How George Seybolt Changed the MFA

Board President Initiated Business Concepts from 1968 to 1972

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 11, 2020

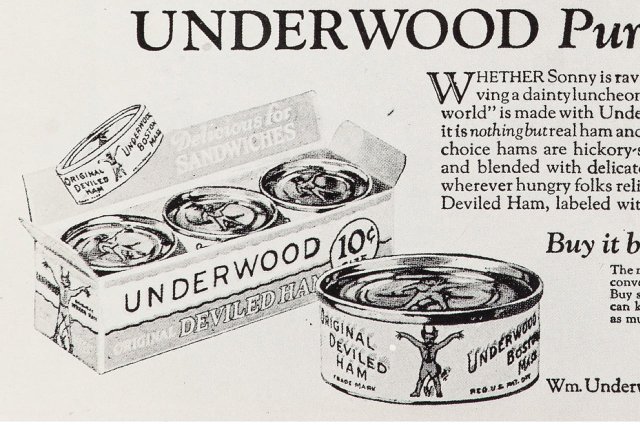

George Crossan Seybolt, (1915-1993) was president and chairman of the William Underwood Company, best known for its canned Deviled Ham. Raised in Hannibal, Missouri he dramatically changed the tone and mandate of the primarily legacy/ Brahmin board of the Museum of Fine Arts which he joined in 1968.

He was recruited by director Perry T. Rathbone who he was then instrumental in ousting. That resulted from a bungled attempt to smuggle from Italy a small portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga alleged to be by Raphael “Portrait of a Young Girl,” 1505. The acquisition for some $800,000 was to have been the highlight of the museum’s centennial celebrations in 1970. The painting, which was eventually returned to Italy, was published in the centennial catalogue.

The incident is the subject of the book “The Boston Raphael: A Mysterious Painting, an Embattled Museum in an Era of Change and a Daughter’s Search for Truth” by Belinda Rathbone. She tracked down the painting to the Uffizi Museum in Florence where it languishes in storage.

The author argues that the incident might have been handled with diplomacy. The ouster was extreme and may have been the opportunity Seybolt seized upon to initiate a broad agenda for change. These were articulated in an Ad Hoc Policy Report created when he was President of the Board of Trustees.

When Rathbone resigned in 1972, there was a transitional year with classical curator, Cornelius Vermeule as Acting Director. A list of potential directors, including the architect I. M. Pei, was initiated. Given the turmoil of the museum at that time it was alleged that top candidates were not anxious to assume the position.

Acting preemptively, Seybolt offered the position to Merrill Rueppel, a relatively unknown museum professional then director of a small museum in Texas. Seybolt stepped down from the board and was replaced by former Fogg Art Museum director, John Coolidge. There was turmoil that resulted when Rueppel attempted to initiate the Ad Hoc directives. Internal conflicts with curators and staff were leaked to the Boston Globe. Investigative reporting led to Rueppel being fired. Coolidge also stepped down and was replaced by former MIT President, Howard Johnson. The Asiatic curator, Jan Fontein became Acting Director, then a year later Director.

When Johnson and Fontein got the museum back on track some of the initiatives of the Ad Hoc report were followed. They included climate control renovation, construction of Pei’s West Wing, support for a contemporary art program, and the appointment of a curator of painting. Broader mandates for diversity and community access were given token response. That tepid action culminated in accusations of racism that the museum has faced and responded to during a time of crisis conflating the Black Lives Matter movement and Covid shutdown.

Essentially, Seybolt attempted to run the museum as a business. Toward that end he demanded an office and two secretaries. He barraged Rathbone with daily memos and expanded the role and authority of the President as at least equal to that of the Director. During the Centennial he chaired the museum’s first capital campaign. At the time, the museum’s endowment was half that of the Metropolitan Museum. While ranked second for its collections the museum was relatively poor. Decades would follow of renovation, expansion, acquisitions and blockbuster exhibitions.

While Rathbone initiated many changes, he represented a transition from an elitist institution to one representing expansion and transparency. Since 1972, there has been a change from the old Brahmin museum, to one that represents and reaches out to all of the people and neighborhoods of the diverse city of Boston.

