Picasso Looks at Degas

Clark Art Institute to September 12

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 24, 2010

Picasso Looks at Degas

Curated by Elizabeth Cowling and Richard Kendall

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

Williamstown, Mass.

June 13 to September 12, 2010

Museu Picasso

Barcelona, Spain

October 14 to January 16, 2011

Catalogue: Essays by the curators as well as by Cecile Godefroy, Sarah Lees, Montse Torras. Yale University Press, 2010, 354 pages

Yet again in the special exhibition galleries of the Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Mass. big things come in small packages. The museum is under renovation with an expansion of its jewel box galleries. For Picasso Looks at Degas the exhibition is expanded with additional galleries off the main entrance. By the Clark’s standards this is a large show but compared to spaces at major museums this is a compact project.

Interspersed in the exhibition are some paintings but the primary focus is on intimate works on paper. The undertaking seems vaster when perusing the catalogue than an actual tour of the show.

The depth and impact of what is displayed is so dense and complex, however, that it has taken most of the summer to write this essay. The process started with seeing the show some time back. Then trying to find the time to read the text. The curators took several years to organize this project.

Yesterday, a Saturday, we returned for another look. Having read the essays it was engaging to see the image informed by curatorial research and insight. Actually, it was challenging to get close enough to look at the works. The issue was the success of the show which meant densely packed galleries particularly in the smaller spaces. Even parking was tough.

Of course it is nice when museums have these problems. There is that long off season when one may be quite alone with the work. Even vast Mass MoCA has been mobbed when we have visited on recent weekends.

It is great to visit crowded museums unless you really care about art. Of course mostly this reflects tourism and fashion. It has become the thing to do. In a sense I miss the days, not so very long ago, when museums were deserted. Now trying to see great works is like a contact sport. You have to aggressively elbow your way up to the work and rudely shove aside or duck in front. There are obstacles with head sets spewing out Cliff Notes, in properly curatorial art speak, about this or that masterpiece. They stand planted like trees in front of the work.

It can be discouraging. The trick perhaps is to find an off peak time to drop by.

Years ago when the Treasures of King Tutankhamun was on view at the Met I visited during the Super Bowl. On that Sunday in New York I had the Pharaoh all to myself. It was actually my third visit having seen the show twice in D.C. After the tour of Tut I was able to catch the second half of the football game at a bar.

