Isabel Huppert is Phaedra(s) at BAM

Triple Queen Seduces at the Harvey Theater

By: Susan Hall - Sep 18, 2016

Phaedra(s)

After Sarah Kane, Wajdi Mouawad and J. M. Coetzee

Directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski

Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe

Isabel Huppert (Aphrodite, Phaedra, Elizabeth Costello), Strophe (Agata Buzek), Andrze Cgyra (Hippolyte 2, Senior Lecturer), Alex Descas (Thesee, Doctor, Priest), Gaël Kailindi (Hippolyte 1), Norah Krief (OEnone), Rosalba Torres Guerro (Arab dancer), Grégoire Léauté (Musician).

Dramaturgy by Piotr Gruszczynski

Set and costume design by Malgorzata Szczesniak

Lighting design by Felice Ross

Music by Pawel Mykietyn

Video design by Denis Guéguin

Choreography by Claude Bardouil and Rosalba Torres Guerrero

Makeup, and hair design by Sylvie Cailler and Jocelyne Milazzo

Additional music composed by Bruno Helstroffer

Sound design by Thierry Jousse

Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theatre

New York, New York

September 17, 2016

Isabel Huppert captures Phaedra, a character who has fascinated through the ages. Racine best revealed her sense that neither lucidity nor sincerity is helpful in resolving emotional problems. Consciousness of failure is a noble human trait. This is Phaedra’s lesson. Phaedra knows but her knowledge is useless.

Looking at Euripides and Seneca, then translating Phaedra through contemporaries Sarah Kane, Wajdi Mouawad and J.M. Coetzee, Krzysztof Warlikowski dramatizes the tragic notion of impotence before the fates. The final take is uplifting, as a J. M. Coetzee character whizzes out into space, but then crashes.

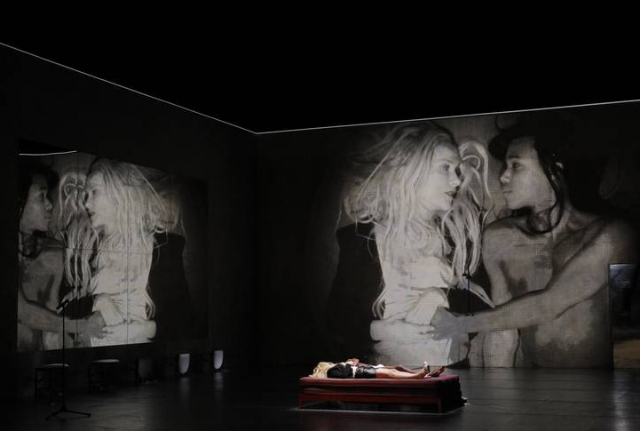

All the characters are broad and deep, but the setting is tight. Malgorzata Szczesniak has taken the full height and width of BAM’s Harvey stage and expanded it with mirrors and an open ceiling on which fans and lights become a tic, tac, toe board at times. The stage, lifted only about a foot, extends into the audience. At one moment, Hippolyte 2 steps off stage and sits in the first row of the orchestra in his contemporary incarnation.

Video images, often of the actors in distant action, bringing scenes close and repeating them to heighten the tension.

The story is bracketed and interwoven with the startling musicianship of Grégoire Léauté and the daring Arab dance of Rosalba Torres Guerro. Erotic sex and passion are everything as Guerro moves, sometimes with abrupt thrusts and often slithering up and down. The music by Pawel Mykietyn is driven, as we are, erotically.

The Hippolyte of myth is beautiful. Although he is Phaedra’s stepson, the two are not related by blood. At first played by sweet Gaël Kailindi the character seems innocent. As the play progresses, it is clear that incest is best, or at the very least thrilling.

In Phaedra’s encounter with her stepson, the incestuous part of the relationship makes it all the more exciting. Hippolyte's father is married to Phaedra who suggests that what she is doing is ok, because Hippolyte has given his own features to his father. An upstream genetic reverse?

An incomparable actress, Huppert plays Phaedra from her creation as the goddess Aphrodite to her humanization as Phaedra and on to Elizabeth Costello who describes among other things how the Gods think about us as much we think about them. Describing this interest, Costello sits with her crotch exposed for Godly examination?

As her own most ruthless critic, the brilliant Phaedra is in touch with her emotional, erotic base. Although Phaedra is in the process of dying or dead throughout the play, Huppert makes her lifeful. She knows the source of her power is Venus (the piece of Aphrodite which remains in her?). Passion. In a shocking, contemptuous moment, Hippolyte reports that Phaedra’s daughter considers him a more skilled lover than her husband. The revelation is a knife stab. The daughter's betrayal of the mother comes home to roost.

Hippolyte is descended from Jupiter and has his aggressive genes. In his room, a large glass playpen, which moves in and out of the stage with the action, he plays with a toy electric car and watches a loop of Janet Leigh’s shower murder on his television. There is a real shower in the middle of the rear stage wall throughout the evening, to both forecast and linger in Psycho.

Hippolyte transmits a not-so-childish STD to Phaedra. She in turn accuses him of rape to save herself from her husband’s wrath.

These heightened moments of cruelty and lust punctuate an evening in which the dying Phaedra is seducing her audience. Huppert can march about the set like a corporal, grind like a pole dancer and make poetry of language.

Perhaps royals, the group Phaedra belongs to, are always alienated and understand displacement better than the rest of us. Inbreeding has created hemophilia and perhaps the madness of King George III. Royals are not exempt. Phaedra understands this, yet she does not resist the trap. In fact, the family portrait ends up as a group of dead bodies.

Once a character has declared passion, there is no withdrawing from the game. Huppert plays it from her Godly birth to her contemporary demise as analyst. She gives us a brilliant evening of theatre.