In 1974 Seybolt became President Emeritus of the museum. In 1980 he retired from Underwood. Expanding on his work with the MFA he became a lobbyist and visionary for museums. President Jimmy Carter appointed him the first chairman of the National Museum Services Board, an advisory group, and he was a founder of the Museum Trustees Association in Washington. That was the focus of our discussion in May, 1977.

Charles Giuliano What is the status of your appointment to the Institute of Museum Services?

(IMLS was established by the Museum and Library Services Act (MLSA) on September 30, 1996, which includes the Library Services and Technology Act and the Museum Services Act. This act was reauthorized in 2003 and again in 2010. The law combined the Institute of Museum Services, which had been in existence since 1976, and the Library Programs Office, which had been part of the Department of Education since 1956. Lawmakers at that time saw "great potential in an Institute that is focused on the combined roles that libraries and museums play in our community life.")

George Seybolt The legal position is that the President nominates a board of fifteen. The Senate committee provides advice and consent. The President then nominates a chairman. So, it’s a long way from an accomplished fact. I have not been pressing it. My position is that they ask if you will serve and you say yes. It takes time. Based on everything that I have seen, I suspect that if the administration was established it would have been done a long time ago.

CG It seems the Carter administration is still getting settled.

GS It’s dealing with something that’s just been created. Here is a whole new thing so it is much harder than filling existing positions. I haven’t met President Carter. He takes recommendations but it’s his decision.

CG Is this under HEW?

GS This is a separate organization.

CG Where does Califano fit in? (Joseph Anthony Califano Jr. is a former United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare.)

GS He’s enthusiastic about it. He sees art and education as parallel and I think he’s right about that.

CG The Washington Post has reported that Califano has been dragging his feet about this.

GS A new budget for IMS starts on October 1 with $3 million. Both House and Senate have recommended it. But they have differences so they need to meet and come to a compromise. The total authorized for the first year was $15 million. When Congress creates a piece of legislation, particularly expenditure legislation, they put a ceiling on the authorization. They authorize it for three years. The ceiling for 1976, which starts on October 1, is $15 million.

This bill was created a year ago and went through both Houses and President Ford signed it. He made no recommendation for funding. He was less than enthusiastic. Our best friends were Democrats in Congress; Pell, Javitz and Brademas. It went through with the highest vote for any arts legislation that has been passed.

When Mr. Califano came in and had to go to the Office of Management and Budget (run by Bert Lance, a Georgia businessman, who resigned in his first year because of a scandal from which he was later cleared) he and the White House group said OK and authorized $ 3 Million. It was the White House saying we just want to spend $ 3 million on this and see how it goes.

CG Why is the administration being slow to appoint a director?

GS I have had no contact with the White House. I have met Mrs. Mondale and she is a great friend of the arts. I don’t know anyone else on the staff. The recommendation from Califano’s office has only been in the past few days. They have their own routines for doing these things. Whoever the President hands this to, and I haven’t the slightest idea of who that might be, will discuss it with him if he has any interest in it. I really don’t know where it centers over there. Five or six people in different capacities look at it and then he sends it down as his appointment. When he does that, I don’t know. I haven’t chased it.

CG Why do we need the IMS? How is it different from the National Endowments?

GS I was a member of the Endowment council for three years so I am in a good position to answer that. The Endowment is project oriented. It is supposed to take care of specific and particular one-time needs. These may be defined as a catalogue for an exhibition, or it may be six catalogues, but they are specific and separate things.

CG How is that defined in the charter and bylaws?

GS It is and embedded in its policy. There are exceptions to this. For instance, symphony orchestras, if they are a certain size, are given a certain amount of money each year. There are other things the Endowment does that are voted on every year. They have some uncertainty but are accepted and that’s expected every year. As far as museums are concerned in the Endowments, they were never envisioned as being included. When Roger Stevens and Livingston Biddle invented it, and wrote the legislation to a large part, and Biddle was Deputy Director under Stevens. Today, Stevens runs the Kennedy Center. He’s a business man who made a lot of money in construction. He became interested in the arts and became a producer and a backer. He got into this and helped to promote the Endowments particularly the Arts Endowment. He served as the first Chairman there and there have only been two, Stevens and Hanks. He’s a producer and financier at the Kennedy Center. When Roger conceived of the Foundations his only interest was in the performing arts. It wasn’t until he retired, and Nancy Hanks came in eight years ago, that there was any museum program at all.

