How Mom Became Dr. Josephine R. Flynn

Middlesex Later Became Brandeis University

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 18, 2017

One on one Mom was a great sport and fun to be with. My annual trip to Palm Beach to drive her home to Annisquam evolved into vacations and adventures. At the time I was a graduate student in American Art and Architecture at Boston University. These were wonderful opportunities to visit Southern cites, sites and monuments I had studied with a fabulous professor, Dr. Margaret Supplee Smith.

On the first such adventure our first night was in Savannah, Georgia. The desk clerk looked at us and asked “Will that be one bed or two.” We were so embarrassed, my goodness.

Savannah was wonderful as were so many other destinations’: The Cloisters in the Sea Islands of Georgia, St. Augustine, Daytona Beach, Jacksonville, Williamsburg, Charlottesville (in the news this week) Atlanta and Athens Georgia, Charleston, Raleigh, Richmond, Jamestown (and Carter’s Grove), Washington, D.C., Philadelphia.

When possible we stayed at the best hotels and visited the finest restaurants. For lunch I would often go far off road to find barbecue pits.

There was a routine when we stopped at night. The first thing was to fetch a bucket of ice. With the mantra of “Bar’s open” we enjoyed martinis. Mom would rattle the ice in an empty glass and ask for a ‘dividend.’ This is a habit she acquired when traveling. It was cheaper to have a cocktail in the room than in the restaurant.

When Mom and Dad retired they went on a number of medical trips to exotic destinations. There were cocktail parties in the rooms. During a flight to Brazil, her friend, Betty Keane said “Jo, swipe a knife off the tray so we can cut the cheese for our cocktail party.”

That set off the alarm and Mom, a person of interest and possible terrorist, was taken to a room and strip searched. Just the thought of that, as with so many of her anecdotes, just makes me howl.

As the oldest daughter of the oldest daughter of the Nugent clan, arguably, Mom was the first, not only to graduate from college, but to attend medical school. Today it is the norm for women to practice medicine, but in the 1930s it was rare.

In this chapter excerpted from the book I asked what inspired her to study medicine and the challenges that entailed.

Charles Giuliano What happened to the family during the Depression?

Josephine Rita Flynn I think we lost pretty much everything then. He (my father James Flynn) called your father and wanted to borrow a couple of thousand dollars for his liquor license. They were quite expensive as there was a lot of graft under the table. There were only so many licenses. When new politicians came in things changed. I know that Dad (James Flynn) never voted from our Gardner Street (Allston) home. He always voted with the Hotel Osborne as his residence. That one vote meant something to someone running. That's how it was. There was Tammany Hall in New York and I don't know what they had in Boston. Voting was always a big day and Dad dressed up. He got into his best suit with spats. He had a chinchilla overcoat with a velvet collar. When you went in to vote you would see all the politicians around and nod your head. He wouldn't really talk with them he was kind of a distant man.

Arthur (Flynn my uncle) is kind of tight lipped. But if he starts talking he never stops. Like Dad. If he got you he held you and held you and held you. Arthur is just like him. There are a lot of similar qualities.

We had nothing. If we had $2,000 that was every single penny we had to our name. Your father said, Mum, it's your Dad. Go down to the bank draw it out and send it to him. Dad sent him the money and my father paid him back with interest. He was proud as a peacock when he paid the money back. He said "Here Charles and here's your interest." Of course Charles didn't ask for interest. We didn't have enough money to know what interest was.

CG That was the 1930s. What places did your Dad have then?

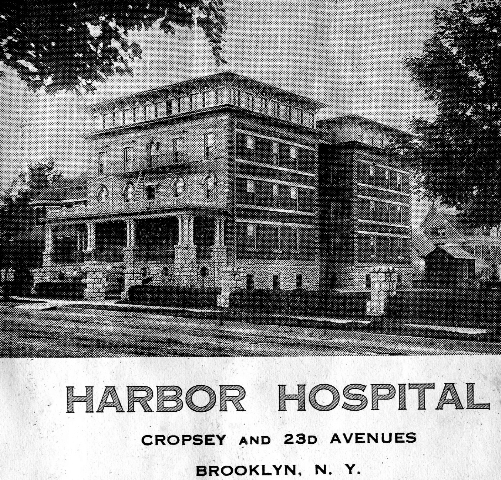

JRF He had the Shubert Grill. Arthur ran the Shubert Grill when he was in (Boston College) law school. (Later he was appointed by John Kennedy to the Federal bench.) He may have had the Silver Dollar Bar on Washington Street. I'm not sure. I was away as an intern and then living in Brooklyn. I had gone to Harbor Hospital on Coney Island to intern in 1932 so I wasn't around. We were married in 1933. So it had to be the early '30s when my Dad asked for a loan and we were really poor. Not just us, everyone was poor. The whole country was poor.

