"The Ouroboros Trilogy" at ArtsEmerson

Three Operas on Ancient Myths by Brookline Librettist

By: David Bonetti - Sep 12, 2016

Ouroboros Trilogy

Creator and Librettist: Cerise Lim Jacobs

Producer: Beth Morrison Projects

Executive Producer: Friends of Madame White Snake

Production Team: Director and Production Designer; Michael Counts; Video and Projections Designer: S. Katy Tucker; Costume Designer: Zane Pihlstrom; Lighting Designer: Yi Zhao; Dramaturg: Cori Ellison

Creative Team:

“Naga”

Composer: Scott Wheeler

Conductor: Carolyn Kuan

Cast: Matthew Worth (Monk); Sandra Piques Eddy (Wife); David Salsbery Fry (Master); Stacey Tappan (Madame White Snake); Anthony Roth Costanzo (Xiao Qing)

“Madame White Snake”

Composer: Zhou Long

Conductor: Lan Shui

Cast: Susannah Biller (Madame White Snake); Michael Maniaci (Xiao Qing); Peter Tantsits (Xu Xian); Dong-Jian Gong (Abbot Fahai)

“Gilgamesh”

Composer: Paola Prestini

Conductor: Julian Wachner

Cast: Christopher Burchett (Ming/Gilgamesh); Heather Buck (Ku); Hila Plitmann (Madame White Snake); Anthony Roth Costanzo (Xiao Qing); Andrew Nolen (Abbot Fahai)

An unnamed orchestra and chorus and the Boston Children’s Chorus

ArtsEmerson, Emerson College/Cutler Majestic Theatre

Sept. 10 to 17

"The Ouroboros Trilogy" had so many hands involved in its making – ArtsEmerson, Beth Morrison Productions, the Friends of Madame White Snake, “creator and librettist” Cerise Lim Jacobs, three different composers, three different conductors, three different casts – that I feared it might collapse under its own weight into chaos.

Not to worry. The Trilogy of two world premieres and a reprise of a work premiered in 2010, which I saw in a marathon Saturday session that lasted from 11 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. (with two generous breaks), was a triumph, even if there were a few problems. (Like when is there not when opera is brought live to the stage?) Despite there being some plot repetitions from work to work and three different musical styles employed, the trilogy as a whole works as a unified statement. Each roughly 100-minute long opera is written to stand on its own, but seeing all three – at once or over a period of time – only enhances the experience, I suspect, giving the audience a deeper appreciation of the themes addressed.

The Trilogy, which is the creation in every sense of the word of Brookline resident Cerise Lim Jacobs, who was a long-time trial lawyer in a high-powered local law firm, has been many years in the making. Appropriately featuring creation myths from several ancient cultures, it uses the ouroboros myth of Greek legend, the story of the snake that swallows itself, being reborn in the process, as a recurring, structuring motif. One opera from the Trilogy, “Madame White Snake,” was premiered in 2010 under the auspices of the defunct Opera Boston; it won the Pulitzer Prize for music in 2011.

Even if it had been a failure, which I repeat, it decidedly was not, the Trilogy would have counted as the most ambitious opera undertaking Boston has ever seen. Not that the city has been unambitious in terms operatic, even if those ambitions were not always sustained. Those with gray hairs can remember the fatal ambitions of Sarah Caldwell and her legendary company, which featured many world premieres and the American premieres of Berlioz’s “Les Troyens,” Prokofiev’s “War and Peace,” Schoenberg’s “Moses and Aron” and the original French version of Verdi’s “Don Carlos,” among others - many of which exceeded four-hour length. And in recent years, the Boston Early Music Festival has exhumed operas long forgotten in European archives; it mounted its own trilogy, of Monteverdi’s three surviving operas, just last year – however, those operas, which date among the earliest in the repertory, were not premieres.

So what does it take to mount a trilogy of operas, two of which are world premieres? It takes a lot of moxie, which Jacobs seems to have in unlimited quantity, and it takes a lot of money, which Jacobs seems also to enjoy. That is, of course, a formula for a vanity project, which Boston also has some experience with in the opera field. But the best way of answering charges of vanity is to do what you’re doing better than the competition. And that is just what Jacobs has done. She engaged outstanding composers, fine conductors, a talented cast and a superb production team to realize her vision.

