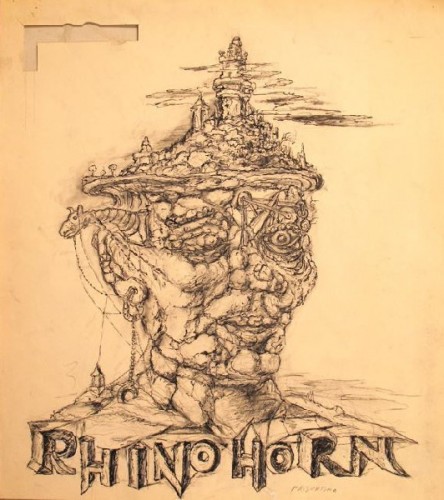

Re-Introducing The Rhino Horn Group

Evolved from Figurative Expressionism

By: Adam Zucker - Jul 24, 2014

“Our art is involved with life; it is concerned with humanity, with emotion. We will not listen to explanations from or about the technically minded artist of yesterday. Just as abstract expressionism - the art of the fifties - was superseded by pop, op, hard edge, minimal and color field the art of the sixties - so now a new art, a humanistic art, will characterize the seventies.” From the Rhino Horn manifesto.

In 1969, The Rhino Horn Group was founded in New York City by a group of artists bound together by their dedication to figurative art and a collective notion that artistic practice should have both a critical and a social function. They critiqued the art-as-business ideology that absorbed fine arts into consumer culture in the United States during the 1960s.

The seven founding members were Peter Passuntino (b. 1936), Benny Andrews (1930-2006), Jay Milder (b. 1934), Peter Dean (1934-1993), Ken Bowman (1937-2014), Michael Fauerbach (1942-2011), and Nicholas Sperakis (b. 1943). Between 1969 and 1978, active members also included Bill Barrell (b. 1932), Leonel Góngora (1932-1999), Isser Aronovici (1932-1994), June Leaf (b. 1929), and Joseph Kurhajec (b. 1938). In addition, Rhino Horn included exhibiting guest artists Christopher Lane (b. 1937), Red Grooms (b. 1937), and Lester Johnson (1919-2010).

Although each of the artists in the group had their own personal expression in their work, there was a collective emphasis on depicting the human condition as subject matter, criticizing social ills and cultural myopia, and encouraging a range of emotional responses.

The significance of Rhino Horn’s history being acknowledged is to map out an alternative art historical account of the period following Abstract Expressionism (the end of Modernism) and the era regarded as Postmodernism. The existence of Rhino Horn (throughout the 60’s and 70’s) contradicts the narrative in many art historical texts that Neo-Expressionism in the late 1970s was the return to mythological, audacious and boldly charged figurative painting. It underscores a lineal continuity of American Figurative Expressionism from the 1950s onward.

A majority of Rhino Horn’s founders evolved from the Post War American Figurative Expressionist movement. This entailed a reaction to Abstract Expressionism that flourished simultaneously in Provincetown, New York City, Chicago, and the Bay Area of San Francisco. When Figurative Expressionism faded as a viable entity during the 1960s, the members of Rhino Horn reinvigorated this style with elements of the grotesque and imagery derived from mystical and mythological traditions.

Figurative Expressionism never received the critical support accorded to Abstract Expressionism. The divergent movement was cut short when curatorial attention shifted from Expressionism to less physically emotive styles of Minimalism, Hard-edge painting and Pop Art. When Pop Art came to dominate the art market and mass-media, some figurative artists explored ways to remain distinct from more commercial pop trends. Some artists pursued solo careers, but others formed alliances and exhibited as groups. In Chicago artist groups included the Monster Roster, Imagists, and The Hairy Who. On the West Coast, there was the Underground Comix movement and the Kustom Kulture scene. In New York there was the No! Art Movement and the Rhino Horn Group.

Over and above the use of figuration, these groups shared an assertive and confrontational approach to art, in which they sought to expose the darker side of humanity, the complacency, coarseness, and banality of contemporary life through poignant and often grotesque imagery.

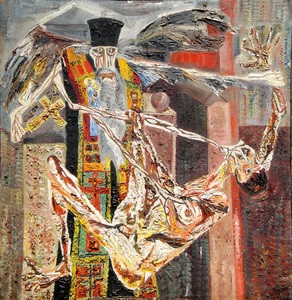

The Rhino Horn members regarded themselves as a humanist art collective. This aspect of their work was even more central to their identity than the use of expressionism. It was the combination of these elements, however, that was most responsible for the artistic cohesiveness of the group. The members wanted to expose the absurdities of racism, war, organized religion, and mass consumerism. Their strength as a movement lay in a collective humanist ideology.