People who have never lived through a depression don't know what it is to be hard up. I remember we had a hurricane in Boston and Arthur went out and shingled roofs and repaired buildings. The hurricane was a godsend to make some money. At that time you paid five cents for a loaf of bread and twenty five cents for a pound of hamburger.

We got paid three dollars for a house call and two dollars for an office visit when we first started practicing.

(Later when I was a kid and they practiced in Brookline in the 1950s she got $15 for a house call and $10 for an office visit. Unlike today physicians actually spent time with their patients. As a family doctor Mom often heard their troubles and functioned like a priest or shrink. Her practice largely focused on obstetrics/ gynecology and pediatrics. Mom and Dad treated many family members. Dad's relatives came from Brooklyn for operations.)

When your Dad and I went on that first date doing home operations we were paid $25. Everything was done in the home in those days. Getting $25 for a delivery was big money. That could take all day. When I arrived and they were shrieking and screaming I just stayed there.

After office hours Dad and I would go out. There were some nice places and we would have a snack and beer. We thought it was wonderful. I don't know if it is better than today's beer or not. Beer is beer. We would have sandwiches and clams on the half shell. They were a penny apiece. Raw clams, ooh, with lemon and hot peppers. Oooooh were they good. Even today I love raw clams and clams casino are my favorite. Then we would go to the movies for twenty five cents. In Brooklyn you could sit in the balcony and smoke during the movies.

There was a place near the Adelphi Hospital where you could sit on the roof.

CG Tell me about Brighton High School. You were a smart student.

JRF No. Just average. For grammar school I went to Washington Allston. We had a student council and there was a mayor who was head of the council. Naturally, I ran for mayor instead of for the council and I won. We had to decide on students getting demerits and assigned to detention after school. We would issue the punishments.

CG Didn't you get to be Mayor of Boston for a day?

JRF Oh yes. Under Mayor (James Michael) Curley. He invited me and the whole council to (the old) City Hall. They took pictures of us with Mayor Curley. I sat at his desk. We sat in the Council room and listened to the proceedings. He gave us signed books of his speeches. I would give anything to have them today. But the promises he made in those speeches were unbelievable. Even a child could see through them. You couldn't believe the promises he made. Even Reagan with his tax cuts, you know damned well we're not going to get them.

(James Michael Curley, November 20, 1874 – November 12, 1958, served four terms as Mayor of Boston including part of one while in prison. He served a single term as Governor of Massachusetts. Curley was the fictional character in The Last Hurrah, a 1956 novel made into a I958 film by Edwin O'Connor. Spencer Tracy starred as Frank Skeffington.)

CG Did your father play politics?

JRF No, he didn't. Things might have been different if he had. He always voted the Democratic ticket.

CG Today you're a Republican. In those days if you were Irish you were a Democrat.

JRF That's about the size of it. I have always voted as an independent.

CG Back in the day your father's family were on the run from the troubles in Ireland when they settled in Canada. They made their way from New Hampshire to Rockport as quarry men.

JRF Of course there were a lot of Irish politicians in Boston and they helped their people and immigrants. Then there were the old Yankees who never gave them the time of day. It was a house divided. Being Catholic or Protestant in those early days was a strong line of demarcation. There was a street you would never cross.

CG You dated Protestant boys.

JRF Things were changing by then. Back in Rockport, when my mother was a little girl, they burned down the Catholic church.

CG You're kidding.

JRF No, I'm not kidding. They burned the church down. Yup. They couldn't stand the Irish. But they were smart people and they came up. How many years ago would the Italians and Irish get together? How many years ago would Jews get together with Catholics? Things have changed.

CG Were you smart?

