Wendy Whelan Duet at Jacob's Pillow

Some of a Thousand Words with Brian Brooks

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 29, 2016

Some of a Thousand Words

Choreography by Brian Brooks

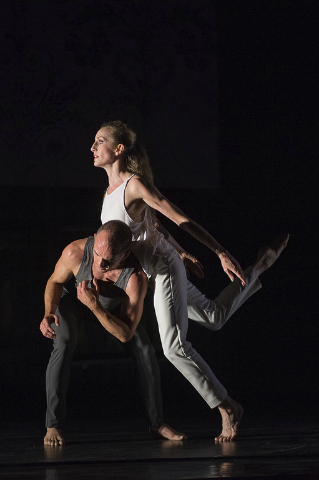

Performers, Wendy Whelan and Brian Brooks

Musicians, Brooklyn Rider: Nicholas Cords, viola; Johnny Gandelsman, violin; Colin Jacobsen, violin and Michael Nicholas, cello

Music: Philip Glass, String Quarter #3 Mishima; Jacob Cooper, Arches; John Luther Adams, The Wind in High Places; Colin Jacobsen, BTT, Tyondai Braxton, ArpRec1

Lighting Design, Joe Lavasseur; Costumes, Karen Young

Jacobs Pillow Dance|

Ted Shawn Theatre

July 27 to 31, 2016

After 30 years with the New York City Ballet, principal dancer Wendy Whelan, having mastered a repertoire of 50 dances many of which she originated, retired in 2014.

Now 49, which is near the end of the career of most ballerinas, she has embarked on a quest for self discovery working with several choreographers who are creating dances tailored to her strengths and style.

In 2013, with a world premiere of Restless Creature at Jacob’s Pillow she performed duets with four choreographers Kyle Abraham, Joshua Beamish, Brian Brooks, and Alejandro Cerrudo.

Expanding on their initial collaboration First Fall with Brian Brooks they have returned to Pillow with a single work that includes and extends from that Some of a Thousand Words. With a performance by Brooklyn Ryder it comprises several sections, solos by both dancers, duets and a passage featuring the musicians.

With its departure from the vocabulary of classical ballet, even more so than in 2013, it is usual to identify this work as defined by Post Modernism. That’s an umbrella term for the departure from the modern movement and style that dominated the arts from Impressionism through all of the isms that exploded into Pluralism and Globalism by the late 1960s.

But for the dance we saw last night, with its roots in the neo classicism of George Balanchine, this transition with its linearity and artifice is a dance to be appreciated by aficionados embodying ars gratia artis. It is identified as a form of Mannerism.

It is an extension of the classical and not a Post Modern break from and rejection of it.

Mannerism is a phenomenon that can occur at any time and represents a niche and transition, a struggle and aesthetic crisis, a blip between more grounded and sustainable movements. Perhaps the first such instance was the brief Amarna period of New Kingdom Egyptian art under the heretic pharaoh Ankhenaten. His magnificent city was destroyed in early Dynasty 19 when Egyptian art rejected this remarkable experiment and returned to a conservative style. After the death of the boy king Tutankhamum, significantly, after what may have been a coup Egypt went back to basics under the general Horemheb. The rare and exsquiste art inspired by a philosopher king was crushed by militarism.

Whelan encountered the master Balanchine during her debut with the company and his death in 1983. But his transition of the classical Russian vocabulary modified into neo classical modernism was rooted in the company shaping her development and style.

The vision quest which is magnificently expanded in this remarkable work with Brooks is an extension of and evolution from traditional and modernist ballet. It represents a break from expectations and restraints to find a dance that is unique, personal, expressive and experimental.

It is well known that she has struggled with physical adversity both early on and more recently from hip surgery after an accident. The dance, with its languid pace and legato extensions of arms and body, is more like a Tai Chi of meditative spiritual introspection than the sanguine energy of a top-tier ballerina.

Magnificently, with a stunning experience for the audience, Whelan is presenting the late style of an artist enduring physical limitations but presenting the compelling subtlety and emotions of hard-earned life experience.

It reminds me of John Cage who liked to state that “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.”

Here dance is reduced to its essence accompanied by challenging and exquisitely performed music.

That notion of Mannerism was triggered by a banner suspended above the length of the stage. The set design is not credited in the program. The patterning might evoke wall paper to some or an element of the Baroque. It is, however, an signifier of the grotesque which was unique to the artifice of Mannerism.