CG Didn’t Brademas have a role in bringing about that program?

GS Claiborne Pell and John Brademas introduced legislation similar to the IMS. It was not the same but had a similar principle. Perhaps the reaction was that it was a rival and could be taken care of in the Endowments. When that program was first brought in it was about $1 million. It was for project work, perhaps a catalogue, but not for brick and mortar. It was not for purchases and endowment but for operating things related to projects. Perhaps a study of air conditioning and climate control, or the restoration of some paintings. Perhaps funding a sabbatical for a curator.

CG What about the MFA’s $2 million grant for climate control from the NEA? Isn’t that bricks and mortar?

GS That came later. They went around the country and found that in the older museums like Philadelphia, Boston and Chicago, that they never provided for climate control. The NEA set up one-time grants for that purpose. They tried to clear them all up and to give all those museums a turn at bat. I was advised that legally it was possible to do that.

CG So the NEA did not initially consider museums?

GS The cost of running museums is two to three times the cost of running all other performing arts; dance, theatre, and symphony. Despite this factor supporting museums was never envisioned. We have gotten up to 15% of the annual Endowment budget and now are down to 11%. While we’re getting more money the Endowment’s budget has been going up so fast that we find ourselves with a smaller percentage; while the clear fact is that we should get a greater percentage because of the relationship between the fields of visual and performing arts and the cost of running them. I think that Pell and Brademas, House and Senate, felt that there would never be a proper shakeout there as far as money is concerned. I would agree with them. No amount of fighting that I have done in the past two years has done much for us in terms of a percentage increase. They put the IMS into legislation and there the thrust is different. It is money for straight, functional, housekeeping and maintenance, for salaries which are about two thirds of museums’ budget on average. Take a look at museum job listings to see how low salaries are. You are better off teaching public school than to earn eight to ten thousand dollars a year as director of a small museum. That’s not so true for the larger and better funded museums like the MFA.

When I was President of the MFA we instituted a policy where salaries were on a par with those at MIT and Harvard. There is a great difference in salary between working for a large or small institution. The result of that is that traffic has been to education, among art history majors, rather than to museums. Traditionally, it has been a profession for individuals with independent income. Today I don’t think that’s true. People come to museums because they have a calling. I would hate to be a young married man and director of a small museum trying to raise a family. Fifty years ago, curators tended to be dilletantes with a collector’s mind and inclinations.

(Rueppel did attempt to raise salaries for curators but at a cost. He mandated that they work full time for the museum and suspend outside income from consulting and teaching. They were to do any teaching at the museum. That happened to some extent. But they were not to hold university faculty positions. William Kelly Simpson chaired the Egyptian Department and was a professor at Yale. Ken Moffett had a half time position as curator of contemporary art and was tenured at Wellesley College. Later under Fontein, John Walsh was curator of European painting and a salaried curator of the William I. Koch Foundation. The arrangement doubled his compensation. Walsh left to head the Getty Museum just prior to my reporting his Koch salary, a conflict of interest, for the Patriot Ledger.)

CG When you were President of the MFA your reputation was that of a “brutal business type.” How did this jibe with the attitudes of clubbish Brahmin trustees and their emphasis on attaching their names to labels of glamorous acquisitions? You were regarded as an intruder because you reminded them of the bottom line.

How did you apply business practices to a museum?

GS A hundred and fifty years ago there were no museums. The few that existed did so to support egos and were the playthings of royalty. In their castles and estates, they had collections which the public had no access to. The French Revolution changed that as the public regarded the former royal collections to be in their domain. That transition from private to public occurred in a variety of ways. Tax revenue financed armies to loot treasures and being them home to national museums. In today’s world, tax deductions for museum donations mean that we all pay for those works. I think the public has latent knowledge of this. They say ‘I have an interest and stake in this. I don’t want to be shut out and want to enjoy it as well even though I lack an education in art history. It’s a part of our life and I have a right to it.’ My greatest difficulty at the MFA was espousing a viewpoint that the museum has a responsibility to the public.

