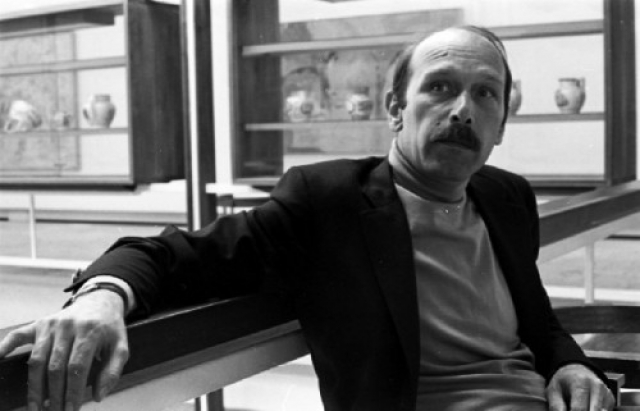

Carl Belz at 78

For 24 Years Director of Rose Art Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 03, 2016

A graduate of Princeton, where he was a star basketball player, Carl Belz earned a Ph.D. there in art history. In the 1960s he joined the faculty of Brandeis University and in 1974 took over as director of the then moribund Rose Art Museum.

He remained director of the Rose for the next 24 years but was forced out when Lois and Henry Foster, the primary donors of the contemporary art museum, planned an expansion designed by Graham Gund.

Belz died recently of a heart attack at 78.

He took over at the Rose during a bad period for Brandeis. Many of its graduates had taken to heart its liberal and radical education. Several made the FBI most wanted list.

Conservative Jewish philanthropists shifted their attention to supporting Israel.

Brandeis which was founded and flourished after WWII under president Abe Sachar had expanded rapidly with a dense campus that was heavily leveraged.

When Belz took over at the Rose it was a shadow of its former self. It was founded by the flamboyant curator, historian and entrepreneur Sam Hunter. He created a core collection of works by Pop art masters which set the museum along the path of housing one of the finest contemporary collections in the Boston area if not New England.

Following Hunter, who passed away while a professor at Princeton, he was followed by another distinguished Princeton professor and former MoMA curator, William Seitz.

Belz took over as the fourth Rose director with a skeletal budget for programming. With severely limited funding he focused on showing and promoting local and regional artists with particular support of women. This emphasis was augmented with the later hire of Susan Stoops as curator. She is now a curator with the Worcester Art Museum.

As Brandeis gradually recovered so did support for the Rose. There was an annual Lois Foster exhibition mounted during commencement. This entailed shows and catalogues with major artists.

After being forced into retirement from the Rose, for a period of time, he was editor of Art New England. The co-publisher of the magazine was his daughter Portia. She later sold her interest in the publication.

Over the years of his tenure I often met with Belz to review exhibitions and discuss contemporary art.

What follows is the first of three installments of an interview from 2011. There are links to the second and third parts of the dialogue.

Charles Giuliano I was an undergraduate when Sam Hunter launched the Rose Art Museum. There was money then. I attended and was amazed by the legendary Larry Rivers opening when the champagne flowed without stop. He played jazz, alto sax, with a combo. I knew more about jazz, and I thought his playing was mediocre. I was just learning about art but had similar doubts about that aspect of Rivers.

From that era, I also recall a James Brooks exhibition, a relatively marginal member of the NY School. Also, there was an important show of the late paintings of Franz Kline, and I believe one by Milton Resnick. Hunter brought Robert Motherwell to speak. I recall him discussing “Pancho Villa Dead or Alive.”

It was very different from what we were being taught in the studio by Mitch Siporin and Arthur Polonsky. Of course, Peter Grippe was trying oh so hard to be avant-garde. Which mostly meant going out drinking with him. I spent one evening class throwing up as we had gone drinking between afternoon and evening studios.

In the Justice, I fought with Hunter when he used the Poses Foundation money to host a mega-colloquium of the A list of the New York School. It was an astonishing event, but the problem was it was held in June. Since I lived in Brookline, I was perhaps the only student to attend the event. Sam seemed more focused on wining and dining his pals than serving an educational function.

Of course the Brandeis I am describing (Class of 1963) is very different from the Rose that you took over after the second director, Bill Seitz.

Your tenure started post Sacks and Powers when Brandeis Grads made the Ten Most Wanted FBI lists. My chemistry lab partner (I flunked) blew up a bank as a Weatherperson.

When you started at the Rose the cupboard was bare. Can you describe the resources and ground rules when you took over?