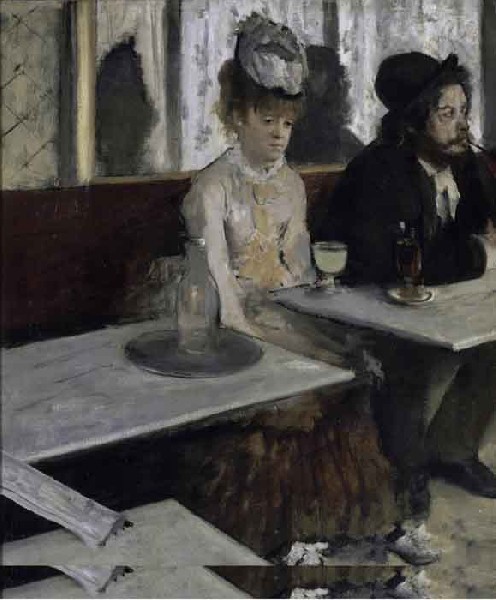

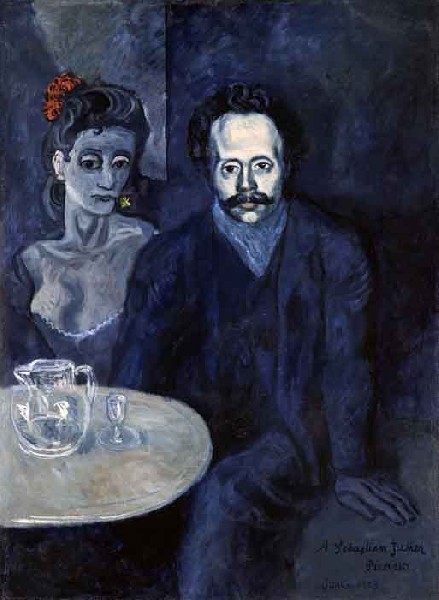

The two visits to the Clark combined viewing old friends and very familiar works as well as fresh discoveries. One of the greatest of the works by Degas “In a Café (L’Absinthe)” 1875-76 was borrowed from the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. It was hung next to a Blue Period painting by Picasso “Portrait of Sebastia Junyer i Vidal” 1903 from the LA County Museum of Art. From the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. was “The Blue Room” 1901.

Because this exhibition was a joint project with the Museu Picasso in Barcelona we enjoyed seeing so many of the early drawings and paintings in that museum. The core of the collection was donated by Picasso’s on and off secretary, the Catalan poet, Jaume Sabartes. Instead of cash Picasso often paid him with drawings. He left many of these works to the city which created a museum in honor of its most famous citizen.

At the Clark it was wonderful to see its small Degas “Self Portrait” juxtaposed with a similarly scaled one by Picasso who was then only about fifteen. Seeing them together was just thrilling.

The vast majority of visitors to the exhibition just pass through with a glance here and there. They take in the experience in the broadest sense. Perhaps they linger over what is already familiar such as the Clark’s example of the editioned bronze “Little Dancer-Aged Fourteen.” It is a sculpture familiar from a number of collections. The dance pastels may arrest their attention.

While there is the enticement of comparing and contrasting the works of Picasso (1881-1973) and Degas (1834-1917) in the broadest sense this is a concise project with a fixed scholarly mandate. Often blockbuster exhibitions of familiar artists have no motive beyond luring vast audiences. In this case, however, what may not be evident to most viewers, is that the curators have assembled a lot of hard evidence in defense of a very specific point. That, during all phases of his career, Picasso looked long and hard at the work of Degas.

In a wall text of the first gallery of the exhibition is the famous Picasso quote that "Minor artist borrow while great artists steal."

Although their lives and careers overlapped, Picasso was an established artist of 35 when Degas died at the age of 83, there is no evidence that they ever met. They did not travel in the same circles and Degas was sick and virtually blind in his last years. Picasso knew the work of Degas through dealers he had traded with.

The argument that Degas influenced Picasso is most tenuous in the beginning of his career but became stronger and more didactic as it progressed.

In the first floor gallery a selection of drawings strives to conflate the academic studies of the teenaged Picasso with the classical drawings of Degas, which in turn derived from Ingres, and before that David. The curators suggest a linkage between generations of masters in the precise rendering of the figure. What weakens the argument is that these early works by Picasso predate Paris and French influences. His first lessons came from his father, a minor academic. Some of the earliest paintings and drawings were at first, family members, and then his generation of art students and poets.

The first trip to Paris at the age of 19, in 1900, was a disaster. He had hoped to travel on to London. In fact he never did and rarely traveled other than between France and Spain. During World War I he escaped Paris for Rome. As a Spaniard he did not enlist in the French army as did his partner Georges Braque. During WWII German officers visited his studio. To be sitting in Parisian cafes out of uniform was considered unpatriotic.

Things went so badly during his first trip to Paris that he crashed with Catalan friends, managed to make some work, and had to borrow money from his father in order to return home in December. During that brief visit he sold three sketches to the art dealer Berthe Weill. In 1902 she exhibited 30 of his Blue Period works. That exhibition estalished him in the Parisian art world.

When Picasso returned to Barcelona he brought Post Impressionism back with him. This is evident in the intriguing painting “The Dwarf” 1901 which is one of the major loans to the Clark from Barcelona. The painting conflates the broken brush stroke he learned in Paris with a subject from Barcelona. The Dwarf in question was a well known prostitute and madam.