A number of recurring themes can be traced across many of the works of the Rhino Horn artists. One example is the trope of poverty and social class. Andrews’ work reflected his perspective as an African American on such themes as war, racial segregation, and the experiences of common people in their work and leisure activities. Andrews encountered so many homeless individuals on the street outside his studio on Manhattan’s Lower East Side that local poverty made an even deeper impression on him than it had in the rural South or urban Chicago. His early collages, such as "Beggar Man" (1959), reflect the gritty appearance of life on the streets of lower Manhattan.

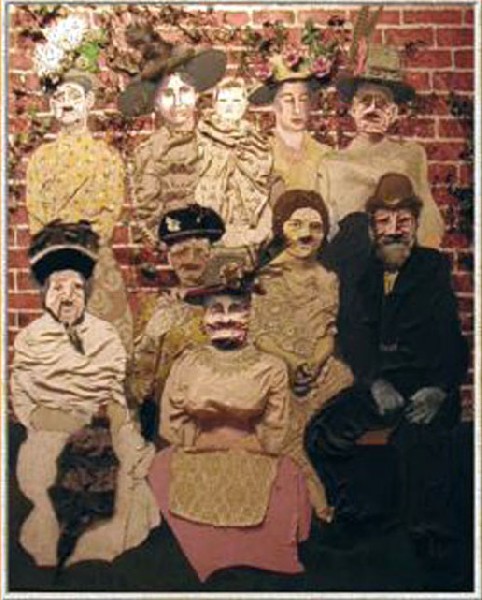

Downtown streets also inspired Barrell. In a Rhino Horn exhibition at the Cranford Tomassula Gallery at Union College in Cranford, New Jersey (1978), he exhibited a series of collages and paintings that featured the textures and objects (trash and neglect) of city streets. Similarly, Bowman’s collages used materials from the streets, such as tattered rags, and presented imagery that reflected the struggle of the typical working-class American family.

Milder used the subway and urban culture as settings for mystical subjects by conflating psychology of the unconscious mind and the esoteric teachings of Kaballah to Old Testament tales. It was through this philosophical and spiritual process that he combined contemporary life with pre-history. Living and working on the Bowery and Lower East Side, influenced Sperakis to create a series of works (paintings and woodblock prints) centered on the despair of the homeless. The impersonal and overbearing nature of the urban environment can be seen reflected repeatedly in the sculptures and paintings of Fauerbach.

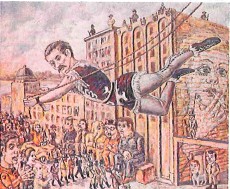

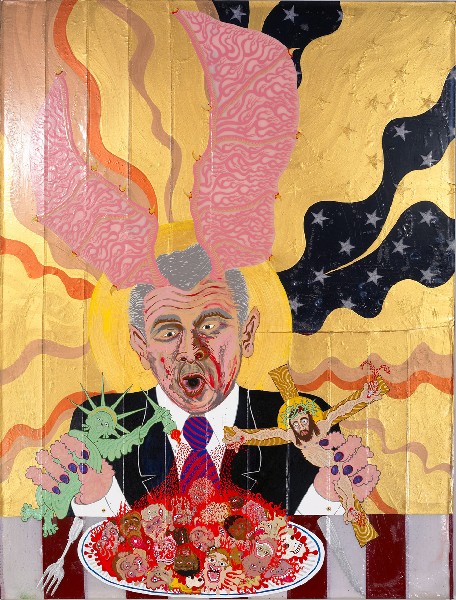

Another common theme in the work of the Rhino Horn artists was a strong rejection of war and violence. Passuntino created hauntingly graphic images of the spoils of war, while Andrews created allegories illustrating the physical and psychological effects of modern warfare on ordinary folks. Dean’s burlesque paintings satirized American military and domestic exploits—in particular those associated with the Vietnam conflict and the social injustice of authority during the Civil Rights Movement.

As a whole, the Rhino Horn Group variously depicted the aggression and oppression imposed by corrupt individuals, religious orders, and governments. June Leaf, the only female member of Rhino Horn produced powerful images of archetypical women and cartoonesque scenes of domesticity. Leaf and Nancy Spero (a friend of the Rhino Horn Group along with her husband Leon Golub) paved the way for feminist artists, although neither of them have received acknowledgement for doing so.

Retrospectives have served to remind the public of the work of The Hairy Who, the Underground Comix movement, and the No! Art movement. The contributions of the members of Rhino Horn, however, are less well known. Overall the group has been ignored in discussions regarding the figurative art of the 1960s and 1970s.

