Frank Lloyd Wright's Stuff

Architect Was Less Or More Than He Boasted

By: Mark Favermann - Jul 28, 2008

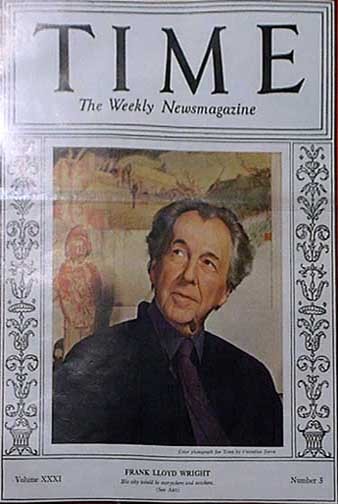

After being quite low in terms of major projects, recognition and family as well as suffering severe financial problems that resulted in the loss of his beloved Taliesin in a bankruptcy, Frank Lloyd Wright needed to have something positive happen. It did. After much work and a bit of luck, in 1937, Frank Lloyd Wright's career was resurrected. He was around 68 or 69 years old, maybe older as he lied about his age. This should give all late bloomers hope.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a wonderful self-promoter. He was a very persuasive and gifted orator, and he very much enjoyed giving public lectures. Part of Wright's self-promotion may have been a little exaggerated, even fabricated or just plain mythmaking. He felt that these added to his luster as a great architect and a great man.

Wright designed his buildings as total projects: the details, the furnishings and the artwork as well as the over all structure and plans were extremely important to him. In other words, he was an ultimate control freak. A client of his had to buy into the Wrightway or it was presumably the highway for them. Before Kool-Aid, Wright forced his clients to drink his architectural brew. This total control suggested that Frank Lloyd Wright created every aspect of his projects himself.

Myth #1: Frank Lloyd Wright designed everything in his buildings entirely alone.

Fact: He was the master designer of each of his projects. FLW never gave much credit to anyone else, however, he had talented collaborators on everyone of his projects. This was everyone from his often gifted apprentices at Taliesin to innovative engineers to craftsman fabricators to extremely open and flexible clients. Most of his projects ran over budget, so his clients had to be flexible as well as often generous.

Several years ago there was a wonderful exhibit at the National Heritage Museum in Lexington, Massachusetts on a rarely acknowledged Frank Lloyd Wright collaborator, George Mann Niedecken. The exhibition was "Designing in Wright Style:

Furniture and Interiors by Frank Lloyd Wright and George Mann Niedecken." There were at least nine residences that the two artists collaborated on. And Wright was influenced by the more sophisticated and better traveled Niedecken who was primarily an interior designer but who also crafted exquisite furniture and fittings.

Therefore, Wright's integrated designs for home furnishings were not the product of his vision alone. From around the turn of the century through World War I, he collaborated with Niedecken. Their design collaborations took place between the years 1904 to 1918. These years were Wright's Prairie Style period. Along with other projects, they worked on the famed Robie House together in Chicago between 1907-1910. Both men were committed to simplicity, honest materials and decoration derived from nature.

Niedecken had been working intermittently in Wright's studio for several years by 1904 when he painted the landscape mural encircling the dining room of the famous Dana House in Springfield, Illinois. Several key objects in the 1999 museum exhibit demonstrated this strong collaboration. These included a copy of The House Beautiful, a book illustrated by Wright and hand-printed in 1896-87 in a limited edition of ninety; a Wright barrel chair, ca. 1900; a remarkable combination library table-desk-bookcase-couch of Niedecken's design, made for the Irving residence in 1911; and a Bogk carpet that Wright designed and Niedecken had manufactured in 1917--a great rarity because very few of Wright's Prairie-style rug schemes were ever realized.

Myth #2: Another mythic influence of Frank Lloyd Wright was he was given a set of blocks that were developed by Friedrich Froebel in the 1830s. So as one version of the story goes, FLW was interested in architecture at an extremely early age. The other version was that his mother wanted him to be an architect. Supposedly, she had dreamed that he would create great buildings. These geometric maple blocks that could be assembled in a multitude of ways allowed Wright to learn geometric form, mathematics and creative design. Supposedly, his mother purchased the blocks at the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia at a presentation of Froebel's theories about kindergarten. As the legend goes, FLW's whole career was influenced by his playing with these geometric Froebel blocks as a small child.

Perhaps, Wright's mother did introduce him to Friedrich Froebel's ideas and to Froebelian toys. The blocks encouraged the child's sense of three-dimensional composition and paper to fold in various shapes, aiding the child's perception of planar elements. She was supposedly progressive-minded. According to Wright, he conceived of buildings in his imagination, not first on paper, but in his mind, thoroughly, before touching paper. Wright designed in his head while playing with Froebel blocks.