JRF Not really. Were you smart? The report cards didn't say so.

CG I went to Boston Latin School.

JRF I had four years of Latin. I had algebra and trigonometry and chemistry. I didn't have physics. Why did I become a doctor? My father's influence. He went to the world's championship fight. (Jack) Dempsey and (George) Carpentier (July 2, 1921, Jersey City, New Jersey). He took my mother with him. I went to all the championship fights in New York with your Dad. He loved the fights. I saw the Brown Bomber. I saw them all.

They came back from New Jersey and brought us all a present. My present was a small picture of a doctor sitting by a patient. He wrote on the back of the picture "To our future doctor, Jo."

That picture was a huge inspiration. Who painted that picture?

CG I don't know. But I know the painting you mean. (Sir Luke Fildes "The Doctor" exhibited 1891)

JRF With Arthur he talked politics and current events. He just wanted Arthur to be a lawyer. Arthur said he would have liked to have gone into medicine but my father's influence was enormous.

Dr. Emerson came in and listened to Brother's heart. They didn't find anything but he had a leaking valve and is still living to this day after the war. Maybe it was a little anemia, a hemic heart murmur or something. My mother said to Dr. Emerson “Josephine is going to be a doctor." He threw it down. A woman! You have to be away and everything. The worst thing in the world to have a little girl thinking of being a doctor. That made me mad. It made me want to study more than ever. What right did I have to even think of studying medicine?

It's little things like that influencing you in your life. At the time you don't realize the impact.

CG Nobody was pushing you.

JRF Nobody. It was destined to be. Dad would never consider me being a housewife. When we got married and went to the court house I expected to change my name. He said, no, you keep your own name. I'm Dr. Giuliano and you're Dr. Flynn. We have the same kind of practice and the same patients. You keep your name. We would be introduced somewhere and he would say "I'm Dr. Flynn's husband." He thought that was funny. It was better.

CG You graduated from Brighton High School.

JRF Washington Allston was the name of my grammar school. He was a famous painter. Then I went to Brighton High School. When I graduated I wanted to study medicine.

CG Why?

JRF (with emphasis) Well, I don't know. It was a calling inside of me. There was a little 'beep beep' that said 'You're going to study medicine.' You want to be a doctor. It was just one of those things. It was a spiritual thing, a calling. You can't describe it. Like the priesthood or a convent. It was a calling.

CG You went to Tufts.

JFR Yes, I went there. But I didn't make out great. I lasted a year. It was very scientific. It was laboratory all day long and experiments. It was premed with chemistry, physics, and English composition. You had to write every single week. It was very taxing. Unless you're really great in science.

I met Bob Carmody at Tufts and we became friends. When we left Tufts he found out about Middlesex (College of Medicine and Surgery). I was the only woman at Tufts. It was very difficult. Coming from Brighton High School I didn't have the background in sciences. Had I gone to a prep school I don't think I would have had any difficulty. But at Brighton High School the teachers were of very poor quality.

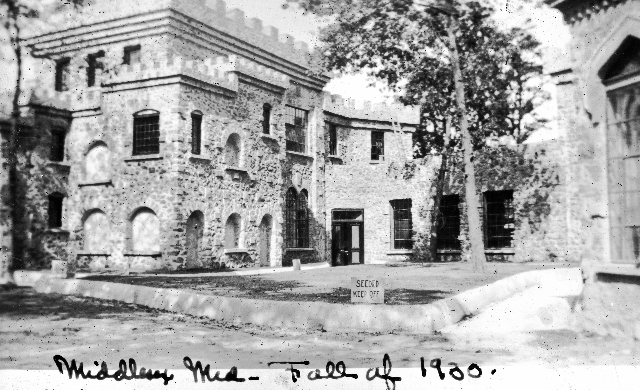

We applied to Middlesex and took premed there. At the time they were located on Newbury Street. They had a hospital in East Cambridge where we observed operations in the amphitheatre. The medical school, I believe, was on Beacon Street.

The first day I witnessed an operation we went out to lunch, on a Saturday, and I had a liverwurst on rye sandwich. I can remember because to this day I can never eat a liverwurst sandwich again as long as I live.

