Artwashing: Gentrification or Cultural Enrichment?

Aiding Derelict Neighborhoods or Abetting Social Inequity

By: Mark Favermann - Aug 11, 2016

Political correctness (PC) can range from a demand to be polite to full blown liberal fascism. At times the requirement to ‘do the right thing’ turns ideological, to the point of fostering cultural squabbles. PC has now come up with terms that frame urbanization and community building in resolutely critical ways. One particularly fashionable label is artwashing.

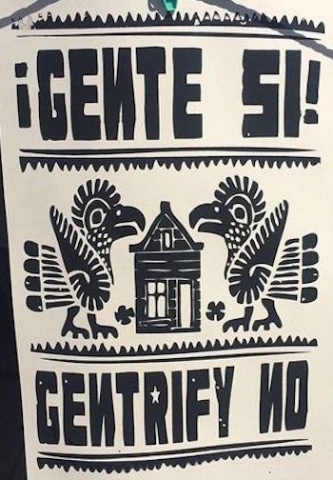

Artwashing could be described as snarky. It is also paradoxical. The term is a pejorative coined by rabid anti-gentrification activists out to undercut the use of artists, galleries, performance spaces, and cultural institution satellites to rejuvenate a derelict or deteriorated neighborhood or community.

It is well-known that, working with very little, artists can serve as creative urban pioneers. To most rational-thinking individuals it seems to be a rather good idea to bring them into degraded urban areas. But there are those who condemn artwashing as community–destroying. To the mind of these critics, cultural infusion exacerbates class differences, encourages unwanted neighborhood changes, and even takes advantage of undervalued artists.

Artwashing has also come to mean a strategy that corporations, through the financial support of cultural activity, use to take care of image problems. For example, the sometimes environmentally bad-behaving (2010 American Gulf Coast Oil Spill) BP sponsors the Tate Modern programming at the Tate Modern in London. In this way, public relations and marketing fuse with high profile cultural generosity to assuage corporate guilt. Or at least to airbrush public perceptions of villainy. This diversionary tactic of the powerful dates back to at least the Renaissance.

In both of its senses, the term is used as a negative but, and it is a very big but, there is also a cultural good being done by bringing the arts into urban communities. To skeptical neighborhood activists and self-righteous academics, the social/economic health of a community is abused if its original residents and businesses are changed, displaced, or somehow marginalized. Any attempts at progress or financial evolution are equated with the sin of gentrification.

Naysayers resent what they see as the patronizing cultural overlay, arguing that the community will be radically transformed, housing prices will go up, the poorest in the neighborhood will be displaced, etc. They brush aside the hope that the community will be revitalized, becoming more diverse, safer and, if done right, experience an improvement in its quality of life. In an urban design and planning sense, a cultural blanket is a very warm way to generate progress of all kinds.

Critics’ often specious argument is that artwashing turns artists and members of the larger creative economy into co-conspirators, part of an insidious and treacherous scheme to infiltrate the community. Instead of viewing the arts economy as part of a beneficial urban planning tool, they see artwashing as no more than a feel-good expedient, a pretty but thin curtain that dresses up a formerly neglected area in order to rebrand it as highly desirable for the upwardly mobile — think what has happened in several neighborhoods of Brooklyn, NY.

Activists in deteriorated neighborhoods in both the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights and in the East London neighborhood of Shoreditch have recently strongly pushed back on community art and cultural enhancement.

The counterargument to this is powerful. For those who discount the impact of cultural planning as a tool for revitalization, just look at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain and the Tate Modern on London’s South Bank area. Both projects placed vital institutions in derelict sites — they are now powerful magnets for social and cultural activities. Each institution has enriched its environment far beyond the bottom line introduction of art or the creative economy.

In terms of Boston, the once mostly derelict South End of Boston was slowly revitalized, over a 40 year period, into a prime residential neighborhood. The Boston Center for the Arts, the Boston Ballet, and the Calderwood Pavilion theatre complex have added to a vital economic mix.

A few blocks away, a planned visual arts sub-neighborhood, SOWA (South of Washington Street) has taken about 20 or so years to develop into an arts district with galleries, artist studios, interesting shops, condos, and restaurants. ‘First Friday’ is a monthly open studio and gallery openings celebration. Open Market, an open-air craft show, a flea market, and farmers’ market are held on Sundays.

For several decades, Fort Point Channel has been an artist community on the edge of the Seaport District of Boston. Pioneering artist living/working spaces have been maintained as a vital part of the neighborhood. Now the area is a destination for visitors taking in a plethora of cultural events.

Related terms to artwashing are pinkwashing and greenwashing. Pinkwashing is a term for when gays move into a derelict area and restore and revitalize the community’s housing and businesses. Eventually, these renovated properties are resold to gentrified heterosexual couples and families. The South End of Boston is an example of pinkwashing, as well as parts of the Roslindale and Dorchester neighborhoods.

Greenwashing is when corporations move into a marginalized community in order to develop buildings and facilities for its staff and offices that accent sustainable energy strategies. A strong public relations tool, this form of environmentalism sets the standard for future urban development and retrofitting.

For the anti-gentrification critics, urban deterioration should be left the way it is rather than reverse it through the introduction of art galleries, performance spaces, work/live lofts, and museums. Looked at reasonably, their ideologically-driven objection — that the introduction of the arts into a previously deteriorated neighborhood masks (even encourages) inequality — is total rubbish. The most dynamic parts of cities throughout the world are those that are diverse, culturally vibrant, and safe.

These anti-gentrification activists are rejecting a major piece of the urban fabric and clearly misunderstand the civic puzzle-solving process. This type of development must include strategically enforceable rules and regulations that a municipality can use to protect existing residents as well as small businesses. These strictures must give the existing community opportunities and options to upgrade, to become an active part of the regenerative process. Artwashing is about making a place vital and safer for everybody, not just for elites (the affluent). The reality is that this is progress, a way of moving forward that improves the quality of life for everyone.

This article previously appeared in The ArtsFuse and is republished by permission.