Personally, I don't buy the Froebel Blocks story.

In his later life, Wright never failed to credit Froebel for his earliest architectural yearnings. One of Wright's later gifted architectural partners was Edgar Tafel, who had as a child attended the Modern School, a school based on Froebelian principles as well. Here myth and reality may have coincided: just perhaps, Tafel's mother was the progressive-minded mother and FLW liked the idea of it.

One problem that I have with the story is that most architects in the 19th century generally came from wealthy families. The Wright family was middle class but certainly not affluent. Would FLW's mother have wanted him to take up a profession that was poorly paid? His father was a ne'er-do-well minister. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright went to the University of Wisconsin at Madison for several semesters and studied civil engineering courses. There was no architectural program there.

Perhaps, back in the late 19th Century, a combination of engineering courses and architectural apprenticeship was the norm, but also maybe as many callow youths still do, Wright wasn't sure what he wanted to be preadolescent —blocks or no blocks. More likely, Wright found his true calling in his years as a draftsman in Louis Sullivan's Chicago architectural office. So, maybe this story is "a should have been," an apocryphal myth rather than a real influential early life experience? The story is nice, but not really necessary to the greatness of Wright.

Myth #3: After procrastinating for many months over the design of a week-end home, when wealthy Pittsburgh department store owners Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann called Wright to tell him that they were on their way to see the plans for Fallingwater, Wright drew up the full set of drawings in about two hours and presented them to the clients as a finished plan package. Supposedly, Wright had the complete concept in his head and rapidly set it down on paper. I doubt if this is what really happened.

This would be like Ludwig von Beethoven writing his Symphony No. 9 in D minor in a couple of hours without any revisions or Michelangelo carving David in an extended afternoon without any wrong chisel marks. It couldn't be done. What probably happened was that Wright and his apprentices had done a number of preliminary sketches in rough and more refined forms. When the Kaufmanns called to say that they were on the way, Wright had everyone stop what they were doing and finish the drawings as completely as possible. The project became arguably the greatest house design of the 20th century —with the actual plans created incredibly speedily or not. It really does not matter.

Perhaps, Wright did come up with a few creative wrinkles during the rushed drawing phase. That often happens throughout the creative process. An apprentice or two already enamored with the great master, Frank Lloyd Wright, verified the master's story of putting ideas to paper in a super rapid manner. Thus, the myth was born: like Athena from the forehead of Zeus, Fallingwater sprang from the head of Frank Lloyd Wright. I guess that it is sort what happened, even if it wasn't exactly as advertised by Wright and his loyal acolytes.

On a recent trip in June, I visited Fallingwater. It is magnificent. Though a bit smaller than what one expects, it is architectural greatness. Wright got it quite right. As the Kaufmanns were sophisticated clients, they gave spark to the creative process as well. By the 1930s, his professional if not chronological contemporaries, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had taken Modern Architecture or the International Style (as termed by the then the Museum of Modern Art's architectural and design curator and later architect, Philip Johnson) beyond what Wright had done earlier in the 20th Century. They had created a sparer geometry of form and space.

With Fallingwater, Wright had achieved an architectural statement on an unparalleled level. There was a human warmth and connection to nature with his design beyond pure abstract design elegance. This project was the one that got Wright back to the top of the architectural pyramid. How he got there is interesting as well.

The way back to prominence was started in 1928 when he was around 61 years old. His third wife Olgivanna who was 30 years his junior aggressively assisted him in marketing and selling himself. He published an Autobiography in 1932. Establishing the Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin and later in Arizona also in 1932, Wright had an income base from apprentices and a vehicle to espouse his theories on architecture, urbanism and nature. Wright taught and the apprentices paid; they learned from and worked for the master. Wright made speeches at this time that were both provocative and entertaining. His lectures spread the Wright word. In his public speaking, he created the boastful all-knowing Frank Lloyd Wright character that seemed to be the one we are left with.

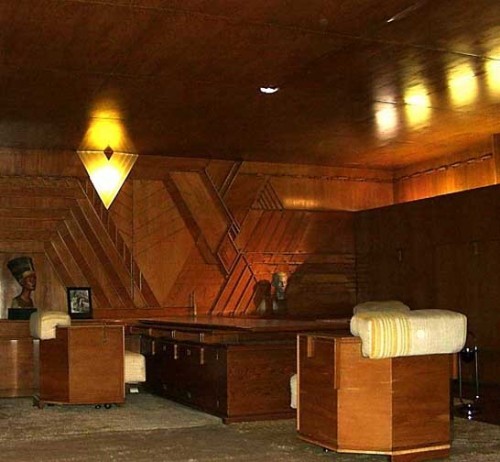

One of the apprentices who was captivated by Wright's 1932 autobiography was a young art and design connoisseur by the name of Edgar Kaufmann jr. He was not into the manual labor required of the other apprentices. But, young Kaufmann had a good car that he could pickup potential clients in and take them to see Frank Lloyd Wright, and more importantly, he was able to introduce Frank Lloyd Wright to his wealthy parents in 1934. The first project that Wright did for the Kaufmanns was to redesign the offices at Kaufmann's Department Store in Downtown Pittsburgh in 1935. This elegant distinctive mostly wood interior is now part of the permanent exhibits at London's Victoria & Albert Museum.