They wheeled the patient in and I watched that scalpel come up and zoom. A little blood oozed out and that got me. Oooh. I was sick. I vomited for 24 hours without stopping. Every time I vomited I could taste the liverwurst. Oooh, to this day just the thought of liverwurst would make me sick.

After awhile, the way they poured ether in those days, you got used to it. You didn't mind it. That just got to be routine like smelling some shaving cologne. In the beginning it was very difficult to get used to the smell of ether.

That first time was rough but it's like falling off of a horse. You have to get back on.

CG Why study to be a doctor? You could have become a nurse.

JRF Oh no. A nurse is harder than being a doctor. You go in and see a patient and examine them as a doctor, and cheer them up, you may feel sorry that they're dying, but you walk out. If they're cranky and cantankerous, you walk out. But a nurse is sitting there for eight hours. She can't leave them. Of course today it's different the nurse is at a desk or station and not sitting with the patient.

As a doctor you did what you could do, the glamorous part, and then left them. The nurse's job is very difficult.

I wasn't destined for that. The little calling inside the fairies weren't telling me to be a nurse. The fairies were telling me to be a doctor.

CG Tell me about Middlesex.

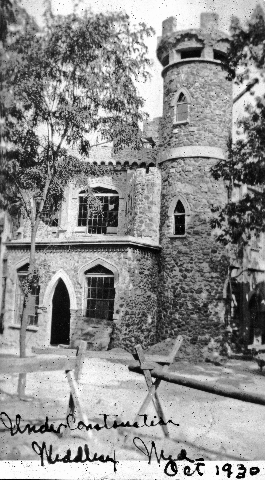

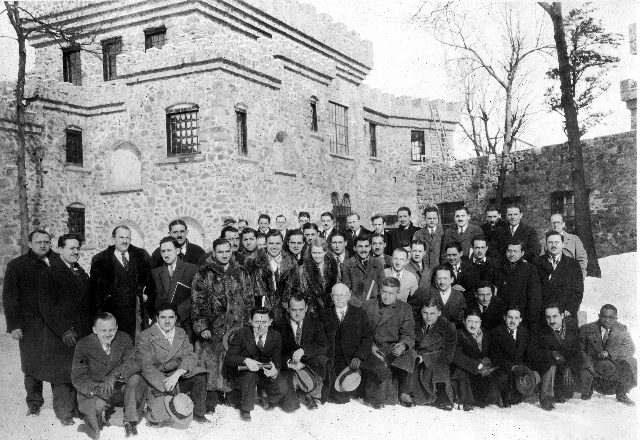

JRF John Hall Smith was a very brilliant surgeon and a very dignified man. He had grey hair and a little goatee. He was unapproachable. He was a god of all that he surveyed. While I was there he had a dream and built out in Waltham a medical school which is now taken over by Brandeis.

I did two years of premed and then four years of med school. That's how it worked at the time. My first year of med school was in Waltham. Most schools at that time required four years of premed and four years of med.

My first year the Castle and Tower were brand new with no heat. It was maybe 1928. He designed it and it was made out of field stone. We were so thrilled to be out there with those big classrooms. No heat. We just wore our coats and gloves all day. One day toward spring we heard the pipes cracking and there was heat. Ooh, we were thrilled. But we accepted it.

There were about 200 students and maybe fifty in each class.

CG Was John Hall Smith a wealthy man?

JRF No. I don't think he was. I think he spent every cent he had on the school.

CG Did you ever see him operate?

JRF Oh yes. In fact he operated on me when I was in high school. I had a ruptured appendix. When I was young I would get attacks of vomiting. It would last a couple of days and I would be very sick. Then it would clear up and I would be fine. There was a question at some point, does she have appendicitis?

I was a senior in high school and I had one of those attacks. They rushed me to the hospital by ambulance and Dr. John Hall Smith operated on me. Looking back I think I was a very fortunate patient because he was an excellent surgeon. I was very fortunate to have a man of his caliber operate on me.

CG Was he a general surgeon?

JRF Yes. His son, C. Ruggles Smith was my English teacher. He never talked above a whisper. He was very soft spoken. You could hear a pin drop on the floor because he got such attention. He taught The American Novel. We read all the classics. I enjoyed that class tremendously. We read about the stockyard. (Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, 1906). The one about the girl that was drowned. What was that? (Theodore Dreiser, An American Tragedy, 1925) My memory isn't so good today I can't think back. But we read them all.