While most viewers of this exhibition will dwell on the dancers, there are indeed nice connections between the masters, it is the theme of the brothel which is most unique and original about this stunning exhibition. Before we move on to that, yes, both Picasso and Degas loved the ballet. It was an obsessive subject with Degas. The Clark is showing works from its collection. And Picasso became enamored of the theatre even marrying a dancer from the Ballet Russe, Olga Kaklova. He met her in Rome while collaborating on the dance “Parade.” There is a gallery devoted to this connection.

Today the notion of actually paying for sex seems curious. It is so readily available. Now and then a philandering politician gets caught with his fingers in the cookie jar. The media makes a big fuss. Today, teens and college kids “hook up” like rabbits. No big deal.

During the time of Degas and Picasso sex was not that readily accessible. In Spain a young man had to marry in order to fornicate. Engagements typically lasted for years. All courting was chaperoned and there was no dating. Young men went to prostitutes. Picasso and his pals prowled the cat houses of the Barrio Gotico.

The significance of “The Blue Room” 1901 when he returned to Paris is that it may depict Picasso’s first live in girlfriend. She is bathing in a tin tub of a rented flat. There are paintings on the walls and a Lautrec poster of the dancer May Milton. The face of the blonde woman is generic and she has no pubic hair. The artist may have protected her identity and modesty.

There have been attempts and theories to identify her. Most likely she lasted only briefly with the young starving artist. Picasso learned that French women were willing to have sex without marriage. He would marry only twice, to Olga, and late in life, Jacqueline, with dozens of mistresses in between. Often the wives and girlfriends of friends and even collectors. As a macho Spaniard, however, he was abusive and possessive. The biography by his long term mistress and mother of two children, Francois Gilot’s “My Life with Picasso,” is harsh and unforgiving.

The sexual persuasion of Degas is a mystery and the subject of considerable research and conjecture. He remained a bachelor and is often described as a misogynist if not a misanthrope. Another opinion is that he adored and doted on women. There was a curious relationship to the American artist Mary Cassatt. Initially he encouraged and championed her. He painted her many times. But when she became well know there was a falling out.

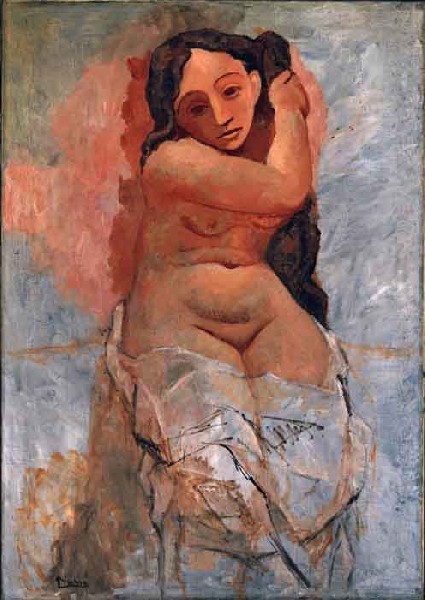

Scholars discuss the compassion for women expressed in his many studies of bathers and laundresses. These views are devoid of the male gaze typical of the salon nudes. This show has examples of those works as well as similar themes by Picasso. But the connectivity seems tenuous at best. There is a Degas painting of fatigued women yawning while ironing. This is juxtaposed by Picasso's expressionist “Woman Ironing” 1904 from the Guggenheim Museum. They are so different in mood and feeling that they make for an apples and oranges comparison. It’s a wild stretch to evoke Degas in this painting which just happens to depict a woman ironing. It is something Picasso may have seen at home rather than being inspired by a visit to a gallery or museum.

The series of studies and monotypes that Degas created in brothels is generally thought to be an obscure and little understood aspect of the oeuvre which came to light in the posthumous sale of his estate. It is when sculptures in various states of neglect were discovered. These ephemeral works in clay and wax were cast as the many bronzes we know today.

The essays in this meticulously researched catalogue reveal that the erotic work of Degas was well known to collectors through several dealers. Picasso would have known of these works at a fairly early point in his career. Perhaps as early as 1907 when he created his great work on a brothel theme “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” It is the masterpiece that immediately led to Cubism. There is an important study for the painting in the Clark exhibition.

