The KUMU Art Museum

Tallinn, Estonia

By: Zeren Earls - Aug 01, 2015

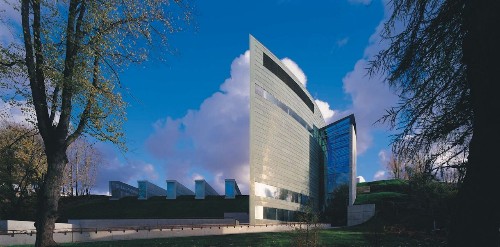

Soon after its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the Republic of Estonia revived its long-time dream of having a new museum for Estonian art, which had been interrupted due to the beginning of World War II. In 1993-1994 an international competition was organized, to which architects from ten countries, including the USA, submitted designs. The winning design, by a young Finnish architect, Pekka Vapaavuori, became a reality in 2005. Another competition was held to name the museum, resulting in the name KUMU — a shortened version of the Estonian word kunstimuuseum (art museum). The new museum opened its doors to the public in February of 2006.

Winner of the European Museum of the Year Award in 2008, the KUMU Art Museum is a most impressive exhibition venue in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital city. Located at the edge of Kadriorg Park, which houses Kadriorg Palace, constructed by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia in 1718 and now operating as the Kadriorg Art Museum, the KUMU soars as the new youthful face of Estonia, as opposed to the baroque splendor of the palace, where large collections of Russian and Western European art from the 16th to the 20th centuries are displayed.

The state-of-the-art KUMU has seven stories, two of which are underground and house most of the collection of 58,000 works of Estonian art. The permanent exhibition halls cover Estonian art and sculpture from the 18th century to the 1990s; including the Soviet era. The temporary exhibition galleries display both local and international art, from classical works to contemporary. The façade of the building serves as a large screen for video art.

The permanent exhibition hall on the third floor is called the “Treasury.” This section displays early classics, from the 18th century until the end of the Second World War. The fourth floor exhibition space is dedicated to Estonian art from the second half of the 20th century (1945-1991) and is called “Difficult Choices.” The fifth floor is a temporary exhibition space dedicated to contemporary art.

Beginning my tour in the “Treasury,” I first viewed Baltic-German paintings by Estonian artists who either are ethnically German or have attended academies in Germany. In this category, the 19th-century paintings “Girl Feeding Chicken” by Karl Timoleon von Neff, “On the way Home” by Lorenz Heinrick Petersen, “Moment of Rest” by Theodor Albert Sprengel, and “The Faithful Guardian” by Johann Köler are outstanding examples of the reality-based genre as masterful paintings of Estonian life. Also by Köler is a wonderful mythic painting, “Monks Chasing Lorelei,” which depicts the long-haired German water spirit running away from cross-wielding monks as her lyre floats in the waves.

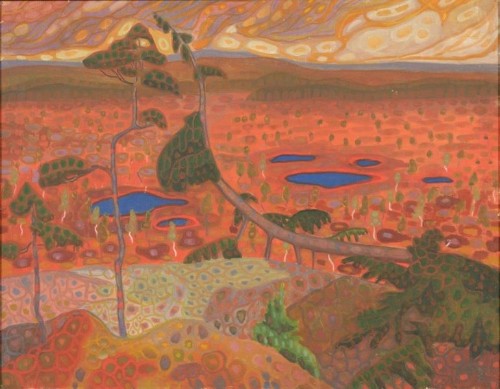

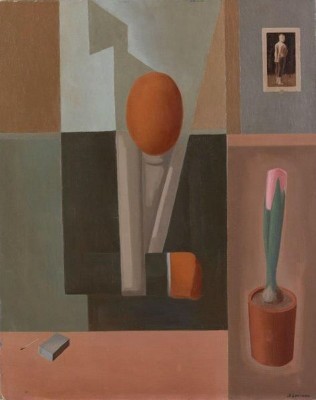

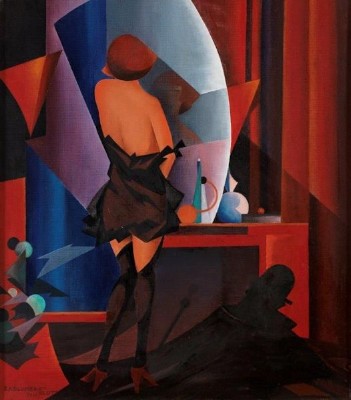

The “Treasury” also includes works in the category of “classical modernism,” which highlighted individual creativity, embracing a diversity of styles in the first half of the 20th-century. In “Norwegian Landscape with Pine” and “Meditation (Landscape Lady),” painter Konrad Mägi applies his own state of mind to elements of nature through a vigorous and distinctive use of color. “Illness” by Mart Laarman depicts a faceless, mannequin-like patient freed from a human context, addressing a universal idea of humanity. Eduard Ole’s “Table” is a canvas of geometric abstraction with repeated circles in pure shades of color, including the clouds that appear through the window. Other paintings of note in this section are “Swan Hunt” by August Jensen, “Street in Tallinn” by Peet Aren, “Sunday” by Felix Randel, and “Toilette” by Edmond Arnold Blumenfeldt.