(When John Hall Smith negotiated the transfer of Middlesex to the founders of Brandeis he had a condition. The university would provide his son with a tenured position. When I later applied to Brandeis the admissions director was C. Ruggles Smith. Mom was with me. He told me to take a walk around the campus while they caught up. Later that afternoon I was admitted to the class of 1963. From stories she had told me the Castle was always very special. As a senior I had a private studio there and painted a mural in a secret room above the entrance arch.)

CG Were there women in you class at Middlesex?

JRF At times there were. There was an Italian girl. She was in my class maybe only for a year. Mildred something. In my junior or senior year Dorothy Vohr came in my class. Her name was Dorothy Larsen at the time.

We had a man in our class who was a dentist. He graduated from Tufts Dental School but he wanted to be a doctor. He had had anatomy before. We had cadavers which you had to fish out of the formaldehyde vat every day. We would pound our feet now and then because it was so cold. If the professor didn't show up this student, who was a former dentist, would conduct the class.

CG How often didn't they show up?

JRF It was quite often we didn't have teachers. But we would get out our books and form study groups. We were there to learn.

CG How did you get out there every day?

JRF I lived at home in Allston. For the most part Bob Carmody drove me. Some days I took a streetcar, oh, it was wicked.

One teacher who never failed to show up was Dr. Campagnia. He taught pharmacology. His class was at 8 AM on the dot and at one minute past eight he locked the door. If you had so many cuts you flunked the course automatically. So I can tell you he always had 100% attendance. He was excellent.

For the most part the doctors that taught there worked for love. I doubt very much they made any money. We had to work hard for what we got. If somebody didn't show up for a class we didn't goof off. We closed the door and somebody would conduct the class. We would council and review each other. We didn't want to miss that hour and took it upon ourselves to have an open study hall. We fired questions back and forth. We didn't goof off and smoke cigarettes or anything like that.

CG Did you have a social life?

JRF On Saturday nights I went out. You wouldn't go out during the week. That was an unwritten law.

CG Who paid your tuition?

JRF Dad, naturally. At that time it was coming to the Depression and tuition was expensive. But he never complained. When it was due I would say I have to have my tuition on Monday Dad and it would be right there. Dad was never a day late. I would say, a new semester is going to start, and give him a little leeway. This was coming into real Depression times.

Everyone brown bagged their lunch and we never left the campus.

CG When did you graduate?

JRF I graduated in 1932 but my diploma says 1933. At the end of our senior year John Hall Smith said that anyone who wanted it could have their diploma. But he advised that we take a year of internship and then get our diploma. You weren't qualified to take the state boards without a diploma. If you delayed for a year you were more mature and had more practice.

Only one student, Moriarty, took his diploma. He took a shot at the boards and passed them. He was the only one out of the whole class.

CG What became of the Middlesex doctors?

JRF They went all around. I would see them at meetings. For the most part they were very industrious people. They worked hard and achieved positions and dignity in life. Very few of them went astray. They were sober industrious men. Most of them came from poor families and really wanted to work. In my class everyone took the state boards and was admitted to practice. If they had a little political pull they went to different states.

CG Did you see patients?

JRF Yes, we had the hospital in Cambridge. During the summer time I want to Boston City Hospital. My first year I worked in the venereal disease clinic. I gave IV injections of selvafan and intramuscular shots of mercury. That's how we treated syphilis. They would be lined up. We would give maybe 50 IVs in the morning. We had a big tray with alcohol and syringes all lined up.

Another year I spent in the dermatology department. The third year I spent in the medical department; internal medicine, heart, blood pressure and so forth.

I was an extern which is like an intern without living in the hospital. It's lucky we had a place like Boston City Hospital where we could get work. I was very lucky that I applied there and was accepted.

CG What became of Dorothy Vohr?

JRF She graduated and settled out in Lee, Mass. She married Freddy Vohr who was a class ahead of us.

CG She died young.

JRF Quite young. I'm not sure she was maybe 60.

CG Was she a good friend?

JRF Yes and no. I was always scared of Dorothy. She interned with me. If Dorothy wanted it quiet you wouldn't dare to breathe. She was a very demanding person. A wonderful person and I liked her. She was generous and good. I went to visit her out in Lee when she was practicing.