What have been overlooked are links between their work and the better-known Neo-Expressionism of the 1980s and their non-inclusion in critical exhibitions centered on humanist art. A re-examination of Rhino Horn is key to an essential account of contemporary of American Figurative Painting.

Was the work of the Rhino Horn members, for example, merely a sideline, a curious and perhaps somewhat interesting irrelevant movement? Exhibition history might appear to suggest that this was the case.

Although Rhino Horn had not yet been founded, all seven of the original Rhino Horn artists were known to so-called experts in contemporary art when Robert Doty (1933-1992) curated an exhibition entitled “Human Concern/Personal Torment” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1969. None of the founding members were included (June Leaf who briefly exhibited with Rhino Horn in the mid-70s was included). The exhibition presented itself as a renewal of Peter Selz’s 1959 influential MoMA exhibition “New Images of Man.” Its focus on works that used challenging imagery to explore the theme of contemporary society’s callousness toward civilization would seem appropriate for the inclusion of the Rhino Horn artists.

Their exclusion is all the more striking given that five years later Barry Schwartz discussed all seven of the founding members of Rhino Horn, as well as June Leaf and Leonel Góngora, alongside most of the artists included in Doty’s exhibition in his book, "New Humanism: Art in a Time of Change." When Doty still did not include the Rhino Horn artists in his 1973 exhibition, “Extraordinary Realities”, Lawrence Campbell (1914-1998), editor of ARTNews, expressed shock at their exclusion. Doty focused on works by members of the Chicago Imagist movement of the 1960s and by artists associated with the San Francisco Funk Art movement of the 1950s. The Rhino Horn artists clearly shared essentials with both these movements, yet their exclusion from these shows further clouded their legacy.

The rise of Neo-Expressionism in the late 1970s and 1980s may also have had a hand in obscuring the Rhino Horn Group’s legacy. Neo-Expressionism was an international movement in painting and sculpture. Prominent American painters among Neo-Expressionist artists included Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), David Salle (b. 1952), Eric Fischl (b. 1948), Julian Schnabel (b. 1951), Susan Rothenberg (b. 1945), and Chuck Connelly (b. 1955). Other notables included the Germans Georg Baselitz (b. 1938) and Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945), and the Italians (known as the Transavanguardia) Francesco Clemente (b. 1952), Sandro Chia (b. 1946), and Enzo Cucchi (b. 1949).

Like the artists of the Rhino Horn group, the Neo-Expressionists “returned” to portraying recognizable figurations, in contrast (and partly in reaction) to both Pop Art and Minimalism and to the bulk of Post-Modernist art, which was essentially a continuation of these esoteric schools.

Similarly to the Expressionists who returned to figurative painting during the post-World War II era, the Neo-Expressionist movement of the 1980s was very broad. The artists who were associated with this movement were diverse in both their ideologies and their methods. However, a core group of key influences and predecessors are commonly cited in textbooks. These include post-WWII artists such as Francis Bacon and Leon Golub, as well as the New Image Painters of the late 1970s. Philip Guston’s use of figuration beginning in the late 1960s, which was shaped by cartoon imagery, social realism, and action painting, also was an important influence on Neo-Expressionism.

Of all their influences and analogues, however, the Neo-Expressionist painters’ use of mythic subjects and of a variety of media and painterly styles aligns their work most closely with that of the Rhino Horn artists.

This significant proximity has not gone completely unnoticed. In a New York Times review of a solo show of Jay Milder’s paintings in 1988, the critic Vivian Raynor wrote that “Even when figuration began trickling back in the early 1970s, Mr. Milder, who by that time was part of the ‘Rhino Horn’ group, was still on the wrong side of the fashion fence…. Mr. Milder is an Expressionist—one of several—who has remained visible despite his lack of careerism. It is time that someone looked into his case, if only to prevent the more-driven art scholars from re-launching him as a ‘father’ of Neo-Expressionism.” Unfortunately, it has taken over 30 years since someone has "looked into the case " of Milder and the rest of the Rhino Horn Group.

Another interesting and perplexing difference between Rhino Horn and their Neo-Expressionist predecessors was that the latter group was immediately swept up and championed by some of New York Cities top galleries. It seemed that Rhino Horn was ill timed by emerging a decade too soon. Rhino Horn responded to art world indifference by creating their own opportunities exhibiting in galleries they created and ran with friends. The artists who were inspired by Provincetown’s now legendary Sun Gallery and Hansa Gallery of New York City’s “Tenth Street” scene ran many of these galleries.