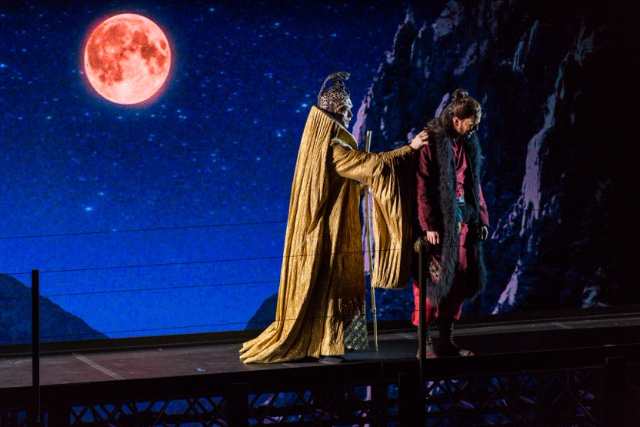

Indeed, it is the production team (overseen by production designer Michael Counts) that proves the glue that ties the three works together, as much as, maybe even more than, their overlapping stories and the two recurrent central characters, Madame White Snake and her bestie, Xiao Qing. From the very first moments of the very first scene of “Naga,” the trilogy’s opening work, the production team made its mark powerfully felt. As the minimalist-oriented overture (by Scott Wheeler) plays, we see against an indigo sky a boat move very slowly from upper stage right across the stage on a diagonal. In it are two fantastically garbed creatures (costumes by Zane Pihlstrom), bathed in moonlight (lighting by Yi Zhao). They turn out to be Madame White Snake, who wears a white gown with elaborate headwear, a bifurcated (to represent her tongue?) white hat with a chain of red blossoms dangling below her neck, and Xiao Qing, whose green gown (and enormous trailing tail) is made fully evident in subsequent scenes. The effect is magical, time seeming to stop as these two exotic creatures take center stage, a world we are privileged to witness, if not join. It was one of the most beautiful openings to an opera I’ve seen in Boston – anywhere, for that matter – and the gorgeous stage visuals continue through all three operas to their very last moment.

In subsequent scenes, the video projections by S. Katy Tucker come to define the production’s style and look. We live in the age of media, yet opera, theater in general, is shy in its embrace – no wonder the younger generation stays away from anything on the stage. Tucker’s work for the Trilogy is technologically advanced, making traditional sets unnecessary, and when projections change seamlessly from second to second, as they do when the seasons change and flowering trees drop their blossoms in “Madame White Snake,” the effect is astonishing, breathtaking. I’ve seen successful video projections before, in the old New York City Opera’s production of Rossini’s “Moses in Egypt,” for instance, which Counts also produced, but none ever this effective. Raging waters, a slithering computer-generated white snake, deep mountain gorges, snow, showers of pink flower blossoms all appear and disappear in the blink of an eye.

Another glue that ties the works together into more than a sum of its three parts is, of course, Jacobs’s libretti. Steeped in myth, primarily Asian, specifically Chinese (although the central image of the Ouroboros is Greek and the memory of the Flood seems to be universal) the stories are stripped to essentials with fanciful elaborations – the Monk and his Wife in “Naga,” for instance – added to facilitate human connection. This is a myth-based work that resides comfortably on the Earth – the heavenly creatures come down to it if they don’t already live there among humans. (And what god could be a more earthbound than a demon snake?)

Jacobs’s libretti are prosaic – to their advantage. They don’t get caught up in highfalutin’ poetic vocabulary and metaphor. They tell their tales succinctly. She seems to understand that operas that last shy of two hours, like those of the Trilogy, are more endurable – and pleasurable - for the restless contemporary audience than ones that are bloated with self-conscious versification. Jacobs might have stifled whatever poetic inclinations she might have, if she indeed has any, but she did so with the audience in mind. Her texts are easily absorbed, by the ear as well as read on the projected titles. She has written familiar forms such as ballads and lullabies, giving the composers opportunities to compose what in traditional opera are called “arias.”

Jacobs chose three composers of different backgrounds and aesthetics, yet ones who play well together. The one who sets the tone for the Trilogy is Chinese-American composer Zhou Long, who composed the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Madame White Snake,” which was produced second Saturday afternoon. Lang’s vocabulary is modernist – there are spiky notes, dissonances and the sliding, scooping vocal lines of the Second Viennese School – but he also uses the Chinese traditions in which he was steeped. The orchestra, which is basically western in composition, includes Chinese instruments such as the Chinese flute and the erhu, and Long’s Madame White Snake sings in the high, tight, vibratoless style of Peking opera. Long’s skill is that he welds both traditions together seamlessly, creating a new sound world we’d like to hear more of.

Scott Wheeler, who wrote “Naga,” is a Bostonian who has a reputation for edgy sounds, but he patterned his opera on more traditional precedents. True, there are plonks and tweets enough in his orchestrations to keep his experimental credentials intact, but the work embraces a warm romanticism in its sweep, reminiscent from time to time of Aaron Copland, Benjamin Britten and even Puccini, although never derivative of any of them. There is also a wonderful little reference to John Adams’s “Nixon in China,” in which Xiao Qing spits out the words, “rats, rats, rats” like Nixon did in his hotel bedroom – in Beijing – in his paranoia-steeped aria, “The rats will eat the sheets.”

Paola Prestini opened “Gilgamesh,” the Trilogy’s final work, with an extended overture that sounded like prestige-film music. She soon shifted to a more standard contemporary opera style composition, with the inevitable debts to Philip Glass. Indeed, all three composers resorted to writing passages of Glassian minimalism, which is inescapable in contemporary American opera – maybe because it tends to work.