It has to discharge that responsibility or some day the public will say ‘I don’t like the way that they run museums and let’s take them over and run them ourselves.’ On this point they have tremendous grassroots support. There is great belief in and a desire to be a part of them. There are awe inspiring things in museums. When I was a young fellow, you went into railroad stations and great public buildings. Today it’s different. There is not an impressive building that has been built in Boston recently. They have modest lobbies. Look at bus stations and airport terminals today. They are pretty utilitarian. Older museum buildings have the problem of not being inviting, seeming cold and repellant. That’s one place to start. They are lovely buildings and there are all kinds of places to show art in. In the last generation there has developed a problem of feeling at home in museums. People feel oppressed by their grandeur and scale. Then what happens when you are inside them? How does one get oriented? Who takes them through and says ‘now this label will mean…’ How do you install collections so that there is a sense of logical succession? Whether it’s all art or organized into departments. You demonstrate the point about how early Italian Renaissance art had no linear perspective. There is a narrative and sequence developed to convey that. Or how art develops to today’s abstract art where yet again there is no perspective. You convey how and why that happened and what it means to a viewer.

As trustees, I thought we had a responsibility as instruments of education to convey that in a manner which the public can grasp. To not just run museums for dilletantes and the occasional well-trained visitors. You have a dual purpose. That’s not been the most popularly held viewpoint.

The job of trustees is to represent the public to the staff and work out some understanding of what the public needs. Some very distinguished museum directors had a panel discussion here when Mr. Brademas was holding hearings. I heard them say that, by the year 2000, museums would be incorporated into the public education system of the United States and would no longer be independent institutions. Whether that becomes true or not I won’t be around to see.

CG Have you read the David Rockefeller chaired report (July, 1977) “Coming to Our Senses: The Significance of the Arts for American Education?”

(The report was prepared by the Arts, Education and Americans Panel of the American Council for the Arts in Education (ACAE). For many years the arts and education in the United States have been following separate tracks. This report was concerned with the implication of this situation for our culture, and it made recommendations for integrating the arts and education. A distinguished national panel conducted this intensive study, hearing testimony from numerous authorities, visiting schools and community programs, and conducting national surveys to develop new information. Data were gathered from every state on all levels of education, from kindergarten through high school. Community-based programs and higher education were also included in the study.

(In essence, the report concluded that art and education are indivisible, that the arts do not constitute a separate educational goal but rather pervade and energize all educational goals. Specific recommendations were directed toward making the arts an integrating force in American life. As an invitation to sustained national debate, the recommendations suggested recognizing the arts as a defining aspect of the last of the three inalienable rights. Through its recommendations, the panel helped bring to the pursuit of happiness the same weight of policy and institutional arrangements that have traditionally supported the rights of life and liberty. The report emerged as a citizen's guide for fuller realization of the third right.)

The report refers to that notion. It conveys that the arts and education must be allied. This is the approach that will provide relevance and generate funding for institutions.

GS I would have been at home with David Rockefeller on that. It could be problematic for a symphony orchestra but for the visual arts I would go right along with that. We are used to having visual art and visual opportunities around us all the time. We experience visuals far more than the performing arts. I am right at home with that idea. David asked me to be a part of the study, but because of the time it entailed, I couldn’t do it. David’s predecessor on that was Norris Houghton who ran the Phoenix Theatre and taught here at the Loeb Drama Center.

CG You came to the museum not through art but as a money person. Was it your role on the board to apply business acumen?

GS I don’t think so. It would have been a mistake because they weren’t ready for that and I’m not sure they ever will be. As I saw it, I was coming in with a fresh mind and fresh approach with no preconceived notions. My job was to find out what a museum was in today’s world and what it should be. I came to the MFA because I was interested in Brian O’Doherty’s TV broadcasts (WGBH from the museum).