Several years ago I had in depth conversations with Wayne Anderson when he was writing a book on that painting. While William Rubin gave an iconographic, erotic, psychological interpretation to the slice of melon in the painting, as perhaps a splayed vagina, Anderson thought it was just a piece of fruit. Wayne discussed how the brothel was kind of a club or hangout for men. There was food, drink, music, the company of the madam. It was about more than just sex.

In Picasso’s painting it is a ferocious, charged, jungle like environment. The faces of the women have become grotesque masks. It conveys anger and hostility to women. It evokes the primitive misogynistic impulses that would surface in the strident, horrific, powerful and emblematic “Women” of deKooning.

The women in the brothel images of Lautrec, Degas, Picasso and Brassai’s photographs, seem so grotesque that one wonders why men paid money to have sex with them. It is interesting to compare these realistic depictions of actual prostitutes with the fantasies invented by Hugh Heffner in Playboy. In the Playboy fantasy she is the gorgeous girl next door with a fabulous body, pretty face, and easy virtue.

The women in the Degas monotypes are whores. No illusions. There is a great emphasis on their smudgy, black snatch. The sexuality is so blatant that it isn’t even erotic. There is no room for fantasy.

How different from the paintings of Edouard Manet. His Victorine Meurant paintings such as the famous “Olympia,” 1863, depict a woman/ mistress who was also a sex partner, collaborator/ model and companion to the artist. There is a lovely portrait of her in the Museum of Fine Arts which has nothing to do with sex and is more about love. Manet depicted the beautiful, charming, erotic women who were mistresses and companions of rich men. They were courtesans not hookers. These are the women that Emile Zola wrote about in “Nana.”

Degas seemed fixated on the lowest end of the sexual spectrum. Did he indulge or just observe? Hard to say. The monotypes are too clinical and realistic to imply any fantasy. Degas never depicted a penis but Picasso did. But there are none of his hard core drawings in this show. The Clark has organized a R rated show. Pity.

But there was a curious sense of voyeurism in the “erotic” gallery. The selection of Degas monotypes were displayed in low cases underneath the suite of late prints that they inspired from Picasso. By then Picasso was an old man. One might add a dirty old man. The series of prints is all about naked lust. How different they are from the sublime eroticism of the Suite Vollard of 1939.

In the crowded gallery I had to push in through a throng of people and bend down to study the small monotypes. There was a sense of compromise in taking this humiliating posture. The more so when I put on glasses and attempted to study the images many of which were reproductions. Viewing them in the catalogue in the comfort and privacy of home was a quite different experience. At the Clark I wanted to study intimate details of these priceless and rare originals. This may indeed be a once in a lifetime opportunity.

When Picasso was rich and famous he was able to collect. Artists often build their personal collections through trades. This may entail swapping with other artists or through trades with dealers. Picasso was notorious for not paying for anything and hording. He was known to fill studios, lock them up, and move to new ones. So the Degas monotypes he acquired may have been just an aspect of this clutter. The curators demonstrate convincingly how the monotypes were specific in inspiring the late series of prints.

Degas, with brutal honesty, depicted all of those smudgy snatches. Picasso, however, ups the anti by transforming them into gaping, snarling caves and swamps of sexuality. They vividly evoke vaginas dentata. It implies that Picasso both lusted and craved women but they also terrified him. Particularly in his old age when impotence transformed his sex drive into deranged fantasies.

In this series he depicts Degas as a visitor to the brothel. But the older artist is in fact a signifier and surrogate for his own voyeurism.

What was most curious about this sexually charged gallery was the benign manner in which viewers just shuffled through. While I was bending over examining the work in that compromised posture I glanced and happened to see an adolescent boy next to me. He was also looking but his face was remarkably expressionless. Were I his age the work would give me a terrible fright.

This may be the best exhibition on view in America this summer. See it while you still can.