Blanche Lazzell and the Color Woodcut

Provincetown's White Line Prints at the MFA

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 17, 2013

From Paris to Provincetown: Blanche Lazzell and the Color Woodcut

Curated by Barbara Stern Shapiro

Catalogue, 96 pages, MFA Publications, 2002

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

January 23 t0 April 29

Cleveland Museum of Art

May 19 to July 28

Elvehjem Museum of Art

University of Wisconsin, Madison

September 7 to November 3

With its expansive sand dunes, sublime beaches, and clear light the Outer Cape, the land’s end tip of Massachusetts seemingly stretching out a narrow extremity to Europe, Provincetown, and its neighboring waterfront villages, have long been a refuge to artists.

One of the first great figures of the still flourishing artists’ colony was the painter Charles W. Hawthorne (1872-1930). Students flocked to his summer landscape classes as he demonstrated his bravura, alla prima style of depicting the busy commercial activity of the now sadly diminished fishing fleet.

Immediately before and primarily during World War One, however, a new group of more progressive artists migrated to P’Town. This would establish a long standing dichotomy and aesthetic war between the traditional approach of Hawthorne and his disciple, another influential teacher, Henry Hensche (B. 1901), and the more progressive experimental artists led by Karl Knaths (1891-1971), Ross Moffett (1888-1971), and Edwin Dickinson (B.1891). In a later development, culminating in the summer long series of exhibitions, performances and seminars known as Forum ’49 (in 1949) there would be the further splintering of the emerging Abstract Expressionists, many of whom had come to study with Hans Hofmann (B. Germany 1880-1966). And, a generation after that, in the 1950s and 1960s, a group that showed at the famous Sun Gallery laid the foundation for Figurative Expressionism, Bob Thompson (1937-1966), Lester Johnson (B. 1919), and Jan Muller (B. Germany 1922-1958) as well as some of the earliest performance works of Red Grooms (B. 1937), Allan Kaprow (B. 1927) and Claes Oldenburg (B. Sweden, 1929).

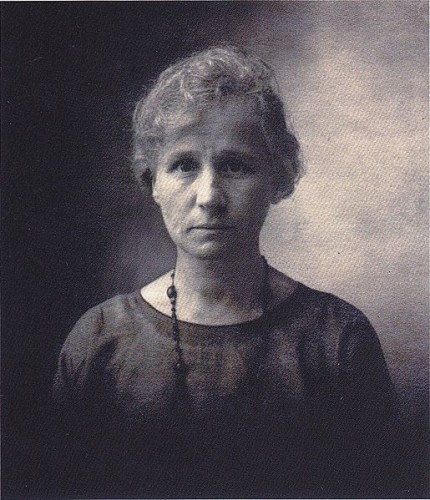

This stunning exhibition, focused on the White Line or Provincetown Prints of Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956), and her contemporaries, surveys the accomplishments of the generation which settled and continued to summer on the Cape during and after World War One. While she is now the most widely known of this group there are others who are as richly deserving of wider critical and scholarly attention. In that sense, it is a disservice to relegate them to the role of serving as a footnote to Lazzell, whose work has achieved a level of acceptance and value in the art market, while these other artists are more obscure. But, largely as a result of the seminal 1983 exhibition, curated by Janet Altic Flint, Provincetown Printers; A Woodcut Tradition, for the National Museum of American Art, and its now out of print catalogue, the market value of this work has risen sharply. And deservedly so.

It is also disappointing that this catalogue contains some footnotes, a detailed chronology, but no bibliography. The critical essay is adequate but primarily descriptive and brief. Accordingly, this exhibition and publication hardly invite further research and appreciation beyond a sketch of Lazzell and her work. One senses limited resources and commitment to this project on the part of the MFA. The exhibition appears to be the result primarily of access to a rich trove of material collected by Leslie and Johanna Garfield, including many prints, and some of the original wood blocks. Significantly, they purchased their first Provincetown Print in 1984 shortly after Flint’s exhibition. I have also seen an abundance of this material in the collection of the late Reggie Cabral and other Provincetown collections.

What is particularly interesting in the group exhibition that serves as a kind of ante chamber to the Lazzell galleries is the large representation of women artists. A number of these women, including several lesbians who had been a part of the circle of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, had left Paris because of the war. With its open acceptance of alternative sexuality it is understandable that gays and lesbians found a supportive and quasi European environment in the no questions asked, Portuguese fishing community.

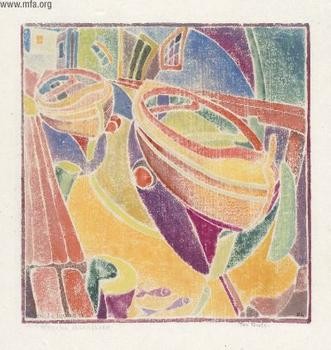

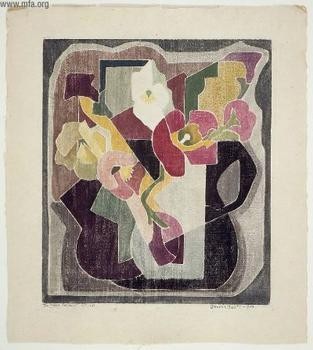

The artists imported from Europe the latest style of the Fauve and Cubism. One sees this clearly in the clean, rich, high chroma color and the penchant for flatness, a quality inherent in the wood block. Lazzell, particularly at mid career, pursued the geometry and fracturing of cubism. This is not, however, the radical Cubism of Picasso and Braque, but rather, what John Richardson has coined, the Salon Cubists, including Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, the authors of the 1912 self-help manual, Du Cubism. Also, Gleizes gave lessons. And, one assumes, those well heeled Americans, particularly women, oh how they loved to take lessons.

