Cambodia: Part One

Phnom Penh

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 17, 2010

Our covered speedboat with panoramic windows took us to the border, to clear Vietnamese and Cambodian passport controls, which are a short distance from one another. Each check-point took thirty minutes to clear, giving us an opportunity to browse through souvenir shops while we waited. Vietnamese ingenuity stood out with a fan which became a sun hat by joining the two velcro ends. The Cambodian shop was impressive with its elegant handicrafts, whetting our appetite for what was to come.

On our boat with the national flag swaying in the breeze, we traveled upriver to Phnom Penh, passing villages with houses on stilts, skylines with pagodas and cranes for new construction, and shores fringed with fish nets and boats. At the dock, Thaly, our Cambodian guide, welcomed us with a big smile. It was 40 degrees C, not unusual for Cambodia, which is hot year round.

Riding to the Almond Hotel, our home for two nights, we saw signs of the past glories and defeats of the city. The attractive riverside capital’s broad boulevards, named after kings, had taken on a shabby, run-down appearance due to long years of war and abandonment by the Khmer Rouge. Hope, though, was in the air; new hotels and restaurants lined the riverside. We drove by the lotus-shaped Independence Monument, built in 1953 to celebrate the nation’s freedom from France, which colonized Cambodia for ninety years starting in 1863.

Following a Cantonese lunch at the hotel, we visited the Royal Palace, located near the intersection of four rivers: the upper Mekong, the Tonle Sap, the lower Mekong, and the Tonle Basac. Built in 1866 in traditional Khmer style, with tiered roofs and topped by towers symbolizing prosperity, it has served as the official residence of King Norodom Sihanouk, the survivor of the constitutional monarchy, since his return to the capital in 1992. The residential quarter of the former king is not open to the general public; neither is the Royal Residence Compound of the current King, Norodom Sihamoni.

Dominating the center of the larger, northern section of the Royal Compound is the Royal Throne Hall, used for coronations, major constitutional events, and the acceptance of ambassadorial credentials. The interior walls of the Hall are painted with scenes from the Reamker, the Khmer version of the Ramayana.

Near the North Gate is Wat Preah Keo, or the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, which is also known as the Silver Pagoda because of its 5000 silver floor tiles, weighing more than one kilogram each. Disappointingly, all but a small corner of the floor is covered by a protective thick carpet, obstructing its grandeur. The temple, which has an ornately carved exterior, houses two priceless Buddha figures: the 17th-century Emerald Buddha, made of crystal, and the 90-kilogram pure Gold Buddha, encrusted with diamonds, the largest of which is 25 karats. The temple is considered to house the sacred symbol of the nation; therefore, photography within the building is forbidden.

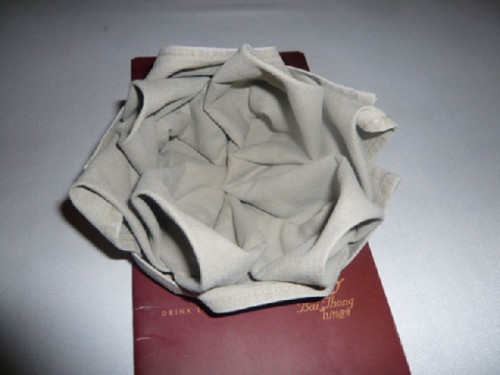

Dinner was an elegant affair at a Thai restaurant. A white napkin folded like a flower over the menu identified each place setting. The presentation of the set five-course menu appealed to both the eye and the taste buds. The royal elegance of the palace lingered in many of the city’s restaurants, hotels, and shops.

The next morning’s trip to the Genocide Museum was a heart-wrenching experience, yet a must for all visitors to understand the extent of crimes inflicted on the graceful people of this gentle land. The former prison, known as “S 21” (Security Office 21), was the largest of 167 prisons created on the orders of Pol Pot. Once a school, the building was converted into a prison surrounded by double walls and surmounted by dense barbed wires. The classrooms were made into cells. Around 20,000 people perceived as supporters of the former regime, or Khmer Rouge officials who had fallen from grace, were interrogated here under torture and subsequently murdered with their families.