Carl Belz Let's first back up a few steps. I didn't take over from Bill Seitz, I took over from Michael Wentworth, who was Bill's assistant director and became director when Bill left Brandeis in 1971. Wentworth had been hired in 1970 to replace Russell Connor, who did "Vision and Television" and shortly thereafter departed for the Whitney Museum of American Art. When Russ left, Bill actually asked me if I'd be interested in the assistant director position (Bill had been my teacher at Princeton and had, along with Joachim Gaehde, interviewed me when I was hired by Brandeis in 1968), but I declined. I was just in my second year at Brandeis, I was getting to know the Boston area gallery and artist situation, I was writing criticism for Artforum, my "Story of Rock" had just come out, things were going well and I figured I'd go with the flow of the situation; besides, it looked to me as though Bill mostly wanted someone to run the museum's day-to-day business while he did the bulk of the exhibition planning. So Wentworth became acting director, his contract ran until 1974, and I became director on July 1 of that year.

Resources: The resources were scant, but having limited museum experience, I didn't initially have any idea about just how scant they were. Apart from salaries and operating supplies, there was, as I recall, an exhibitions line of $4,000, which was supposed to support an exhibitions program of five or six exhibitions for the academic year--you do the math and, like me at the time, you'll pretty quickly see what scant meant. Years later I found an old budget sheet in the files for 1968-69 that included $20,000 for exhibitions, which seemed the high water mark for university support, one that stood for years. Given the budget constraints, I quickly saw the value of having a great permanent collection from which countless exhibitions could be generated whenever you ran out of dough to curate temporary shows from the art world at large.

Ground Rules: Upon assuming the directorship on July 1, I learned that an alumni exhibition was in the works, a project that was being launched in partnership with the Brandeis University National Women's Committee. Ground Rules #1: The BNWC never paid for anything, never ever, they only raised money--for the library--end of discussion; thus, Ground Rules #2: Since no one briefed me about anything having to do with the museum's operation, not Michael Wentworth, not Dean Gaehde, no one, so Rule #2 was clear: You fly by the seat of your pants and find a way to make it happen. So I followed up on the initial letters that had been sent to alumni artists, I decided from the outset that there'd be no jurying of inclusions, it would be come-one-come-all, no politics, no rejections, and no hard feelings, it would be a feel-good event for the museum and the university. Which from my point of view it was--surely you remember, you were represented with four or five watercolors, Andy Tavarelli was in it as a special student, Joel Janowitz, Paul Brown, Jo Sandman, Sid Hurwitz, and Peter Lipsitt too, some pretty good people. But that brings me to Ground Rule #3: Talk to the founder of the Department of Fine Arts, Mitchell Siporin, before you do anything! Alas, I learned that rule only after the fact, after the opening of "A Generation of Brandeis Artists," when Mitch sat me down at lunch one day and told me about everything I'd done wrong, how I'd missed the opportunity to celebrate the art department, and on and on and on it went, and I have to confess it kind of soured me for a while, my first clue about how and why college and university art museums always have some kind of tension in their relationship--and not just at Brandeis but in lots of places--a tension having to do with control and/or autonomy, like: does the museum exist first of all as a resource, a "laboratory," for the art department--with faculty and student shows, "teaching exhibitions", etc.? or is the museum a separate and autonomous unit within the university, focused on a program generated and conducted by its professional staff, one that may from time to time intersect with the art department but is not mandated by its mission to do so? The latter option, henceforth and effectively, became Ground Rule #4, and it replaced Ground Rule #3.

Additional ground rules gradually evolved as part of my on-the-job training, but the ones I've listed should provide the start of an answer to your question.

CG Your mention of Joachim Gaehde and Mitch Siporin jogs my memory of the Brandeis fine arts department as well as issues surrounding the alumni show that you organized and which I was pleased to be included in.

Gaehde later became a dean but I recall him as an art history professor. I took a seminar with him on medieval manuscripts. Rather than slides he brought to class wonderful art books with facsimile reproductions. One was totally seduced by his charm and handsome eloquence. I recall being so impressed by his elegant shirts with cuff links. His wife was a distinguished works on paper conservator.

More important to me was the influence of Creighton Gilbert whom I still regard as my greatest mentor and the most brilliant man I have ever known. His seminars on Michelangelo and Caravaggio were indelible. Far more insightful than any I attended in graduate school. He took a great interest in me and we stayed connected for years after. I regret that I did not hold onto his warm and wonderful letters, often gently scolding on matters of spelling, grammar and syntax. Something you struggled with when briefly editing me at Art New England.