So, in the Provincetown painters and printmakers one sees a prominent strain of a decorative and more illustrative form of Cubism. Nature reduced less to the cube, cone and cylinder of Cezanne, than to the stained glass daubs of light surrounded by confining outlines that one is familiar with in the ersatz Cubism of Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928).

Karl Knaths, for example, who worked with Cubist concepts throughout his career, bending and shaping it to his own unique and inventive manner, never traveled to Europe, but drank of the cup of modernism through his sister in law, the brilliant artist, Agnes Weinrich (died 1946), whose originality is only now coming to light. The sisters Weinrich, Agnes and Helen, a pianist, had just returned from Europe.

The White Line or Provincetown Print is credited to Bror Julius Olsson (B.J.O.) Nordfeldt. Using broad lines cut into an unaltered wood plane, it was a manner of painting or hand inking a single block. It was labor intensive to ink the single block for printing but less complex than the traditional method is using multiple blocks, one for each color, through multiple registered printings, to create a complex color print. It has been suggested that he may have been aware and influenced by the Edvard Munch technique of cutting a single block like a jig saw puzzle, inking each segment, reassembling and then rubbing a single impression. The technique was quickly taken up by others in the P’Town community and Lazzell, who died at seventy-seven in 1956, continued to produce these woodblock prints, as well as painting, rugs and crafts, throughout her career.

The greatest strength of this exhibition is the opportunity to study several of the original blocks and preliminary studies as well as quite different inking and printing of the blocks. Like the technique of monotype the artist is free to make endless variations and inventions so no two prints strive to be consistent. In that sense each print is an unique object.

Lazzell seems to be at her best depicting the small houses and narrow streets with their views of the ocean beyond that make Provincetown so charming and unique. She abstracts this clutter of houses into a delightful array of Fauve inspired color and Cubist fracturing. There are also still life works where she appears to push the limits further to a kind of Synthetic Cubism. Significantly, she later studied with Hofmann and knew well his concept of Push Pull delivered in a thick German accent. But while many others seemed to be dominated by Hofmann, or Hensche for that matter, Lazzell seemed to draw on new ideas while remaining focused on her own ideas and vision.

While the presentation of work by Lazzell gives a broad account of her oeuvre there is so much more that one wants to know about her peers and contemporaries. This exhibition includes: Gustave Baumann (B. Germany, 1881-1971), Ada Gilmore Chaffee (1883-1955), Mabel Hewit, (1903-1987), Edna Boies Hopkins (1872-1937), Ethel Mars (1876-1959), Mildred “Dolly” McMillen (1884-about 1940), B.J.O. Nordfeldt (B. Sweden, 1878-1955), Maude Hunt Squire, (1873-1954), and Grace Martin (Frame) Taylor, (1903-1995).

And, it is unfortunate that the early monotypes of Knaths, circa. 1913-14, with their dramatic abstraction, were not included. He also made Provincetown Prints and was a clear influence on these artists. I have seen these remarkable monotypes, in an abstract, non Cubist manner (that would evolved later in his work), more reminiscent of early Kandinsky or Kupka, signed Otto and later Karl Knaths, in the collections of Jim and Jean Young and the late Nat Halper. They reveal that he was the most advanced modernist in P’Town, and among the American avant-garde elite, at that time. And the works of Weinrich belong here as well as Ferol Warthern who continued to make Provincetown Prints into the 1980s.

Basically, I find the work of all of these artists of great interest and worthy of future intensive study and the subject for further exhibitions.

The prints of Squire, while less radical and abstract, are superb Fauve flavored genre scenes with a delicate and sure sense of color and surface. The genre prints of Nordfeldt, an artist who deserved to be seen depth, is represented here by five rough and expressionist (perhaps a reflection of his European origin) genre prints and one block. McMillen confined herself to just black and white but her images have a crisp graphic style. They remind one of Rockwell Kent but I am not implying a direct connection. The prints of Mars are utterly charming. There is a back yard view of two women tending to a garden, while in another, couples are dancing and dining at an outdoor café. She printed in a broad, splashy even painterly style. The prints by Baumann stand apart. They are both more technically accomplished as well as severe and dispassionate. This is evidence of a well trained but more academic and less creative artist. But they make an interesting bookend to the more loose and experimental images of some of the other artists.

The frustration of this show is that it makes one hunger for more. Not more Lazzell. This will do nicely thank you.

You sense that this show was intended to be a splash of color, a spring bouquet, to complement the rich visual feast of French Impressionist Still Life the current main event at the MFA. But this show should have been more than just a little confection to delight the eye of the causal visitor and impressionist tourist. There is a great and important story of early modernism on Cape Cod that still remains to be researched and presented. It is one of the greatest unwritten chapters in the colorful history of American art and the epic struggles of modernism.

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine March 3, 2002.

-----