Tina Packer in Mother of the Maid

S&Co;. World Premiere by Emmy Winner Joan Anderson

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 08, 2015

Mother of the Maid

By Jane Anderson

Directed by Matthew Penn

Set, Patrick Brennan; Costumes, Govane Lohbauer; Lighting, James W. Bilnoski; Sound/ composer, Alexander Sovronsky; Fight choreography, Jason Asprey; Voice coach, Elizabeth Ingram; Stage manager, Laura Kathryne Gomez

Cast: Elizabeth Aspenlieder (Lady of the Court), Jason Asprey (Father Gilbert/ Scribe), Nigel Gore (Jacques Arc), Nathaniel Kent (Pierre Arc), Tina Packer (Isabelle Arc), Bridget Saracino (Saint Catherine), Anne Troup (Joan Arc)

Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre

Shakespeare & Company

Lenox, Mass.

July 30 to September 6, 2015

World Premiere

Through stage and film there have been numerous interpretations of the too brief, tragic and inspiring life of the peasant girl, Jeanne d'Arc (1412 – 30 May 1431). Mandated by God through visions the possessed teenager led an army with enough miraculous victories to liberate the Dauphin and see him crowned as Charles VII.

Having rallied the French army against British invaders she was captured and put on trial as a heretic. The Dauphin declined to pay ransom. Even though abandoned by God and the saints she refused to save herself by renouncing her visions. Just a girl of 19 she was burned at the stake.

There have been endless ways in which her story has been told. From a religious point of view it is the life of a saint. That occurred in the 20th century. She was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920.

A frequent point of view focuses on her bravery in battle and unwavering patriotism. Often there is a contrast between her sacrifice in defense of the Dauphin and his smarmy weakness. Ultimately, she was an expandable pawn in a game of politics that was beyond her comprehension.

For a better outcome the Maid should have prayed to Machiavelli rather than the virgin St. Catherine. Her blessed saint opted for having every bone in her body broken on the wheel rather than submit to rape by the emperor Maximian.

The emperor offered to marry her but Catherine countered with a vow of chastity as a bride of Christ. That resulted in a particularly brutal execution.

Saints can be so irrational.

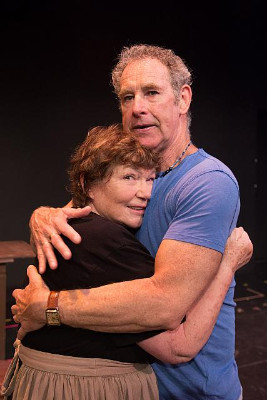

In a world premiere at Shakespeare & Company by Emmy winner, Jane Anderson, the story of Jeanne/ Joan, Mother of the Maid, is told from the point of view of her mother Isabelle. The play is a vehicle for the renowned Tina Packer supported by her touring partner from Women of Will, the redoubtable Nigel Gore as her peasant husband, Jacques. Other fine actors from the company include Tina’s son, Jason Asprey as Father Gilbert, and the versatile Elizabeth Aspenlieder as a Lady of the Court.

Early on in the first act, however, things fall apart. It is only mid to late in the second act that the production, unevenly written by Anderson and directed by Matthew Penn, gets on track. Eventually, in powerful and compelling scenes we have Tina being Tina with Nigel also off the leash.

Perhaps S&Co. might cut to the chase by eliminating the first act and including those stunning scenes as vignettes in a sequel of Gore and Packer’s Women of Will.

Initially, we are amused and engaged as a sprightly, sarcastic, ultra attractive and contemporary St. Catherine emerges from an awkwardly designed altar piece (Patrick Brennan). With a thin crown and flowing white gown (Govane Lohbauer) we are initially enchanted by Bridget Saracino. A newcomer to the company earlier in the season she was in the two-hander The How and the Why. There is every reason to want to see more of her.

Essentially, she serves to deconstruct the tale of The Maid. Among other messages she informs us that the play will dispense with any attempt to sound even vaguely French. Oh really!

How convenient and utterly wrong as the peasants Isabelle and Jacques speak with strong British accents. Wait a minute. Aren’t the Brits the enemy? Aren’t they the brutes who burned villages, raped women and slaughtered children?

