Women Artists in Paris, 1850-1900

Revisionist Exhibition at Clark Art Institute

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 16, 2018

Women Artists in Paris, 1850-1900

Clark Art Institute

Williamstown, Mass

Through 3 September, 2018

Women Artists in Paris, 1850-1900, is an ambitious, scholarly but problematic exhibition at the Clark Art Institute. It has been drawing large crowds and ends on 3 September.

The premise of the project is that, not just French women, but aspiring artists from Europe and America came to Paris for training that was then rare. As an extensive catalogue relates there were many obstacles to overcome. These were social, economic and familial. Women were generally denied legal status and independence.

While creating art was an acceptable avocation the glass ceiling of professionalism was formidable. It helped, if as in the case of the American artist Mary Cassatt, one was unmarried with independent means and social connections.

Those factors made possible her career and she advised American visitors on which emerging Impressionists to acquire for their collections. That contributed to the great holdings of major museums in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago.

Among the most successful women artists are those who, at the time, were described as “painting like a man.” Or in the case of Rosa Bonheur, the most renowned woman artist of her generation, lived openly in a “Boston marriage” and dressed in primarily male attire. A painter of animals she had special permission to sketch in slaughter houses.

During the Ancien Regime young women of the court were diversely tutored in the arts. This entailed skill at music, dancing, conversation, sewing, sketching, water color and decorating fans. These were assets that she brought to marriage and their salon. A well set table and successful evenings advanced her husband’s social status and career.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (16 April 1755 – 30 March 1842), who managed to avoid the guillotine, was a widely traveled portrait painter. A famous portrait of Marie Antoinette with her children hangs at Versailles.

There were isolated examples of successful women artists that predate 1850. This is an area of scholarship and most art history programs offer courses on women in art. The standard survey texts, like Janson’s History of Art and Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, have been revised and new more integrated texts have emerged.

The Clark project, among the most in depth examinations of this period, is best regarded within this purview.

There was a mix of both well known artists such as Berthe Morisot, Cassatt, and Bonheur as well as many lesser known artists. Of particular interest were several Scandanavian women who studied in Paris and convey a different, engaging and even haunting Nordic sensibility. When they returned home, with techniques learned in Paris, they were shunned by a generally conservative culture.

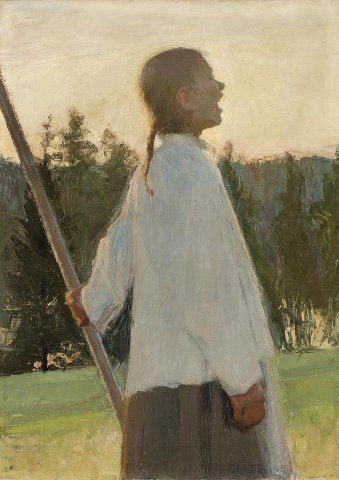

One such progressive work is “Echo” (1891) by Ellen Thesleff (Helsinki, 1869-1954). It depicts the profile of a young girl at twilight. The treatment of her face has the low chroma of that time of day. In a sketchy, proto expressionist manner, she appears to cry out for unknown and evocative reasons. The work is so singular and engaging that it is the cover of the catalogue and has been blown up for outdoor signage.

It is always fascinating to see works by Paula Modersohn-Becker (German, 1876-1907). Influenced by Les Nabi her generally small works distort the figure in a manner that initially is unappealing. In the context of this survey of primarily pretty pictures most visitors will hardly pause before her work. She is, however, one of the most unique, poignant and fascinating artists in this survey. Although she died young after complications of a difficult childbirth, in fourteen years, she left a legacy of 750 paintings, 13 etchings and approximately 1,000 drawings.

There are still life and landscape paintings but the curators opted to show a small sample. These were the most common subjects of women of this period. Given the general social restrictions of women their figurative art focuses on mothers, children and a woman’s world.

