A Last-Minute Visit with Joseph Cornell

Imaginative Attachments

By: Shawn Hill - Aug 05, 2007

Joseph Cornell: Navigating the ImaginationPeabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.,

Co-organized with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., as part of "American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius," by the NEA.

April 28—August 19, 2007

Upon entering the Joseph Cornell show at the Peabody Essex Museum (his first major retrospective in 26 years) one is reminded that, due to the fragile nature of many of the works, lighting is kept quite low. Don't be put off by this limitation; give your eyes time to adjust, and Cornell's idiosyncratic but crystalline and orderly worlds will emerge from the shadows, revealing a wealth of secrets.

While long familiar with Cornell's boxes, I had no idea of other media he worked in. This comprehensive show, a series of rooms nestled into the Peabody's asymmetrical, multi-layered space, provides thematic glimpses at experimental films, potentially interactive scrapbooks and folders, paintings and flat collages, and, in every room, in large glass cases, the boxes.

Especially surprising was the artist's late career focus on pin-up girls and female nudes. The colorfully plumed birds in the cages of grids and items arranged in loose geometries are more often reproduced, but ample evidence in the show points to Cornell's fascination with ballerinas, movie stars, historical queens and goddesses out of myth.

Cornell drew on a variety of influences, including Surrealism and cubism, but also reacted to the Abstract Expressionism popular in his most productive era (he too splattered and dripped when called for, inside his glass-fronted boxes) and anticipated the postmodern practice of appropriation by several decades. All of his imagery is repurposed from other sources; a true collagist, he doesn't draw, he cuts out, paints over and rearranges, and occasionally traces and carves.

There's a wily sense of humor in the show, a flashback to the mix of pop culture and high art that was at a sensitive artist's fingertips over a half century ago. Cornell worked in series, including his "Soap Bubble Sets" (each featuring some variation of a bubble blowing pipe, recast in plaster, and all sorts of game-like arrangements of wine glasses, marbles, glass balls, hoops on rods, corks on hooks, and other items that suggest a forever arrested sense of movement) and his Medici children "Slot Machines."

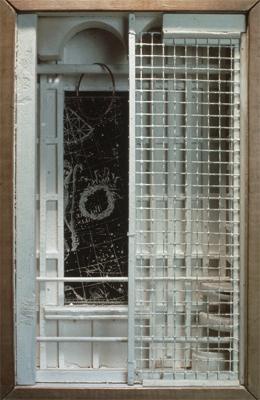

There are three from the latter series in the show, and they evince Cornell's most serious themes. In the central panels, Renaissance era children, now in faded reproductions, stare out from behind glass that has been lined in minimal black geometry. Rather like grisaille stained glass windows if designed by Mondrian. Flanking these large central portraits are shelves filled with blocks (in the "Medici Princess," some of her blocks have tumbled to disarray). Not literal slot machines, these evoke the frontal display of those gambling devices, referring to the changing tides of fate, the streams of chance that make some children royalty while others know only poverty and obscurity.

Quite similar in design, but very different in execution, is Cornell's homage to screen siren Lauren Bacall. The "Lauren Bacall Penny Arcade" is an elegant art deco altar dating from the period of the actress's earliest fame. Her enigmatic, smoky-eyed beauty, captured in one of a multitude of press photos from her initial media blitz, is framed in a central glass window by smaller shots from her childhood on either side. Apertures to admit a red ball and play some sort of game are on both the upper and lower right of the frame. In the row of images above Bacall's face (befitting the life of a native New Yorker), we see a row of skyscrapers, a mini-landscape of Manhattan. Somehow the sleek lines and sparkling windows of the buildings relate to the physical perfection of the young model and actress discovered on those same streets.

References to alchemy and science abound in the show, but the real revelation is simply Cornell the handmade creator and designer. In his own workshop, he moved from using found boxes and frames to building his own, and the show lets us see a selection of his actual materials and the tools he gathered as he perfected his carpentry skills. The impulse to combine, to collect, to re-order for personal exploration may be his legacy to the arts.

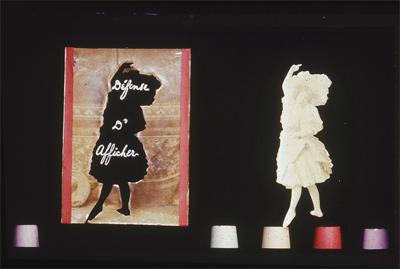

One of the most powerful images of the show is one of the smallest: "Post No Bills: Object (Défense d'Afficher)" (1939). This work is deceptively simple. From an old-fashioned carte-de-visite advertising a dancer, he has cut out the performer, leaving a void in silhouette. The dancer has flitted from precarious balance over a row of thimble-sized stands, in various colors. These perches run off to the right at measured, musical intervals. In the silhouette, still flanked by the brocade curtains and stage setting of her backdrop, he has painted the legend "Défense d'Afficher." Rather than being prohibited from making attachments, Cornell's work is a testament to the impulse to create and connect by whatever means are needed.

Joseph Cornell travels to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Oct. 6, 2007—Jan. 6, 2008). The exhibition is accompanied by a 48-page publication focusing on the artist's singular way of seeing (April 2007). It includes an essay by curator Lynda Roscoe Hartigan. A second publication, a fully illustrated book written by Hartigan, will be published by Yale University Press later in 2007.