There was something and I can't describe it. She was a little hyper. She was the only woman in my class. There were three women in the class before me. There was Rose Saretsky who married Dr. Bill Bowman. She practiced in Western Massachusetts. There were two others but I can't remember their names. They were very fortunate to have three of them together.

It was unusual then for women to go to medical school. (Dr.) Louis Wolfe was saying to me just the other day, "Jo women are almost controlling medicine today at the meetings."

CG From the old photographs you were a rather glamorous young woman.

JRF You're my son so you can say that.

CG Were you a flapper?

JRF I loved Friday and Saturday night. Copley Plaza was a big place to go. The Oval Room.

CG Was Bob Carmody your boyfriend all that time?

JRF I had a lot of other boyfriends. I can't think now. Oh, I had Eddy Henderson who went to Harvard. Then, oh, Ryan, I can't think of his name.

There was the old Brunswick Hotel on Huntington Avenue in Copley Square. That was a great place to go on Saturday night. They had an orchestra for dancing. Then there was Shepherd's Department Store across from Park Street subway. They had tea dancing on afternoons during the week.

CG Did you go to the Ritz?

JRF It wasn't in existence then. It was built a little later. The Statler also came along a little later. I had a nice social life. Do I regret my social life now? I don't know. Of course when it came time for final exams we made up for it. Then you had to make up for those Saturday nights. We really taught ourselves all of the courses. We would take a month and for that month we would stay up all night long. There were maybe five or six or us in a group.

They would come to my house and we would study in the den. When the sun came up we would quit. Take a nap in the afternoon and get ready for the evening. We went through course after course. We wanted to pass didn't we? Then we would say, oh, if only I had studied like that through the year. If only we had worked that hard we would have been geniuses.

CG So it wasn't an easy school.

JRF We couldn't allow it to be easy. We had to pass exams, earn a diploma, and qualify to take and pass the state boards. We had to discipline ourselves as students to work and study. The doctors who came and taught they didn't care if we flunked or not. It was our life that mattered. It was up to us. If the course was bad we had to make up for it. We had to work twice as hard to dig it out of the book. Chapter by chapter ourselves and go over it. Nobody was spoon-feeding us. You had to work very, very hard to make something of yourself. No goofing off.

It was a long trip out there to be in class at 8 AM every morning.

CG After graduating in 1932 where did you go for an internship?

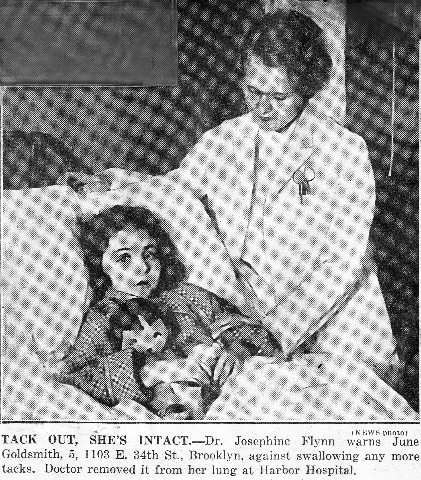

JRF Out on Coney Island at Harbor Hospital. I applied and at the time they didn't have quarters for women in hospitals. It was tough and I was getting despondent. I was writing to one place after another. It was difficult. They had quarters and baths for males but none for women. Finding a place that could house a woman was a little different. I was desperate for awhile during that summer. I was depressed writing, writing, writing. When I got in I was so happy.

In the beginning I rode the ambulance.

CG Did Dorothy Vohr go there as well?

JRF She went before me. I'm not quite sure. Then she left before me. She finished before I did. She got in and then said "Jo there's an opening for you." I think that's how it went. I was two years there.

I had my own quarters and lived in the hospital. I got fifty dollars a month as pay. That was rich. Now of course interns make about $22,000.

You were initiated on the ambulance. I think I got down there on July 4th. The old ambulance drivers, they were nice men. They knew the tricks.

The police would call in. The office would stamp the time clock. You would have so many minutes to get on that ambulance. You would pick up the slip and punch out. The slips were kept to document the time in and out. You would get in the ambulance and a police car would always follow. The accident or whatever it was they would be there too.

