St. Petersburg

The Cultural Capital of Russia

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 26, 2015

As we traveled further east from Tallinn to St. Petersburg, approaching the Russian border, the character of our surroundings changed. A high wire fence flanking a bridge over the river that creates a natural border between the two countries kept cars and people out of harm’s way. Vita reminded us to put our cameras away, as no pictures were allowed at border control. An officer came to the bus to collect our passports and handed out two forms to be filled out — one for entry and one for exit at the time of our departure. As soon as we cleared a gate crowned by large cut-out metal letters that spelled “Russia” in Cyrillic, the beautiful city began unrolling before us.

The Domina Prestige Hotel, our home for three nights, was right on the Moika River embankment. Following a brief orientation walk, Vita suggested we go for a boat ride on the river. Enthusiastically receiving her suggestion, we rode through the canals for about an hour, passing under bridges with iron filigree railings guarded by statues at the end. Magnificent palaces and buildings with ornate facades, each designed by a famous architect lined the water’s edge. Boat docks teemed with people, signaling that this was the second largest city in the country, with a population of 5 million.

Peter the Great, inspired by the canals in Amsterdam and Venice, founded St. Petersburg at the mouth of the River Neva in 1703 and called it the country’s new western capital, built on 42 islands and connected by 500 canals. The tsars and tsarinas of the empire lived the high life in St. Petersburg in opulent palaces, inspiring art and architecture throughout the city, until 1917, when Lenin moved the capital back to Moscow following the Bolshevik revolution. However, St. Petersburg remained the cultural capital of Russia, with its many museums and theaters.

One optional cultural highlight on our first evening was a Russian folk show called “Feel Russian” at the Nikolaevsky Palace. Upon entering the 18th-century palace and before going up a marble stairway, we were greeted by a trio in period costume — two women in crinoline and a gentleman in a wig — as a classical quartet played in the background. Welcomed as the “guests of the Grand Duke,” we then moved up to the performance hall. The folk show itself featured the “Peter’s Quartet,” singers specializing in folk songs and Russian Orthodox hymns; “Maidan,” a Cossack song-and-dance group; and the “Stars of St. Petersburg,” a dance troupe performing acrobatic feats. The groups were accompanied by a folk orchestra featuring the balalaika. The performers were all highly skilled and received much applause for their virtuosity. During the intermission we were treated to complimentary champagne, vodka, and wine, along with red caviar canapés.

In the morning we started out on a city tour. As we walked along one of the canals, a dazzling ornate church with five onion domes shone in the distance. I reached for my camera instinctively and later found out that the building was the Church of the Savior of Spilled Blood, one of the main Russian Orthodox Cathedrals, built in 1883 on the spot where Emperor Alexander had been assassinated in 1881. The church, with its brightly colored onion domes and glittering spirals, modeled after Moscow’s St. Basil, had been ransacked during the Bolshevik revolution and used as a depot during Soviet time. Under the auspices of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, it has now been fully restored, including all its detailed mosaics depicting biblical scenes and figures and framed within the building’s structural ornamentation.

Continuing on to the Peter and Paul Fortress, constructed by Peter the Great in 1703 as the primary defense from the threat of Swedish attacks on the new city, we encountered another architectural treasure. Within the fortress walls stands the Peter and Paul Cathedral, a baroque structure built in 1712 as the main cathedral of the new Russian Empire, as well as the burial site of the Romanov Dynasty. The gilded steeple of the cathedral can be seen from all surrounding points, including boats cruising on the Neva River, while two red towers adorned with galley heads function as oil-lit beacons for ships navigating the river.

Following a hearty Russian lunch of beef Stroganoff and rice, we crossed the Palace Square to reach the famed Hermitage Museum, which was the Winter Palace of the Russian Tsars from 1760 to 1917. The green-and-white three-story baroque palace extends along the northern boundary of Palace Square; to the south is the General Staff building, a two-story arch mounted by a Chariot of Victory. In the center of the square is the Alexander Column, commemorating Russia’s military victory in the war with Napoleon’s France. Named after Emperor Alexander I, the 83-foot-high red granite monolith is topped with a statue of an angel holding a cross. The city’s largest gathering arena, the square hosts parades and concerts; on the day of our visit, many flags fluttered in front of the General Staff building in honor of an international congress.