The plots of the operas are way too complicated to reprise here – in fact, I don’t think I could if I had to. But all three works feature two characters, Madame White Snake, who is variously divine or human, and her servant, Xiao Qing, who as a man was in love with her but was transformed into a female green snake so that he could accompany her. In the works

White Snake becomes human so she can experience love, giving birth to the half god, half human Ming, whose human wife gives birth to another human/divine hybrid in something of a Rosemary’s Baby episode. Along the way there are virile human lovers and perfidious masters and abbots. But in the end, it all starts over again, like the Ouroboros the Trilogy is named for.

For the most part, the cast was superb. At the Trilogy’s center is Madame White Snake, who was sung by three different sopranos. In “Naga,” Stacey Tappan found the role’s high tessitura an uncomfortable stretch, turning to shrieking to hit her high notes. In “Madame White Snake,” Susannah Biller created a portrait of the divine snake become human in her quest for love as a distanced figure, her high, vibrato-less singing a perfect evocation of the stylized highly formal singing of the Beijing opera. She hit every note at its center and her voice, within the limits of the style required, was warm and full. In “Gilgamesh,” Hila Plitmann, again a more down-to-earth singer of the Western tradition like her predecessor in “Naga,” also had trouble with the high tessitura, but she negotiated it better.

Xiao Qing, the loyal side-kick with the enormous green tail, was sung by two countertenors, luckily for the audience two of the best countertenors on the American stage today. Michael Maniaci, who was heard locally last season in Mozart’s “Lucio Silla,” reprised his role from the 2010 production of “Lady White Snake.” A stolid figure, he barely moved and when he did he did so at a stately pace. His movement was reminiscent of classic Robert Wilson direction, and his affect was reminiscent of the Wilson favorite, Jessye Norman. And Maniaci sang with style and beauty of tone. Unfortunately for him, however, he shared the role of Xiao Qing with Anthony Roth Costanzo, one of the most exciting young singers of any vocal category in the United States. (I saw him last year at the San Francisco Opera in Handel’s “Partenope,” and he stole the show from its star-studded cast with his peerless singing and acrobatic acting.) His Xiao Qing was more active, more alive than Maniaci’s, and his vocalism was textbook perfect, marrying clear enunciation with tonal beauty. In “Gilgamesh,” however, Prestini wrote a role that caused him to go into a baritonial range, and there was a gap between his two voices. Not his fault, but the composer’s.

“Naga” had a lovely scene between a Monk who is leaving his Wife of ten years to return to his Master. Baritone Matthew Worth pleaded audience indulgence because of a cold, but he turned in an affective, manly performance. As his wife, mezzo-soprano Sandra Piques Eddy delivered an equally moving performance even though there was a slight warble to her voice.

In “Madame White Snake,” Peter Tantsits sang the role of Xu Xian, White Snake’s human lover and father to her son, with assurance. His voice type is listed as “high tenor,” which is as it describes, high but not countertenor high. His inclusion and the heavy representation of female voices and male countertenors gave all three operas a high-lying sound profile, which is appropriate perhaps to its basis in myth.

And it also makes the few low-lying male voices sound special by exception. In “Gilgamesh,” the role of Ming, the half god/half human son of White Snake and Xu Xian, was sung very effectively by baritone Christopher Burchett. His wife Ku, who seemed clueless about his divided nature, and who gives birth at the end of the opera to a baby who is taken away from her, was sung by soprano Heather Buck, who put in one of the best performances of the entire Trilogy.

All three male voices singing Abbots and Master were fine.

All three conductors turned in committed performances as did the indefatigable orchestra. Outstanding was the choral work done by an unnamed adult chorus and the Boston Children’s Chorus.

If I seem to have run out of steam toward the end here, it might have been because I ran out of steam at the Cutler Majestic during “Gilgamesh,” the final opera in the Trilogy. That might have been because of my own energy level, but I think it might have had something to do with the fact that “Gilgamesh” was the least coherent of the works. It began with a lengthy repetition of what had gone on before and it was marred by a more disparate text, with Jacobs throwing in large blocks of text from Shakespeare and others. Maybe it was the text, but Prestini also seemed to be somewhat lost in the work, especially compared with Wheeler and Long.

Still “Gilgamesh,” could be improved with a little work – although Jacobs who reportedly has five new works in the pipeline, one “Rev.23,” based on the Book of Revelations, with music by Julian Wachner, the conductor for “Gilgamesh,” is scheduled for next season here in Boston, probably prefers to push forward not look back.

All things considered, the Ouroboros Trilogy has contributed one major work to the repertory, Zhou Long’s “Madame White Snake” – and one wonders why other companies have not taken it up – and two honorable pieces to accompany it. It will be a long time, I suspect, before Boston audiences encounter anything else so ambitious.