The voice coach, Elizabeth Ingram, has developed ersatz British accents for Aspenlieder and Anne Troup as Joan. I don’t know what to make of the accents of Asprey and Nathaniel Kent as Joan’s brother Pierre. Add to this mulligan stew of cockamamie British/ French dialect the unabashedly American delivery of Saracino.

Consider that Jeanne d’Arc has morphed into the surname of Arc. What we have is the Arc family from the village of Domrémy-la-Pucelle. Set in the early 15th century the play occurs during the International Gothic era. France was emerging into the Renaissance at a slower pace than Italy. So Jeanne is a character of the late medieval period. That perhaps explains her blind faith, religious and political visions, and self absorbed fanaticism.

Yeoman names like Smith, Cooper, Sawyer and Wainwright where just evolving in England. For Jeanne the d’Arc means that she is from Arc which is a region. It is like the name of the Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Which is to say that he came from Caravaggio. Today he is commonly referred to as simply Caravaggio.

Following the lead of the naughty and playful St. Catherine this play by Anderson follows the trope of conveniently reconfiguring Joan as a proto feminist. She is a strong willed teenager who defies her parents, dresses like a man, goes off to fight in a war, cuts her hair, binds her breasts, and refuses to marry a nice boy from the village.

All of that makes her a modern woman which, given the time frame, certainly she was not. From a contemporary vantage point she is better understood as a delusional hysteric, religious fanatic, and clinical psychotic. Today a young woman cavorting about talking about divine visions would be treated and medicated. Nobody would declare her a saint even if she racked up three confirmed miracles.

Enduring the first act, where Packer often faltered over lines and motivation, we thought perhaps that we were seeing a play in the tradition of Pirandello. Frankly, that would have been more interesting and enjoyable as broadly suggested by the St. Catherine character.

A romping send up could have been fun. Instead, the first act teetered along between coy deconstruction and playing it straight. The performance of Troup didn’t help in sorting this out. We would have benefited from a better and deeper understanding of her motivation. But this play is more about the responses of Isabelle, the undying love of a conflicted and grieving mother, than insights into the many conundrums of Joan.

From simple, overwrought peasant girl on a mission from God, we next encounter her suited up as a warrior woman (a familiar theme in Packer’s anthology Women of Will). She became a celebrity in the court of the Dauphin. When Isabelle makes a 200 mile trek to see her daughter she is kept waiting for hours. Joan is too busy hanging out with Charlie (they are on a first name basis).

Another miscalculation is the handling of Joan’s brother Pierre. Isabelle insists that he accompany and protect Joan. Jacques states that he can’t be spared. Father Gilbert, a straw in the wind, suggests that the Church will pay to replace his labor. He first endorses and later abandons Joan.

When all goes south Jacques ridicules Father Gilbert and his mantra of "God's will." One may feel and express that today but in the 15th century his outburst would risk arrest or worse. There are too many such anachronism that undermine the veracity of this wide of the mark account of history. It seems that Anderson has not done much fact checking. Much of her writing is a literary fabrication of actual events.

Which is OK if it works as compelling theatre. Mostly, however, the play is underwhelming.

The peasant Pierre is knighted, given a horse and armor, and lives well at court riding on Joan’s reputation. None of that is particularly convincing. Jacques angrily wants to know where his son was when Joan got nicked by an arrow. During that confrontation the son pulls a sword on his father. Pierre offers a bit of red herring about that signifying incident. He has saved the arrow head as a souvenir.

Fast forward to the second act and raison d’etre (that's French by the way) for the play. The scene between mother and daughter in prison provides vintage Packer. She tears our hearts out tenderly washing and dressing her daughter in a loose gown. Joan, after months in prison, is alone, scared, sick, abandoned and utterly wretched. Here Troup is superb as the condemned girl, barely 19, who just wants her mother.

The final scene, with Gore displaying massive chops, sees him witness the barbaric execution of Joan. Reduced to ashes onlookers rush to scoop up charred bones as souvenirs. As an act of charity a soldier gives him a rag with fragments of her remains. The rest of her incinerated body is gathered up and tossed in the river.

Strong stuff! Surely Packer deserved her standing O during the curtain call.