(As O’Doherty told the Archives of American Art “I had a very wonderful sort of a graduate school, as it were, at the Museum of Fine Arts because I was the television lecturer, succeeding Barbara Novak, who became my wife. I had a curious nature, obviously, in every sense, and I had Cornelius Vermeule to instruct me in classical matters, classical art. There was Perry Rathbone, who was very good in contemporary art, in particularly on Beckmann, Max Beckmann. I had Dows Dunham, an Egyptian scholar. I had Kojiro Tomita in Asian art, who instructed me. I would go around, you see, and I'd ask them things. There was someone called Gertrude somebody and someone in fabrics and—that isn't quite the name of the department. Then I had another chap on drawings—Peter somebody. I've forgotten all their names now because it's 40, 50 years later. But they were all very—people of substance, worthy folk. Particularly Cornelius Vermeule was a very lively soul and his wife, Emily—both classicists.

“So there I was and all I had to do to find out something was to go and talk to them. And of course, I read Ananda Coomaraswamy; I read this; I read that, I read everybody. And I looked up each of the—you know the file that each painting has? And there's a wonderful collection up there. And so, for three years, I had a ball.”)

I wrote an article four or five years ago before Walter Annenberg’s ideas. I sent it to Tom Hoving at the Met and he said “My God, you’ve been reading our minds.” If you had a totalitarian society, and people were ordered into museums, even with that kind of regimentation, you could not get all the people in the United States to come to the MFA. You would only get a very small percentage. That being the case, is it not better to see the art of the MFA in reproduction than not to see it at all?

Since no country or museum has a monopoly on art, perhaps you put objects together in big exhibitions. But they have almost gone out of style because they are so expensive to produce. Despite the need and opportunities for them, there are now very few of these exhibitions in spite of support from the Endowments.

(Although not discussed in this interview Seybolt lobbied to have the federal government underwrite the insurance of museum loans for major international exhibitions. It was regarded as a major contribution to the field.)

CG Museums focus on the glamour of major acquisitions and exhibitions.

GS That’s not a fair thing to say about them. People impute the trustees more for that activity than anything else. What they buy is recommended by the staff provided there is money for its purchase. When there is money to acquire, say, British coins, it becomes a matter of what coins. It becomes difficult when three departments propose objects and there is only enough money to buy one.

In a well-run museum trustees don’t get into acquisitions. Given a choice they have a say but the director usually says this is what we prefer to buy.

CG Did your experience at the MFA serve as a prototype of what museums need?

GS It started there. I took on the trustees of the American Association of Museums three years ago. Since then I have visited museums all over the country. I am astonished to see how many I visited in the past five years. In this manner I learned of museum problems.

CG Can you be specific? Is it a matter of scale? Do the Met and MFA have the same problems, for example, as the ICA and De Cordova Museum?

GS The AAM defines a museum as an institution with a collection. The MFA’s basic charge is collection, preservation and education. I use the term exposition because it expresses a broader use of modern methods.

I don’t think collections are a mandate for public money. If you collect with public money that’s like most of the collections in Europe. America is too big for that. In Europe some 25% or more of the population live in large cities like London, Paris, Madrid, or Rome. That’s not true here as the nation is too large with diversity of scale in population centers. Under the law each state acts on its own. I certainly want to see that continue. We are not just discussing art museums. The IMS covers all kinds of museums including zoos and botanical gardens. How do you distinguish between elephants, paintings and plants? But you would have to were you to make acquisitions with public funds.

Tax laws in effect are public money and provide diversity as to how to apply them. Of the three precepts for museums the primary one, collections, is not for government funding.

(At the time of the interview contributions of works of art to museums were broadly tax deductible. In that sense the public paid for them. It was often abused as a loophole for the wealthy. But that’s how museums acquired masterpieces. Congress closed perceived loopholes and there is now less incentive for donations. Major collectors have opted to found their own museums. Artists donating works, for example, are limited to the cost of materials as deductions. Artists and dealers can arrange to “sell” a work to a collector with the understanding that it will be donated with a deduction for the purchase price. That’s how artists leverage their works into collections. But curators must be willing to negotiate deals through acquisition committees. Even gifted works come at a cost to museums which must store, exhibit and conserve them. Museums routinely deaccession works. Collectors are limited to the original purchase price of objects which must be documented. There are arrangements for partial donation and purchase in some cases.)

Secondly, there is a great need for preservation by all categories of museums. What we lack is an adequate number of trained technicians to do this work. They are very unevenly produced. Their skills are unevenly applied and they are too few. There are just not enough conservators to keep up with the demand. There are all kinds of problems with America’s treasures. Every day we are losing ground in this field. To adequately train and educate a critical mass of technicians entails a generation. There has been a beginning of this and regional conservation centers have been developed.

