Rethinking Landmark 9 Evenings

9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre and Engineering, 1966

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 19, 2013

9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre and Engineering, 1966

MIT List Visual Arts Center

Cambridge, Mass.

May 4- July 9. 2006

Guest Curated by Catherine Morris. The Artists: John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Oyvind Fahlstrom, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, David Tudor, Robert Whitman. The Engineers, organized by Billy Kluver of Bell Laboratories included: Dick Wolff, Herb Schneider, Larry Heilos, Jim McGee, Peter Biom, Cecil Coker, Peter Hisch, Robby Robinson, Fred Waldhauer and Harold Hodges. Original event occurred at the 69th Regimental Armory in New York City, from October 13-23, 1966. The Exhibition Catalogue: Includes introductions by Jane Farver and Morris with essays by Morris, Clarisse Baridot, Michelle Yi-Ann Kuo, original reviews by Lucy Lippard and Brian O’Doherty, and an interview with Herb Schneider. Published by MIT List Visual Arts Center. 88 Pages, illustrated.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine, May 9, 2006

The dense and daunting exhibition at the MIT List Visual Arts Center guest curated by Catherine Morris “9 Evenings Reconsidered: Art, Theatre and Engineering, 1966” represents an experiment in the archaeology of the avant-garde. The installation gathers the vast and insightful but also often undecipherable shards, artifacts, apparatus, photographs, drawings, diagrams, correspondence, and documentary film footage that provide information and input but little if any comprehensive understanding of a series of ten individual works that, although wildly uneven on every level from aesthetic to technical, have entered the canon of performance art, experimental music and theatre, bridging the gap from the eras of Dada, Fluxus and the Happenings/ Actions of the 1960s, through the current generation of arts for whom multi media and technology are the norm.

In the great tradition of the avant-garde the “9 Evenings” which were staged from October 13-23 in a cavernous New York armory with an average audience of 1,500 may be viewed as a magnificent triumph or a colossal flop. In a review reprinted in the catalog, Brian O’Doherty, was accurate and far more generous than his colleagues when he wrote that “…the impact of the affair has been enormous and its after-life, in film and still photos, begins to qualify and change what actually took place. These records tend to be more impressive imaginatively than the events themselves; the historical audience, seeking text book photos, will regret they were not there. The actual audience often regretted that they were.”

The experience of viewing this difficult, demanding and rewarding exhibition will be similar to the very responses that O’Doherty referred to so succinctly in his vintage text. There is the sense of elation for delving deeply into one of the true landmarks of contemporary art. The thrill of extracting rich nuggets of information and insight offset by the sense of tedious commitment to absorb such enervating videos, at best, just ghosts of performances that were tough to sit through during their original presentations. The major large screen video projection, for example, is a challenging two hour sit through of often really tedious material. There is a shorter, more accessible, better cut, twenty minute video that offers highlights and glimpses of all ten pieces.

Why bother you may well ask? Because the opportunity is too rare and important to be missed. This is that once in a lifetime invitation to revisit one of the true tipping points in contemporary art. It is the very notion of what was undertaken, the immensity and boldness of the challenge, that far outmeasures the very mixed actual outcome. The “9 Evenings” represent one of those great failures whose wreckage forms the beginning of what followed. If we learn from our mistakes then this was a Phoenix moment.

In the dinner that followed the opening several of the original artists and engineers offered their memories of the epic encounter between artists and engineers. Each knew little about the work and practice of the other. The key figure was the late Bill Kluver an engineer at Bell Laboratories. He had been working with artists to solve some of their technical problems and was the catalyst and founder of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Kluver was key in assembling an array of technicians and engineers to work with the artists. Initially they met and shared ideas. But it became apparent that they spoke in different modes and languages. Just how did an idea conveyed by a visual artist, musician or dancer, evolve into a form of communication that could be understood and resolved by an engineer using available technology.

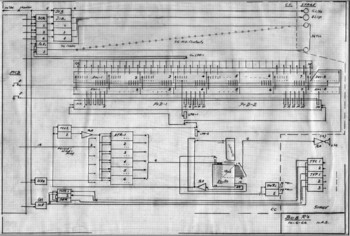

Eventually, Herb Schneider was brought into the project and his contribution proved to be crucial. He had meetings, several hours in length, with the ten individual artists- John Cage, composer, Lucinda Childs, dancer and choreographer, Oyvind Fahlstrom, painter and author of theatre pieces, Alex Hay, painter and choreographer, Deborah Hay, dancer and chorographer, Steve Paxton, dancer and choreographer, Yvonne Rainer, dancer and choreographer, Robert Rauschenberg, artist and choreographer, David Tudor, musician and composer, and Robert Whitman, film/video artist and author of theatre pieces- and then created one page diagrams which conveyed the essential information in a manner understood by engineers. From these they fabricated hot and cold circuit boards which were reconfigured for each individual event. Today, the set of drawings, the centerpiece of the exhibition, were loaned by Rauschenberg.

“I was not surprised by the ways the artists communicated,” Schneider said in an interview for the catalogue. “My job was to listen to their views and clarify their meaning. When things started the artists were in control and then months later nothing was working: they would throw ideas at the engineers, expecting them to turn around designs while the engineers were having a hard time pinpointing technical notions and their applications…The plug boards were the links between the external-the stage and audience areas-and the internal-the control area. They operated as a kind of computer, transferring information from one site to the other. Fixed items like lights were controlled from the plug boards, as was any equipment used by the participants. The diagrams illustrate those connections.”

As O’Doherty wrote “…part of one’s frequent anguish at the Armory was watching good ideas fail.” In another well measured review Lucy Lippard commented that the first night of performance served as a “dress rehearsal” for the second and only other performance. So there was a great deal of difference as to just what night one attended. Much of the technology, even relatively straight forward PA systems and slide/ film projections just didn’t function. Cage was frustrated that a volume control, key to his piece, failed. The irony is that so many of the ideas and technologies they struggled to work with pale by comparison to the pyrotechnics of today’s touring rock shows. Who knew that the primitive special effects of the avant-garde “9 Evenings,”some forty years ago, would morph into the halftime show of the Super Bowl.

As part of Rauschenberg’s “Open Score” there was a tennis match between suitably attired players, Mimi Kanarek and Frank Stella. Their rackets (the originals are displayed as artifacts in this exhibition) were rigged with sensors. As the ball was struck there was an amplified bing for her strokes and a bong for his. Each hit was also programmed to remotely extinguish one set of lights. Eventually the Armory was to be reduced to darkness. During the first night the remote system did not function and the engineers had to unplug the lights manually. Apparently it worked during the “better” repeat performance.

Which may also serve as a metaphor for this well intended but perhaps ultimately failed essay. It is challenging to write with compelling clarity about complex events presented to us second hand. But, given the degree of difficulty, even being there may not have made a great difference. Attending the actual events of history doesn’t automatically lead to greater understanding. Being there isn’t all that it is cracked up to be. Perhaps it serves quite as well to just “be” at the MIT exhibition in the presence of the artifacts. It is enough to behold and worship the relics of the avant-garde to receive their grace and indulgence. Ultimately the avant-garde is not about winning. Not making sense is ok when and if you pay your dues.