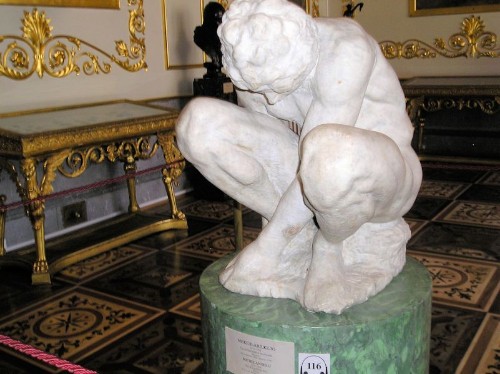

The Winter Palace has 1057 lavishly decorated rooms, which hold the bulk of the museum’s collection of over 3 million artworks. The collection, started by Catherine the Great with pieces bought en masse from European aristocrats, was embellished by successors, enriched by Bolshevik confiscations, and completed with works appropriated from conquered Germany at the end of WWII. It is said that a visitor spending a minute in front of each piece would take eleven years to view the entire collection, which ranges from ancient Egypt to the early 20th century, including Oriental treasures as well as masterpieces of European art, and reflecting the development of art through the ages.

Michael Angelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt, impressionist and post-impressionist masterpieces by Matisse and Picasso are in the most popular galleries. We went around with a local guide, who took us to the galleries she thought we should see, including the Large Throne Room, the Armorial Hall and the Gallery of the History of Ancient Painting. Favoring the Old Masters, we never got near the Impressionist or Post-Impressionist rooms. Fortunately, I had been to St. Petersburg in the 1980s during the Soviet period, when the museum was not as crowded, and still vividly remember standing in admiration for a very long time in front of Matisse’s wall-size painting, The Dance.

The rich cultural experience continued into the evening at the Mariinsky Theatre, home to Russia’s finest opera and ballet companies. The ballet, which started as an art form in Russia to entertain royalty, now attracts the masses. We watched Giselle in the beautifully decorated auditorium of the green-and-white neo-classical building dating from 1859. Giselle, a fantasy ballet in two acts, was a superb production; for two hours I was totally engrossed in the exquisite dancing of all the performers, especially the soloist in the role of Giselle. Tickets must be secured in advance to ensure good seats. Vita was able to get tickets for us by calling a friend in St. Petersburg while we were still in Vilnius.

On our final day we drove to Tsarskoe Selo (the “tsar’s village”), now part of the town of Pushkin 25 km south of St. Petersburg, to see Catherine’s Palace and Park. During the drive, Vita continued to educate us. Dynasties had collected money, which they spent to build Russia, each contributing to the country; they had a monopoly over the land, worked by serfs. The Bolsheviks, headed by Lenin, tried to destroy everything reminiscent of the past. They built monuments to honor their heroes and massive solid structures to show Soviet strength and stability. Sturdy apartment blocks stayed warm in the winter and cool in the summer. After Perestroika, people were given ownership of their apartments for free and sold them to others. Now all apartments are privately owned; it is prestigious to live in the city center. There is no space left in the city for private houses, which are built only in the suburbs.

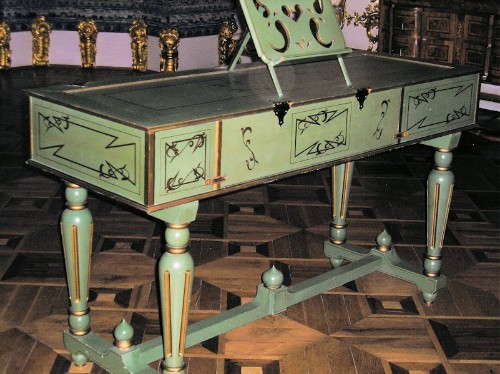

Catherine’s Palace in the countryside is a blue-and-white rococo building with a gilded stucco façade and statues on the roofline, dating from 1756. The summer residence of the tsars, the palace has a lavish interior, including the Marble Staircase, the Grand Hall of Mirrors, gold ornamentation throughout, formal dining rooms, period furniture, musical instruments, paintings, and a portrait gallery. The Amber Room, a famous chamber decorated in amber panels of different-colored mosaics backed with gold leaf and mirrors, has been restored, as the original panels were stolen during the occupation of Pushkin by Hitler’s army in 1941 and are still missing. The palace has a formal garden with cut alleys within the huge Catherine Park, home to a reflecting pool, two ponds and pavilions decorated with marble or bronze statues, and exotic trees.

Satiated with luxury and ostentation, we returned to the city. The final attraction of the day was a visit to St. Isaac’s Cathedral, which faces the eponymous square, with its central monument to Nicholas I on his horse. St. Isaac’s is the largest Orthodox cathedral in the city, accommodating 14,000 worshippers. Built over a period of 40 years the Byzantine-Greek structure, in its neo-classical rendering, dates from 1858. Flanked by four subsidiary domes, its large central dome, plated in pure gold, rises 333 feet and is decorated with twelve statues of angels. The internal features of the cathedral, such as its columns, pilasters, and floors, are composed of multi-colored granite and marble brought from all parts of Russia. Some of the biblical scenes and figures in the interior are painted; others are depicted in mosaic. The cathedral has a pair of bronze doors covered in relief.

Our memorable journey ended over a Farewell Dinner with fine Russian dining to the accompaniment of lively gypsy music and dance. The next morning I returned to Istanbul for another ten days, before returning home to the United States.