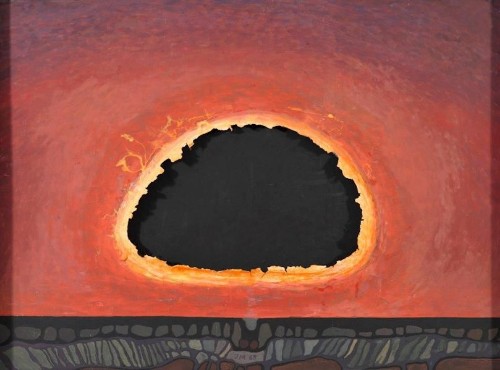

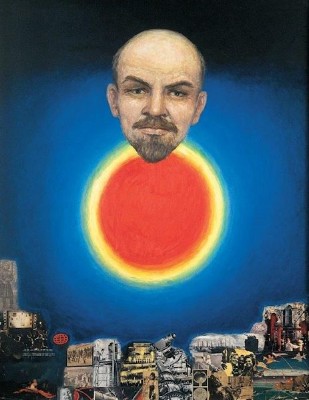

"Difficult Choices” on the fourth floor is a historic collection of work from the Soviet era, beginning in 1945, when subjective art was suppressed in favor of collective expression. The galleries reflect the attitude of the Soviet state towards art, which took the form of post-war socialist realism, glorifying state leaders, workers, soldiers, and farmers, all working for the collective good. However, there was an art revolution in the 1960s, when artists abandoned the official Soviet art canons, revealing new ideas and strategies for the art of the time. Two works, painted a year apart by Ilmar Malin, exemplify this break, as well as the artist’s dilemma. “Setting Sun,” also called “Dying Sun,” is a depiction of a black sun made out of adhesive paper against a tempera background on fiberboard. The same artist’s oil on canvas, “Lenin,” shows the head of the leader above a bright sun in the sky, rising over the industrial city below.

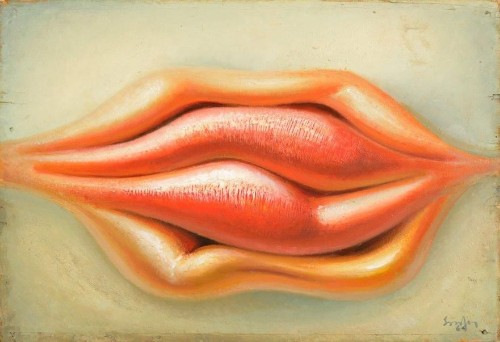

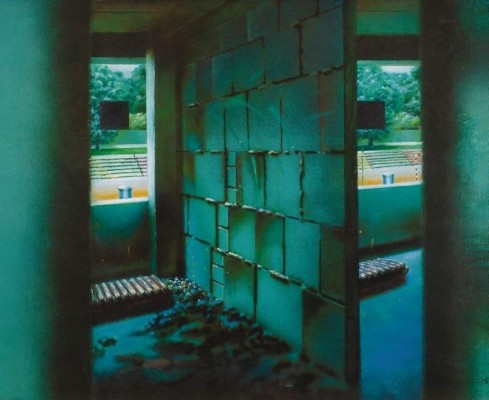

“Feel at Home,” a temporary work by Marko Mäetamm, shows a man and a woman with paper bags over their heads sitting on a couch, underlying the hard dilemmas they face in life. Among the works that shifted the boundary between what was permitted and what was prohibited in the art of the period, offering a broader range of art that could be considered realist, are “Game” by Toomas Vint, “Two Thoughts” by Kaijo Pöllu, “Lips” by Ulo Sooster, “On the Leningrad Highway” by Rein Tammik, and “Evening” by Ando Keskküla.

Many of the artists pursuing new ways of expressing themselves went underground during the Soviet era; these works were acquired by the Art Museum of Estonia after independence and are now in the KUMU collection of Estonian art. A new exhibition was being set up in the gallery for contemporary art on the fifth floor during my visit. Therefore, I was unable to see any of the current work. Nonetheless, I would highly recommend a visit to the KUMU in the beautiful city of Tallinn.