in many of the films and performed the Whip Dance when the Factory created the Exploding Plastic Inevitable a multi media show with the Velvet Underground at the Dom in Saint Mark's Place.

Prior to the airing this week I called The G, a friend of many years, and asked for comments about the Burns documentary and his role in it. "I am conspicuous in my absence," was Malanga's surprising response although he had contributed some archival footage and several stills to the production. He stated that he hadn't yet seen the documentary and doesn't have a TV in upstate

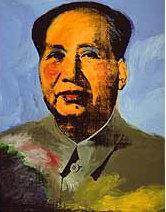

Excluding Gerard puzzled me. Why would Burns provide so much air time to Billy Name, as spokesperson for the Factory era, and freeze out The G, the publisher of many books of poetry, an internationally exhibited photographer, archivist, and one of the most intimate and insightful of Andy's collaborators. Just how did this provide insights to the flawed strategy and agenda of Burns. It underscores that other than making this tediously long and detailed documentary Burns knows nothing about contemporary art. So he limited the scope of his research and reporting to bludgeon home his flimsy notion of "Genius." He may be correct but the thesis holds little water without properly understanding his working process, which The G might have illuminated, or the testimony of peers and fellow "geniuses" Johns and Raushenberg. They were probably greater "artists" but Warhol eclipsed them in the category of "aura" by defining the cultural zeitgeist of the '60s in

Burns underplayed the role of George Plimpton. He assembled a brilliant and eccentric book, all quotes no narration, on the tragic life and death of Warhol super star, Edie Sedgwick, who flamed out at 28. While Plimpton is the kind of credible witness that Burns aspired to he never gets enough air time to stretch out effectively. There is so much more he could have told us about how Andy failed to intervene and take responsibility for followers who were falling all around him. The death rate of Andy's entourage was appalling. He was incapable of connecting to or caring about the tragedies of those who loved and trusted him. It was a trait he shared with other "geniuses" from Einstein and Picasso to Benny Goodman. When people asked about his by then deceased mother, for example, he would say "Oh, she's at Bloomingdales." It was his stock response to death and separation. The drag queen Ondine dubbed him Drella which was a conflation of Dracula, the blood sucker, and the fairy princess, Cinderella. There were those, like Edie and Valerie, who needed something from him other than meals on the tab at Max's

What mostly gets left out of this project is the art, other than hit and miss emphasis, and Andy himself. He is the ghost and unseen presence in his own documentary. There is a lot of available footage but Burns opted not to use it. Perhaps the real Andy would get in the way of the one he fabricated. There were fascinating details and insights but also a sense of missed opportunity. One of the experts employed by Burns keeps stating that Andy had no gift for narrative in his deadpan films many of which were real time, virtual reality still lives like "Kiss" "Sleep" and "Empire." Mostly his films had no plot and the actors improvised with a minimum of direction.

But actually it is Burns who lacks a gift for narrative. He had a great story to tell and blew it even with four hours of air time. This could have been the story of any "Genius." Burns stretched fifteen minutes into four hours. That's just not Andy.