Wright worked on many potential projects for the Kaufmanns, but only the office interior, Fallingwater (1937) and the Fallingwater guesthouse (1939) were ever built. But they were enough to resurrect the career of the architect. The rest as they say is history. The majority of Frank Lloyd Wright's approximately 350 building commissions came after this time.

It has been said that Fallingwater is the perfect marriage of building structure to site. Built boldly over a waterfall, there are layered ledges that reflect the layers of sandstone at the site. The interiors open to the natural setting. These spaces are somewhat small while somehow evoking spaciousness. There is a magical quality to the spaces in and around the house. Several apprentices were involved in the project including Byron (Bob) Mosher, Edgar Tafel and Wesley Peters. Civil engineer Mendel Glickman supervised the engineering for Wright.

Unlike many of Wright's clients, the Kaufmanns challenged Wright during the design process and were able to add and subtract elements of the original Wright design. Wright tended to dictate to not collaborate with his clients. I feel that this collaboration led to the greatness of the result.

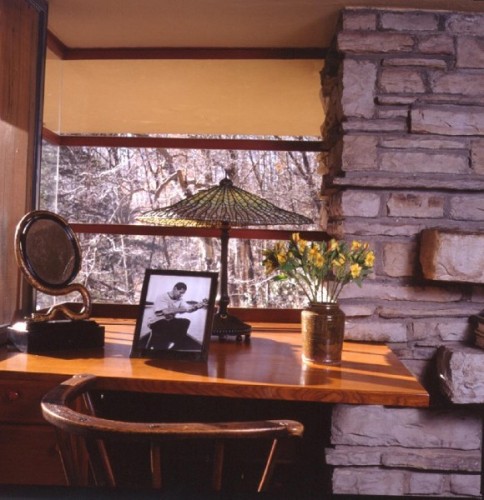

Fallingwater's interior spaces are reflective of this collaboration. There are Wright's absence of surface elements, the natural color pallet, indirect lighting spacious open rooms, defined activity areas and fine craftsmanship. The Kaufmanns gave the house a lived-in warmth insisting at times upon their own choices of furniture by contemporary designers and rustic three legged more stable chair choices, modern bathroom conveniences and an abundance of storage and shelf space.

Pillows and throw colors and fabric were chosen by Mrs. Kaufmann. Integrated bookshelves were a Kaufmann detail as well that added color and ornamentation. Built-in seating and polished stone floors tie the living room together with the fireplace which is an asymmetrical focal point. Often Wright would set furniture structurally in the floor so the client could not move it around. Wright just knew better than his clients where things should be placed. This was done in some instances at Fallingwater.

The natural color scheme is set off by Wright's favorite Cherokee Red color applied to windows and various details including a large kettle used for brewing hot drinks. There is a modest looking dining area that allows for flexibility and expansion to accommodate larger parties. The inside/outside aspect of the house underscores Wright's involvement with his nature ethos and the Kaufmann's early concept of conservation and personal involvement with the natural environment.

The house is a home of all seasons. Fallingwater reflects and frames views of the natural environment in spectacular ways during every season. Vistas and balconies allow the house to be greatly enlarged. Rooms have an inside and an outside feeling. This is underscored as bedrooms double in size with the addition of the outside terraces. Windows open the space to the natural setting while being set to allow maximum viewing due to the fenestration. Much social activity was celebrated on the exterior elements of the house. It was a true party house that was used as a retreat for family, friends and employees.

After a career as an assist curator of design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a long teaching career at Columbia University, in 1963, Edgar Kaufmann jr. donated Fallingwater and its over 1500 acres to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. He also gave an endowment to assist with its upkeep. Edgar jr. donated 900 pieces of art and craft objects from his extensive collection as well. In recent years, the house required extensive structural support work, window replacement and concrete surface repairs. Wright's own indifference to standard engineering and just age caused the damage. These repairs and refinements have all been achieved with great elegance.

Fallingwater underscores Frank Lloyd Wright's greatness. In the early 1990's, the American Institute of Architects designated Frank Lloyd Wright as the greatest American architect. Hyperbole and myth are not really necessary to embellish this architectural genius.