Today, we have a more or less socialized medicine and people go to the emergency room. In those days they couldn't so people called the ambulance for lots of foolish little things. Some times for sick children or this or that. I was on 24 hours and off 24 hours. The 24 hours you were off you covered the emergency room and did rounds and wrote histories.

You had one day a week off. If you went out on Sunday and came back at 11:45 PM at twelve you were on duty. It wasn't easy kid (laughing). Not like today. You were young and recuperated quickly. You could grab naps. You were in uniform with one eye open and a foot on the floor because the minute that phone rang you had to hustle. You had to run to punch the clock. I don't know exactly but I think it was two or three minutes we were allowed.

It was part of life and you accept it. For a woman or a man what was the difference? I was a person right? You had no privileges being a woman. They expected more of you because there was an antagonism about women. They were looking for a slipup, a little something that you did.

The first time I went out the driver's name was Flynn. He was a nice man. Somebody had an acute asthma attack. In those days they didn't have cortisone. I knew you gave them adrenalin. I had it in my bag so I poured out a teaspoon. Then off we went back to the hospital. Driving back old man Flynn turned around and said "Dr. Flynn, you give it by hypodermic needle. And you give so much." Sure enough, five minutes later we got called back because the adrenalin isn't working. So now I am very sophisticated so I wipe off the top of the bottle, stick the needle in, and give the patient a shot of adrenalin. It worked. All I knew is that you gave adrenalin but how you administered it I didn't know.

Once in awhile those old timers could tell you little tricks. They would say give them this or give them that.

One night I got a call to go to the police station. An addict was shrieking and screaming for morphine. The captain said "Go in the cell and give him a shot." I thought this is awful, ridiculous, go in the cell and give him a shot? Leading to his addiction? Oh no, no, I won't give him a shot. I'll give him a shot of water but I'm not giving him a shot of morphine.

We went back to the hospital, I was lying down, and zoom, we got called back. The police captain said, "Look, Doc. We want peace and you want peace. The only way we get peace is give it to him." I gave him a shot to keep him quiet. After that you would say "What do you take? What's your dose?" It became a routine thing. They would bring in addicts arrested for something; stealing, murder or rape. They would shriek and knew that in the police station they could get it because the police wanted peace and quiet.

A normal dose would be a quarter of a grain but if they said two you would give it to them. Otherwise you would be called back again and again.

We did a lot of deliveries in the homes.

CG What if there were complications?

JRF Throw them in the ambulance and take them to the hospital. When we got there you had a little kit in a pound candy box. There were clamps and what you needed, a little thread to tie off the cord. That was your OBS kit.

Anything you couldn't handle you'd bring in. But before you would go they would say "Don't bring us any surgical cases we don't have time tonight. We're busy and all booked up." So we would take those cases to another hospital like King's County.

You learned a lot. You had to think quickly. It was practical experience but a lot of it was wasted. It's repetition so you never know. I had no fear as the police were there. Once in a while they would say "Doc would you like a drink of beer?" Along the strand there on Coney Island we always stopped and got a (Nathan's) hot dog with sauerkraut no matter what time we went by those places. They were good, oooh, good. We would take a few minutes and have a snack on the run.

People would cut themselves on glass when walking on the beach. The ambulance would come and a crowd would gather around. If it was just ten stitches you just did it there. Any more than that you would bring them in. No Novocain, not sure we even had it. There was no pampering ambulance patients. The idea was to just get it done.

One time a woman had been scalped. In those days they had wire clothes lines. She bumped into the clothes line right above the eyebrows. The whole scalp came right back off her head. We took her to the hospital and they sewed it up. They did such a good job you couldn't even see it.

CG Did she survive?

JRF Oh sure. That was nothing. It was just a scalp wound. Now I can see what the Indians were doing. It was very easy. Comes right off.

Dorothy Vohr was stitching somebody up on the beach. They were crowding her. She kept shouting step back, give me room. She had a temper which was why I liked her. When she got fed up she dipped a swab in the mercurochrome bottle then whirled around and sprayed the crowd. That took care of it.

Gloucester Poems: Nugents of Rockport, 375 pages, illustrated, $20 may be purchased through Amazon.