Of course the star of the department was the showman, mystic and shaman Leo Bronstein. I took his classes on medieval and Islamic art. Also I showed slides for his classes (pre power point) and as I had a car I used to drive him home to Cambridge. So I enjoyed his intimate company on those occasions.

Looking back the art historians were on a higher level than the studio faculty. Your report on that lunch with Siporin is an all too vivid reminder of his limitations.

Which raises the issue you touch on about the relationship between university art museums and the fine arts departments. Under founding Rose director, Sam Hunter, there was no relationship. The museum was completely independent. Just imagine if I had the chance to take a class with Hunter and to work with the objects of the collection that he acquired for the museum. So, unlike the Fogg at Harvard, the Rose was not created as a teaching resource. It was more of a treasure house and memorial to the founders.

During a four month period in 1962 and into 1963 as Hunter describes it, “Leon Mnuchin called from New York one day to announce that he and his wife, Harriet Gevirtz-Mnuchin had inherited a sum of $50,000, with which they wished to fund a contemporary art collection at Brandeis.”

Hunter reports that he and “Leon immediately set out to explore the galleries. We often made gallery rounds with Robert Scull, a friend of Leon’s and a prominent New York collector,” especially of Pop Art. They acquired early and important works by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselman, James Rosenquist, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, among many others. Their limit was $5,000 a painting (which meant several were bought for much less). Warhol had already become a bit expensive, Hunter says, so they went for one of his lesser works from the “paint-by-number series.” Hunter’s successor at the Rose, William Seitz, exchanged the Warhol ("Do It Yourself Sailboat," 1962) , for "Saturday Disaster," 1964. The Gevirtz-Mnuchin collection is worth in excess of $200,000,000.

Consider the limitations of the architecture of the original Harrison and Abramovitz structure. There is that absurd staircase than limits the ability to back away from the work on two levels. With a ridiculous reflecting pool dominating the lower level. Around the stairwell on the upper level, originally, there were vitrines displaying examples of the porcelain collection of the donors. They were a non sequitor with Hunter’s vision and mandate to focus on contemporary art. As well as obstructing site lines.

I am sure you struggled with the limitations of the space. The lower level addition and storage/ office relieved the pressure. But I regard the Foster Gallery addition designed by Graham Gund as numbingly mediocre. There is no continuity or sense of movement through the space.

By contrast I have been talking with Lisa Corrin who is leaving the Williams College Museum of Art. Its collection is used not only for hands on teaching of art history but is accessible to all departments of the college. There is a staff curator who works with faculty to pull together objects for classes.

So looking back at Brandeis there wasn’t that kind of intimate connection between the Rose and the fine arts department. I’m sure it was different under your watch. But as is unfortunately the norm you did not appear to have a joint appointment as faculty member and museum director. You taught classes as an adjunct to the department. There seems to be generic resistance to connecting the dots in academia. Departments guard their turf.

During his time at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, Peter Bowron attempted to endow curatorial positions and create a clear demarcation from the fine arts department. He met with resistance in attempts to open up the Fogg and make it more accessible.

So I would like to hear more of your thoughts on the issue of an art museum and its relationship to an academic context. When I spoke recently with John Stomberg, who is taking over as director of the Mount Holyoke Museum of Art, he told me that he will also hold a joint faculty position. During his time at Williams he was an adjunct to the art history department.

CB Today's agenda: (1) The building and (2) The question of the Teaching Museum.

(1) Designed by Harrison and Abromowitz, Brandeis house architects during the university's rapid growth in the 1950s and 60s, the Rose Art Museum was for all intents and purposes functionally inadequate from the day its doors opened in 1961. To me, it was as though Abe Sachar had decided a facility was needed to house an art collection that had been accumulating since the university's beginning, he had a donor in hand, and he asked Max Abromowitz to design a museum, with little or no thought--none that I ever came across, in any case-- about its program and/or mission, let alone its day-to-day practical needs. Thus: storage space consisted of one closet-like room about 10 feet square with a ceiling about seven feet high, meaning the collection continued to be stored off site, mostly in Spingold Theater and Golding basement; office space that barely accommodated the assistant director and his secretary along with the museum registrar, meaning the director and his secretary had offices in Spingold; and there was no space for shipping and receiving or exhibition preparation, meaning the two preparators were also housed in Golding.