The museum was opened in 1979 to show the evidence collected for the Tribunal prosecuting the criminal leaders. Among the exhibits are photographs, films, prisoner confession archives, torture tools, a list of prisoners, as well as their clothes and belongings. The bodies of fourteen victims, one female, believed to be the last killed before the regime fell, are buried in the museum grounds. The museum’s brochure states that “Keeping the memory of the atrocities committed on Cambodian soil alive is the key to building a new, strong and just state.”

A stupa-shaped mausoleum has been erected in memory of the victims in the Killing Fields, seven miles south of the town. On the way, we passed by slash-and-burn farms, fields of morning glory grown as cow feed, and houses with cows tied up front amidst trash. Even modern buildings alternated with junkyards; produce vendors spread their goods over a piece of cloth on the sidewalk, while police with mouth masks managed traffic. The river was the source of daily water until two years ago; with NGO and Japanese government help, running water now reaches all houses.

The Killing Fields are one of over nine thousand mass graves discovered to date where prisoners were executed and buried. Many of these graves have now been exhumed; row upon row of skulls are arranged in tiers in a tall plexi-glass case in the middle of the mausoleum. Hundreds of folded origami paper cranes left by the Japanese Red Cross adorn the entrance. Bones and clothes are displayed separately in free-standing cases on the grounds.

As we walked about, we came upon a few tombstones with Chinese characters, indicating that this was formerly a Chinese cemetery. Chickens roamed about, pecking for food in the ground and unearthing an occasional human bone in the process. The estimated number of people who died from execution, forced hardships, or starvation during the Khmer Rouge regime under Pol Pot from 1975 to 1979 is 1.5 million. Vietnamese troops invaded in 1979 and drove the Khmer Rouge to the countryside, beginning a ten-year occupation. The 1991 Paris Peace Accords mandated a ceasefire and democratic elections. A coalition government was formed; the constitutional monarchy, along with the palace, survived.

Phnom Penh has several large markets. We visited Psar Toul Tom Pong, also known as the Russian Market. The name refers to the time from 1979 to 1993, when Russians, along with Vietnamese, were in the country and enjoyed shopping here. The market has several wings lined by hundreds of small shops, which are crammed with anything locals might need: clothing, bags, jewelry, silk, curios, souvenirs, and a wide variety of dried and fresh food. Tailors measure and sew outfits quickly or do repairs while people shop.

At one time Khmer silk was considered to be one of the most intricate and delicate in Asia. This once prosperous occupation was, however, destroyed during the Khmer Rouge period. Fortunately, silk farming and weaving have recently undergone a revival. New designs, combined with traditional workmanship and inspired by ancient patterns, are now coming onto the market.

Behind a small public garden is the National Museum, which is housed in a red pavilion built in 1918. The museum is prized for its impressive collection of some 5,000 objects of Khmer art, some made from stone said to be the finest in existence, though none may be photographed. The exhibits include a 6th-century statue of Vishnu, a 9th-century statue of Shiva, and a damaged bust of a reclining Vishnu, which was once part of a massive bronze statue found in Angkor Wat.

In the evening we enjoyed a sunset cruise on the river. The captain’s wife and daughter accompanied us on the boat. As the sun went down, pagodas silhouetted the shoreline, while lights came on randomly on other buildings. Afterwards, we paired up for a ride along the boardwalk and through the town in a rickshaw, called a remok. The night view of Phnom Penh accentuated its monuments. Lit up against the night sky, the Lady Penh Monument paid tribute to the city’s namesake, as Phnom Penh means “City of Lady Penh,” an early benefactor.

Delivered by remok to a nearby restaurant, our buffet dinner was an overwhelming array of Asian foods, which ranged from grilled prawns and fresh salads to more exotic fare, such as stir-fried morning glory stems. The place buzzed with activity, as tourists and locals moved among the many stations crowded with foods alien to the unaccustomed eye. The spread included a variety of beef, pork, chicken, duck, fish, and soup dishes. In Cambodia soup is served as an accompaniment to main courses, not before them as in the West. There are three Cambodian restaurants in and around Boston, run by a couple who were forced into exile by the Khmer Rouge takeover. They have also produced The Elephant Walk Cookbook, an adventure into Cambodian cookery.

On the way back to our hotel we passed by a Kentucky Fried Chicken making its mark with prominently-lit signs in this city, which appears to be racing into a market economy. Based on my observations of speedy development in Phnom Penh, I looked forward to the next leg of our trip, to Siem Reap, which I had visited five years earlier. Would I recognize the city?