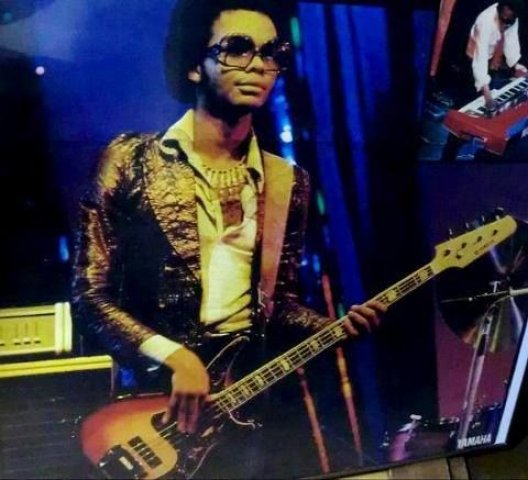

Bass Player Michael Henderson at 71

Played with Stevie Wonder and Miles Davis

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 25, 2022

It was fifty years ago when I first heard Michael Henderson with Miles Davis.

At 71 he died of cancer several days ago.

An autodidact he was on the road at fourteen where Stevie Wonder found him. He would be with Wonder for five years until Miles Davis “stole him.”

At the time Henderson knew nothing about Davis and asked a friend about him. He showed up where Miles was staying.

The next day he was in the recording studio. Miles was laying down tracks for the documentary film on the legendary boxer Jack Johnson.

I recall seeing the film during its theatrical release and marveling at its abstract sounding music. Miles, a lifetime boxer, was emotionally invested in the project.

Reporting about that session it’s stated that “Michael Henderson launches into an enormous boogie groove with (drummer) Billy Cobham and John McLaughlin (guitar). Miles immediately leaves the control room to join in with them. He achieved exactly what he wanted for the soundtrack by creating the effect of a train going at full speed (which he compared to the force of a boxer). By chance, Herbie Hancock had arrived unexpectedly and started playing on a cheap keyboard that a sound engineer quickly connected.”

It was a period of productivity and change for Miles.

Arguably the greatest jazz album ever Kind of Blue was recorded March 2 and April 22, 1959. A decade later, August 19 to 21, 1969, he recorded Bitches Brew a double album of electronic fusion.

That changed the face of jazz but was transitional and more of a beginning than an end. Throughout his career Miles hit many peaks and routinely created new paradigms but, no matter how successful and adored by fans, he had a pact with the devil to move on.

Jazz had become enshrined as an American art form and Miles would have none of it. The music had become formalized and academic. It was the era of Berklee College of Music with Max Roach and Archie Shepp teaching at U Mass Amherst.

Miles didn’t want to become fossilized as a “legend” like Dizzy Gillespie who evoked more nostalgia than relevance. To the end Miles remained a badass mofo.

The fans whom Miles famously turned his back on were dominantly white, aging and middle class. He wanted the audiences of James Brown, Sly Stone, George Clinton, Rick James and Marvin Gaye.

He made a chilling ballad of Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” In June, 1970, Miles opened for Laura Lyro for four nights at Filmore East. It is reported that despite low attendance Miles was well received. Nyro was a fan of Miles and Trane.

Michael Henderson gave him the funk he craved. It was the groove he built the band around.

In many ways Bitches Brew had been a patchwork quilt of riffs and post production splicing. The challenge was how to take that sound out of the studio and on the road.

Miles went all in on electronics but it was still a work in progress. Regular bass player Dave Holland transitioned from stand up to electric. He put pianists Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett and Herbie Hancock behind the early Fender Rhodes keyboards. Miles miked his horn and put it through wah wah pedals and later computer consoles.

I saw Miles often during that period but the music was never the same. Side men shuffled in and out. But a standard, for at least five years an eternity for Miles, was Henderson.

Looking back that first exposure proved to be the most paradigmatic and galvanic

It started at Harvard Stadium and the Sunset Series. The transition to Bitches Brew and funk had widened his appeal with rock producers. Miles was slotted in with a season which featured the last live appearance of Janis Joplin and British rockers Ten Years After.

Later that week Miles was booked at the road house Lennie’s on the Turnpike. It was always best to catch Miles in clubs where he could be heard intimately while he fine tuned and experimented with the music.

I recall being surprised by the young, skinny bass player. He was the pulse of a band of soon to be legendary players. That night the band featured Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett on keyboards. Guitarist John McLauglin, who recorded with Miles, was sitting in. I didn’t particularly care for Gary Bartz on reeds primarily soprano sax. He never held his own compared to Trane, Sam Rivers, Cannonball or Wayne Shorter.

Henderson laid down a sustained funk, ostinato beat. It was one long groove, with endless riffs and variations. Over that Jack DeJohnette added snare accents, high hat, and ride cymbals. Interestingly, the beat was led by bass and not drums. It was more primal and intuitive than cerebral. It was a constantly surging wave that the others musicians surfed and laid down solos over. Wherever they strayed he was always solidly there for them to lay back on.

There’s no document of what was heard that night other than what’s in my head.

Over the next few years, Henderson recorded albums with Davis, including “A Tribute to Jack Johnson,” “Live-Evil” and “On the Corner.” In a 1997 review of CD reissues of five Davis albums from 1969 to 1973, the New York Times critic Ben Ratliff cited “Live-Evil” and “In Concert: Live at Philharmonic Hall” as evidence of Henderson’s noticeable impact on the band.

“Henderson made Davis’s band sound less searching, more hypnotic,” Ratliff wrote. “Instead of improvising and interacting with the band, he took a simple bass vamp and percolated it endlessly.”

That was the opposite of what bass playes Jaco Pastorius told me when Weather Report was formed in 1976 with Wayne Shorter and pianist Joe Zawinul. “We all solo all the time.” With the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Return to Forever they overtook fusion which Larry Coryell and Miles Davis had started.

When Henderson left Miles in 1976 he joined jazz drummer Norman Connors for whom he sang ‘Valentine Love” then for another album “You Are My Starship.” He also recorded twice with Phyllis Hyman and had a seven album contract with Buddah Records.

He had singles like “Take Me I’m Yours,” which hit No. 3 in 1978; “Wide Receiver,” which peaked at No. 4 in 1980, and “Can’t We Fall in Love Again,” a duet with Hyman that rose to No. 9 in 1981.

After seven albums for Buddah, the last of them in 1983, he recorded “Bedtime Stories” for EMI America in 1986. That was his last solo album, although he continued to perform.