So the museum essentially consisted of two large galleries, one upstairs and one down, and that was about it. Except there was an elegant central staircase connecting the galleries that had a landing where visitors could pause to look at the reflecting pool that occupied the entire center of the lower space. I've always thought the staircase was Max's version of the classic staircase associated with so many of the great American museums built early in the 20th century--the Met, Boston, Philadelphia, etc.--whether indoors or out or both, the staircases were a symbol of ascending to the level of the muses where you could contemplate the arts, and the Rose architecture did the same thing, you went down instead of up, but you still ended with the contemplative environment, which was what the pool meant. And then, as you point out, there were the display cases intended to house Mrs. Rose's ceramic collection, positioned on either side of the upper gallery and thereby turning the space into a pair of corridors that were best suited for pictures, not sculpture--certainly not large scale sculpture (I used to wonder if Max would have done it differently if he'd designed it five or six years later, after the revival of monumental sculpture that came with minimalism).

I became director shortly after a new wing was added in 1974--to provide office space, collection storage, and preparator space, all the stuff that had not been accounted for in the original building. Plus two galleries, one of which, with built-in corner display cabinets, was initially intended to be a period room for Mrs. Rose's ceramics, but that idea was nixed when the budget wouldn't accommodate the elevator she requested be installed to enable her to visit her collection. Which left us with a weird space that was always a challenge to fill.

I've never set foot in the new Foster wing, but I know enough about it to recall the old saying about how "the more things change, the more they remain the same." I gather--strictly second hand, but reliable--that Hank Foster picked Graham as his architect and that Graham went ahead pretty much as Max had, doing his thing without much regard for the museum's needs at that particular time. I'd have thought, for instance, that additional storage space was needed by that time, along with enhanced facilities for studying collection objects and/or hosting meetings or classes, all of which we clearly needed by the time I left in 1998. Which brings us to...

(2) The Teaching Museum aka relations with the art department. As indicated above, there seemed never to have been a discussion about what kind of museum the Rose would be. What happened, it seems to me, is that the museum became what its first director was, and it continued with what its subsequent directors were. Sam Hunter was a modernist, so the Rose became modern and contemporary. Bill Seitz, a PhD from Princeton and initially a painter, came from MoMA also as a modern and contemporary, but his art historical background made him sensitive to art's larger history, so there were some "old masters" around, giving the impression that maybe someone thought the Rose would eventually be an encyclopedic museum like so many of the older college/university museums--which never happened, and was never going to happen, and it was in my tenure that we drew that line and sold the "old masters"--all but one of them school pieces or followers, with the exception of the Strozzi, which pissed off Elaine Loeffler--which we did (1) to define our mission as modern and contemporary and (2) to some get endowment. As far as mission was concerned, I figured we could afford to specialize, because it meant doing what we did best--we're weren't ever going to compete or enlarge significantly upon the old masters at the MFA or the Fogg or the Gardner, so let them carry that ball and we'd carry the contemporary ball.

Which IMO meant we who were connected with the Rose were thinking about our audience, including our students, even though there wasn't any formal relationship with the department. I was an adjunct as you know , I taught a history of contemporary art, but I soon started a seminar on museum methods and procedures. And some pretty good students found their way to the Rose--Gary Tinterow and Adam Weinberg, among them--and in that sense I'd say we were very much a teaching museum, though not in the conventional sense. In addition, I occasionally did an exhibition of art department faculty, a retrospective of Mitchell Siporin in 1976, for instance, a couple of new studio faculty when they came on board later, the Jonathan Borofsky GOD Project in the late 90s, along with independent studies interns on exhibitions I was working on and so forth, all of which meant our doors were always open to the members of the art department, and I periodically invited the historians to propose exhibitions if they wished, which actually happened a couple of times over the years, so that was our relation to the department The way I see it is that we were foremost a museum that contributed to the discourse on the art of our time, we were active and ongoing "players" in that field, players to a far greater extent than anyone in the art department--and that's what we had been from the beginning in 1961 and continued to be after I left (though, if you don't mind my saying, no one's ever taught as much as I did) Now, however, it appears there's a move afoot to make the Rose a teaching museum in the more traditional, conventional sense where the university audience--students and faculty--are the primary focus of the staff a la Wellesley, Smith, Harvard, Yale, etc. where the staff is pretty much service oriented and the museum's intellectual contribution, which varies widely from institution to institution, comes via faculty in the art department who from time to time put together an exhibition based on their research. Which is fine, I guess, I mean how do you fault those institutions, right? If that's the case, however, it's got to be recognized that the Rose won't any longer be the museum it's been for the past 50 years, it'll be an administrative unit of the university, a service department. Which is maybe just the way it goes...it's certainly better than having its doors forever closed.

That should do it for now, phew!