There is little of what Charles Baudelaire, the leading critic, admired in the work of the flaneur, Constantin Guys, Ernest-Adolphe-Hyacinthe-Constantin, (December 3, 1802 – December 13, 1892) the “painter of modern life.”

That was the domain of Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. On the fringes of their depictions of modern life were Cassatt and Morisot. These well heeled women were a part of the inner circle of the most progressive artists. She and her sister Edma were shown in the official salons. Berthe was painted several times by Manet who by then was secretly married. Berthe married Eugene the artist’s brother. Edma, a promising artist, quit painting in deference to her husband.

Morisot’s self portrait with Edma, “The Sisters,” 1869, is a finished work that evokes Manet’s formal, realist style. It contrasts with several loose, sketchy paintings in the exhibition that are in an impressionist manner most resembling the figuration of mid-career Renoir.

It is unfortunate the curators did not research and include the admittedly rare work by Manet’s notorious model (“Olympia” among others) Victorine Meurent (1884-1927).

There is a tradition of models, who spend so much time in the studio, taking up painting with informal instruction from their employer. Manet is said to have regarded her as more of a collaborator and muse than just model. There is interest in her wider role.

“In the late 20th century, scholars discovered she had, in fact, lived until she was 83, spending much of her life productively as a painter in her own right. Even so, the details are sketchy. The woman who helped inspire some of the most iconic images of the 19th century still remains an elusive figure.” Kathryn Hughes

“In the early 1870s, she is believed to have travelled to America, perhaps engaged by an art dealer to accompany some paintings. By 1875, she had returned to Paris and was attending evening classes at the Académie Julian. Her self-portrait was shown at the Salon in 1876, and after that her work appeared there in 1879, 1885 and 1904. In 1903 she was elected a member of the Société des Artistes Français...

“The painting acquired by the Musée Municipal d'Art et d'Histoire de Colombes is ‘Le Jour des Rameaux,’ which shows a young woman holding a palm leaf, and leaves one in no doubt that it was painted by an accomplished artist.” V. R. Main, The Guardian, 2 October, 2008.

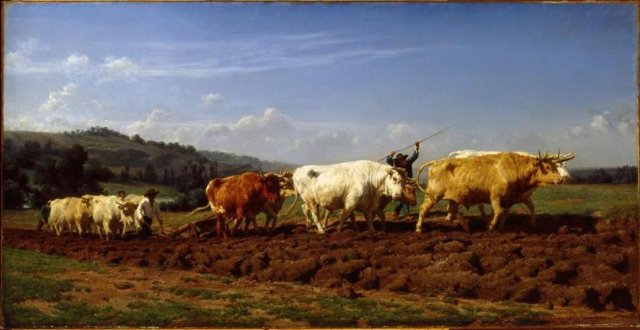

The career of Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822-1899) requires no reclamation. A specialist in animal subjects she was a successful salon painter. Her vast canvas “Plowing in Nivernais” is the most dominant in the exhibition. In clear, brilliant light we see every hair on the hides of two teams, six each, of oxen. The pastoral subject evokes Barbizon painters but it is less metaphoric, more epic and stridently naturalistic.

Taken out of the context of when it was created one might wax poetic about farming on the cusp of the industrial revolution. A generation ago, when we were taught an antipathy to academic art, one was more inclined to snicker than admire. Her enormous “The Horse Fair” has long been a favorite of visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A major museum exhibition of her work is overdue. In 2015 there was a small one in the rural Musee de Vernon.

Raised on theories of modernism one took the side of the impressionists and their Salon des Refusé. For almost a century the pompier artists of the salon devolved from pride of place to the basements of museums. Revisionism began in 1975 when an abandoned train station was transformed into Musee d’Orsay. The curators opted to give equal billing and space to opposing factions of 19th century French art.

That continued with the publications and exhibitions of art historian Robert Rosenblum. With H.W. Janson he wrote what has become a standard text “19th Century Art.” They devoted equal treatment to conflicting factions and expanded the dialogue beyond School of Paris to embrace Northern European and Russian art. It is an unwieldy text for teaching the period.