(An example of this is the Stone Hill Center on the campus of the Clark Art Institute on Williamstown.)

If you have the lab and equipment facilities you can recruit and train personnel. By and large, however, museums have not budgeted to hire these individuals who have completed their training. Museums, particularly smaller ones, at best outsource conservation which is expensive. Perhaps money might be provided to museums as challenge grants. All museums, no matter what they collect, have common needs. Paper is paper, wood is wood, and metal is metal. If individuals are trained to handle certain materials those skills may be broadly applied.

We are so far behind that it will take a generation to catch up. This is a great need not being address by museum budgets. There is no guarantee that people with this special training will remain in a field that is not supported. We’re losing ground every day. It goes at least at an arithmetical rate. There are no known studies that project the scale of the problem, for how many years, and how many millions. This should be done. Museums will tell you that they have a problem but rarely in terms of how many man or woman days it would take to deal with it. The conservators that they have are just working day-to-day to stay ahead of it. They don’t have time to stop and spend three months surveying the problem. That has to be done with outside funding.

Exposition and education are a third important area. In the traditional forms of media: print, catalogues, magazines most museum professionals are more eye than ear minded. When they discuss education, they think of something on paper. They don’t consider other forms of media but they are now beginning to more than they used to. The world has changed in regard to how it receives education. There are all forms of new supplements and inputs one can receive.

CG It is notable that the Annenberg Communication Center proposal for the Metropolitans Museum has gotten bad press and not just for potentially encroaching on public land in Central Park. Setting aside real estate issues it seems to be unpopular in art circles.

GS Five years ago I wouldn’t have written an article about all this if I didn’t believe in it. Seeing the nation’s art on TV is better than not seeing it at all. Most art needs a visual quality to it but it is better to do that than nothing. Regarding teaching aids, we do an abysmally bad job of art education in our schools. When I was a boy you got shop or music. You got a hammer and saw or an hour squirming in an auditorium listening to records.

Today the world is more sophisticated particularly in America. Most schools do something with art education but it doesn’t prepare students to deal with museums.

CG Are you aware of Cultural Educational Collaborative and what they are doing to integrate schools through cooperation between public schools, museums and performance groups.

GS I agree with that, particularly larger museums with enormous collections. They don’t really make them available to students. A pioneering program entails objects from the MFA loaned to smaller regional museums like Brockton and Fitchburg. That allows school groups to see Greek and Egyptian works that would otherwise be in storage. I am not suggesting long term loans of the best objects.

(That did occur later when the MFA formed a relationship with a museum in Nagoya, Japan. During the administration of Malcolm Rogers, loans primarily of Impressionist and Post Impressionist masterpieces, were regarded as a funding resource. This went beyond the norm of museums exchanging works for major scholarly exhibitions.)

Museums have objects in storage that they don’t use. But they are good enough for long term educational loans to small museums. They are not the finest or greatest pieces. A problem with major exhibitions today is the cost of publishing catalogues. Printing three to five thousand copies in color is a money losing proposition. Sales and getting it into circulation do not match the cost of printing. Installing and designing exhibitions has become a field for professionals. That and curatorial resources entail a lot of money. If, however, one developed efficient traveling exhibitions, printing say 50,000 copies of a catalogue, it could be cost effective and sell for less money. You could then better absorb research, writing and production of a catalogue as well as other costs. You could tour that exhibition with installation diagrams and swatches for wall colors.

That kind of show could tour for a couple of years and be seen in twenty or so venues. The host museum would pay a share of admission to the lending institution.

(This is precisely what happened particularly when museums closed for a year or more for major renovations. That also creates the qui-pro-quo that, once reopened, the lending museum can borrow objects. Concerns were raised about risk of traveling objects over a span of more than a year to multiple venues. These extended loan show, however, have become the norm for major museums. The era of “blockbuster” shows developed in the 1960s and proved to be competitive. A major Renoir show for the MFA, for example, drew an audience of 500,000 and balanced the budget for that year. Those shows have become ever more expensive to produce particularly for handling and insurance. The public, however, has come to expect them.)

