Lost but not Forgotten

"Vanishing Point": Photographs by Shuli Sade at Kolok Gallery, North Adams, MA Aug. 12-Sept. 6

By: Jane Hudson - Aug 13, 2006

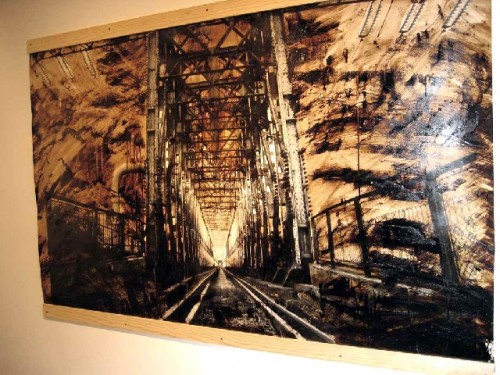

Shuli Sade grew up in Israel. She was trained at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design there, and later became culture coordinator in the Center for American Culture in Jerusalem. In 1984 she moved to New York City, where she now lives, and there began her adventure with architecture. Working for an architectural firm, she joined the Association of Industrial Archaeology where her passion for the abandoned behemoths of the Industrial Revolution was kindled. Devoid of people, these spaces built so formidably for use by people, spoke to her of a suspended time, where light, space and history join in a manifest affect.Twenty years ago, Sade began to experiment with the surface of her photographs. Working first in the darkroom to extract the most nuanced range of light and darkness in the negatives, she began applying tar to the finished prints. Exploring the chemical consequences of this experiment with experts at the Kodak Labs in Rochester, N.Y., she discovered that 'asphaltum', a tar-like substance, could be used with no ill effects to the long-term life of the images. Pouring the material onto the print, waiting for it to 'set', and then scraping, brushing and wiping it across the surface, she was able to give the images a substantiality that evokes the very grittiness and historical distance of the sites as well as of the photographic process itself which is so much part of that Instustrial 'mechanique' about which she speaks.

We see bridges, factories, mills, refineries and warehouses all in heroic scale sited on the land and by the water they affected so completely. These are 'brown' sites, the shameful and baleful residue of the once mighty production of industry. And yet, given the play of light and the vigor of the gesture, they also speak of a kind of beauty, engendered here by a loving and poetic hand.

One is reminded of the Bechers' bleak monuments from Europe's past, recorded so faithfully, as a kind of 'dictionary' of industrial terms. Those unswerving observational recordings allow for little poetry or interpretation as they insist on their formal outlines and demographic specifics. In the case of Anselm Kiefer's grotesquely heavy surfaces, image and object so closely attend each other as to remove any light or air, giving us the definitive accumulation of dying tissues to contemplate.

In the case of Sade's works, we can still enter into the romance that Lionel Feininger saw in the Brooklyn Bridge, an excitement of the possible, here suspended but still evocative as a remembrance and a visual pleasure.

Link to: http://kolokgallery.com