“Mr. Rosenblum reveled in what he called ‘the messy mix’ of high and low.” Grace Gluck wrote in a NY Times obituary, 9 December, 2006. “That approach was also evident in the Guggenheim’s ‘1900: Art at the Crossroads’ in 2000, an exhibition intended to convey a broad sense of what was being painted throughout the world when the West was on the cusp of Modernism.

“The museum displayed 150 paintings from the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris with examples from Japan, the Americas, Africa and Australia, as well as works by onetime Salon idols like Adolphe-William Bouguereau and Lawrence Alma-Tadema and recognized founders of Modernism like Cézanne, Picasso and Kandinsky. ‘I wanted to reshuffle the deck and re-examine our image of the period,’ Mr. Rosenblum said at the time.

“Reaction was mixed. ‘It is hard to remember the last time so many bad pictures were in one place at one time, unless you consider eBay a place,’ Michael Kimmelman wrote in a cautiously positive review of the show in The New York Times. Citing the inclusion of such little-known artists as Eugene Jansson and Eugène Carrière, Mr. Kimmelman added, ‘The show provides compensatory rewards for its schlock quotient.’ “

Work by Adolphe-William Bouguereau is on view in a group show this summer at the Norman Rockwell Museum. Last summer, the Clark mounted a major show of Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

If, as Kimmelman suggests, the kitsch paintings of Bougereau represent the schlock quotient then how to react to paintings at The Clark by his wife, Elizabeth Jane Gardner Bougereau? The best that is said of her is the extent to which her paintings resemble his. Which isn’t saying much. The Clark owns Bougereau’s hilariously bad “Satyr with Nymphs.”

Unfortunately, with exceptions here and there, the women artists on view at the Clark emulated the fashionable artists of the day. So we are viewing second and third tier popularism.

It takes a discerning eye to separate wheat from chaff.

In the manner of patriotic potboilers by Ernest Meissonier, and before him Jacques Louis David and Baron Gros, Britain’s Lady Elizabeth Butler aspired to epic military themes. Arguably, from a woman’s perspective, we see the aftermath of “Balaclava” 1876.

Here and there are stunning works. A large painting by Louise Abbema “Lunch in the Greenhouse (Le Dejeneur dans le serre)" 1877 has a complex composition of six figures and a girl arranged around a table. The clear and precise chiaroscuro evokes the Spanish style of early Manet. With a smile and long white day dress the artist converses with the child. Stretched out and partly obscured behind her, head propped up by an arm, lounges the actress Sarah Bernhardt.

The work of Marie Bracquemond is described as significant. Her approach to impressionist technique, however, is dense and overworked. The broken brush stroke does not allow for transparency and light. She is admired for depictions of bourgeois women but her “Three Women with Parasols (Trois femmes aux ombrelles, Les Trois graces),” 1880, is a dense, opaque disaster. It is a labored of love.

Some of the genre paintings are absorbing. We see urchins clustered and wonder what mischief they are up to in “The Meeting,” 1884, by Marie Bashirtseff. She also created the evocative “In the Studio,” 1881. It depicts a cluster of women at work painting a young boy staring out plaintively. Leaning on a long staff he wears a loose cloth around his hips. That’s as close as women got to painting the nude figure. The artist died of tuberculosis at 25.

There is an interesting glimpse of village life that evokes the novels of Flaubert in “The Marriage,” 1884, by Julie Delance-Feugard. The veiled bride and groom pass by in the background. Close to us two women gossip and a distracted girl holds the center of the composition. The painting is curious and droll.

What this show craves for more of is the brilliant color and light of “The Harvesters,” 1905, by Anna Ancher (1859-1935). The small canvas by a Danish artist has a starkly geometric composition. The lower horizontal half depicts mature yellow wheat. The upper half in profile has a farmer with scythe and two women one with a rake. It’s a delightful picture.

The exhibition of 70 paintings was organized by the American Federation of Arts and curated by Laurence Madeline, Chief Curator for French National Heritage.