By helping other museums through loan shows the lending museum helps itself. The shows now being organized for the Brockton Museum, for example, should be circulated to ten museums.

Four years ago, I put together a proposal to approach major foundations like Ford, Rockefeller and The National Endowments. I wanted them to put up $100 million to establish a fund that would earn some five to six million a year. It would be best to gear this to museums as the cost for funding the performing arts is far greater than the per diem costs of supporting a company for example. When moving a museum’s objects, you don’t have that problem as there is no maintenance (of personnel). I tried to create a pool of money which could be drawn upon to start this thing.

Major museums have a lot in their basements where smaller museums have little or nothing in reserve. Drawing on storage resources would be a boon to the entire field of museums in America. That’s an example of what could be done for education and exhibitions on the part of the federal government.

In time, if a museum does not put together a good package, and its loan collections are not well received, the smaller institutions are not going to take those shows. Museums that do this well, through the volume of use and revenue that generates, will do a better job.

The smaller museums will judge whether an exhibition is too expensive or esoteric. They might opt for another museum’s program if it has wider appeal for their audience and market. The offering may appeal to an audience in Kansas or Iowa. It is an opportunity of its constituency to see objects from Boston. Some 50,000 people in Kansas City, for instance, will have an opportunity to see that show. They are having an experience that they wouldn’t have other than on TV. It is also possible to have the TV programming in that city at the same time as the exhibition. You can also have sound and video presentations for the schools and it is all packaged for that city at the same time.

When the Kenneth Clark series Civilization was produced for TV I wanted to buy a set of prints and set up a foundation for schools to be able to borrow or rent them. We would put up several thousand dollars and buy the prints. The shipping and receiving would happen here (his corporate headquarters). To my surprise a number of schools purchased their own set of prints. If the MFA and other institutions created libraries of educational films then schools could include them in their curriculum. Harvard does this for their film classes. They rent films that they show.

CG Why don’t people want to accept the Annenberg concept at the Met?

GS I don’t have an answer for that. I just don’t understand it. I think they are going to increase their audiences by eight, ten and fifty. In the article I wrote I mentioned that this should naturally fall into major centers of communication.

(A 1976 pledge of $20 million to the Metropolitan Museum for a communications center to make the world's art more available to mass audiences was made by Walter H. Annenberg, former Ambassador to Britain and a Metropolitan trustee since 1974. It was set up as a division of the Annenberg School of Communications, which also has branches at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Southern California, the center marks the first joining of a school of communicational with a museum. The center uses “the most advanced techniques of modern communications”—films, television, tapes, publications, slides, reproductions and other devices—to disseminate information about art for the widest audience, ranging from the general public through graduate students in fine arts.)

I was visiting WGBH the other night and they told me that they generate some 35% of educational programming in the United States that is shown nationally. It is natural to do this in urban setting like New York, Boston or Chicago because of the critical mass or resources.

CG Would Boston be a likely location for this programming?

GS There are unbelievable opportunities here to resource the product of museums, aquariums and botanical gardens. The kids in Hannibal, Missouri, where I come from, know about catfish. They have heard about sharks and whales but have no idea what they really are. It’s an index of things that are interesting to them. You put in $100 million to get started but what are the returns for the American people in general?

CG The combined National Foundations for the Arts and Humanities this year has a budget of $250 million. It has taken time to get to that level.

(For 2020 the NEA has been funded at $162 million and the NEH for $162.25 million.)

What will the IMS need to be effective?

GS The museums need at least $150 million. The $3 million for next year is more than the endowments started with years ago. At this point we would waste money if we were appropriated $40 million. In the long run though we will need $150 million. This isn’t to start new museums. There’s a building and it needs to be lit and heated. There are guards and staff expenses. Doubling attendance doesn’t cost that much. If you get 200,000 people to come to the museum for a successful exhibition then everything comes to life. The restaurant and sales desk all do business. For an MFA that can make or break the institution. If you can draw a million visitors a year that solves all fiscal challenges. Currently annual attendance is half that. When a museum has financial struggles, it becomes intellectually and emotionally bankrupt. What gets pealed off the top are people that represent the real talent of the museum.