It derives from the term maniera which roughly translates as style and defined the cusp between the late High Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque. It was a brief outburt of playfulness, invention, games and deceptions. As an art form it is always distinct to recognize and impossible to define. There is an element of deliberate obfuscation or what Susan Sontag has discussed as against interpretation. Accordingly, it would be unproductive to explain what Some of a Thousand Words means. Take a clue from the title that there are millennial possibilities in approaching this dance.

Audiences like to know and understand what they are looking at. Other than the compelling grace and majesty of Whelan this may have been a difficult experience for many viewers. It entailed a surrender of expectations and acceptance of the generosity that was being presented.

During the High Renaissance artists in Rome broke into and explored the underground “grottos” of the ruins of the Domus Aurea or gilded palace of Nero near the coliseum. There by torch light they studied, sketched and created inventions on the decorative wall paintings. Hence these designs are identfied as 'grotesque.'

This was particularly energizing to the School of Raphael and his primary adjunct Giulio Romano. His “temporary” pavilion the Palazzo del Te in Mantua displays all of the variations of Mannerism including a room of Roman inspired grotesque designs.

Exactly like that banner above the stage at Pillow.

Most people will recognize Mannerism from the elongated, ethereal figures painted by El Greco.

That is precisely what I felt in the nubile torsion, the echoing of movement triggering movement, plastic extensions, liquidity of Whelan and her partner Brooks.

The suite began with Whelan lying on the floor as cellist Michael Nicolas provided an ostinato Arches by Jacob Cooper responding to a background track of hypnotic minimalism. The pace was slow and solemn.

With measured intensity Whelan as dancer and character awakened to the music and gradually stood and began to explore inventions with the music. One might think of Nijinsky in that opening segment of L'après-midi d'un faune.

Creating a sense of closure there was a mirror image as the dance ended to music of Philip Glass with the dancers fallen to the ground, arguably expired.

The metaphor of falling and extensions in precarious balance pervade the piece. There was a lot of shifting off line into vectors. This was conveyed in the many variations of leaning and falling. It also uderscored dependence and absolute trust between the partners with palpable potential for risk and possible damage.

With wonderful invention and many variations during the duets they worked with generic chairs. There were variations from standing to sliding down, falling off, and laying extended horizontally.

More than partnering in the manner of classical ballet they were collaborators, improvisers and inventors. There were brief passages where they executed lifts but mostly they appeared as separate but equal. There was similarity but not replication in their movements. It was subtle but they were doing slightly different things when it would be the norm to expect unison.

There were graceful transitions. Several times this entailed them walking in ever widening circles. Either they both left and then appeared to a new passage of music, or one remained for a solo. There was also a time when they both left and the quartet was featured.

In addition to being a chorographer, which preceded his career as a dancer, Brooks is also an athlete and runner. It has been discussed that hitting the wall, the stamina and adversity of a marathon is a part of what he conveys.

This was seen during a stunning sequence in which Whelan is pushing against his bent over form. He provides the physical resistance as with legs dug in she forces their movement toward a strong parallel light (designed by Joe Levassaur). It is the surrogate of struggling against a powerful head wind.

Overall, this evening, remarkably, felt more advanced and resolute than what we experienced in 2013. There was the sense that both had gone much deeper in finding a new plateau for their collaboration.

In program notes it was discussed that Whelan loves to be in the studio and much of the work, different than working with a company, entails improvisation. This is different from the norm in which a choreographer develops a dance which is then set onto the dancers. In this instance Whelan is involved in every phase of the development. The choreography is created in sync with her body, its limitations and assets.

As artists age there is a process of letting go as well as adaptation of more limited but richer possibilities. Often there is a struggle to cope with physical ailments, pain and suffering. It can be magnificent and inspiring when this become embedded in the work.

Like Mannerism this new work is a developent of art that stands aside from the mainstream of contemporary dance. It would be unlikely to see it performed by anyone other than Whelan and Brooks.

It is important to note that she is working alone with partners. Whelan has not formed a company. There is no baton to pass to the next generation.

It is fair to speculate, however, that many younger dancers are looking long and hard at this seminal work and what it might mean for their own practice.

Truly we feel honored and blessed to have these two life changing encounters with a national treasure of dance at Jacob’s Pillow. May her tribe increase.