One of these alternative ventures, the City Gallery, was founded in 1958, inside a Flat Iron loft at 24th Street and 6th Avenue that Grooms and Milder shared. The artists who exhibited at the City Gallery included Bob Thompson, Christopher Lane, Passuntino, Andrews, Gandy Brodie (1924-1975), Wolf Kahn (b.1927), Emilio Cruz (1938-2004), Bob Beauchamp (1923-1995), Norman Bluhm (1921-1999), Mimi Gross, Lester Johnson, Stephen Durkee (b. 1938), Robert Whitman (b. 1935), and Alex Katz (b. 1927).

Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929) and Jim Dine (1935), who would both become influential in the Pop Art movement, were given their first New York solo exhibitions at the City Gallery. After Oldenberg was rejected by the artist run Phoenix Gallery, Grooms and Milder dropped out of the Tenth Street gallery scene and invited Oldenberg to exhibit in their space. Grooms recalled, “We were reacting to Tenth Street. In '58 and '59, Tenth Street was sort of like SoHo is now, and it was getting all the lively attention of everyone downtown….We were just kids in our twenties, [but we] had a flair for attracting people to our openings.”

The City Gallery was a twenty by forty foot, third-floor loft space above a men’s clothing store in the Flat Iron District. Here, Milder, Grooms, and friends lived and worked. They used the space as a studio by day and hosted parties and exhibitions at night.

In 1959, the City Gallery’s operations expanded downtown, to a third floor studio loft run by Grooms, Milder, and Bob Thompson at 148 Delancey Street (at the corner of Suffolk Street) on the Lower East Side. The new gallery would become known as the Delancey Street Museum, an early site for Grooms’ “happenings” like "The Burning Building" (December 4 to 11, 1959), which featured a cast of Grooms, Milder, Barrell, Thompson, Joan Herbst, and Sylvia Small.

The final collaborative stage before the formation of Rhino Horn took place in a third gallery space. The St. Marks Place Gallery in a Lower East Side loft was located at 12 St. Mark’s Place. The gallery was operated by Passuntino, Milder, Barrell, and Lane. It hosted poetry readings and film screenings as well as exhibitions and “happenings.”

On March 26th, 1967, the St. Marks Place Gallery organized a tribute to the seminal Figurative Expressionist Bob Thompson, who died in 1966 at the age of 29. The exhibition featured the paintings of Thompson and his colleagues including Andrews, Milder, Passuntino, Lane, Grooms, Dean, Barrell, Sperakis, Johnson, Beauchamp, Kahn, Robert De Niro, Sr., Mimi Gross (b. 1940), Gandy Brodie, Emilio Cruz, George Segal (1924-2000), Mary Frank (1933), Alex Katz (b. 1927), Larry Rivers (1923-2002), Emily Mason (b. 1932), and others.

In the late 1960s, the Lower East Side was a rough neighborhood. Here, the St. Marks Place Gallery and others like it provided artists with affordable space. Despite the rough neighborhood, these loft-space galleries attracted large crowds. Passuntino, Lane, Barrell, and Milder recall that the openings were popular and well received among the Downtown scene. Running a gallery, however, was time consuming and cut into their studio time. The gallery did not last long but led to the creation of Rhino Horn.

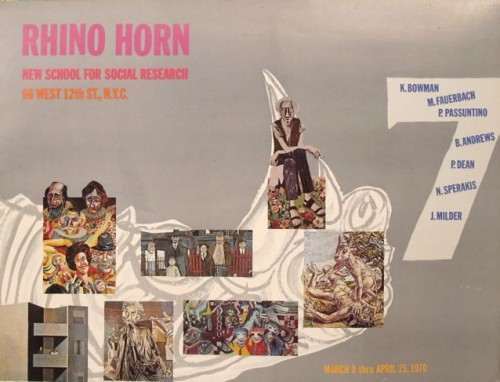

The original seven Rhino Horn artists (Andrews, Bowman, Dean, Fauerbach, Milder, Passuntino, and Sperakis) planned their inaugural show with a budget of $300 per person. Andrews was teaching at the New School for Social Research and secured the school’s Wollman Gallery at 66 West 12th Street for the inaugural show that opened on March 9th, 1970. Passuntino created the artwork for the posters, and a friend of Milder’s, Norman Shaefer, printed the exhibition catalogue.

A viewer at this inaugural show was bombarded by Rhino Horn’s bold, emotive, figural imagery. The Rhino Horn artists expressed the discontent, turmoil, and emotion of the 1960s. The members strove to be as outrageous as possible. The strong and concerned imagery in their work was intended to promote social and political dialogue.

It certainly was not what was happening at the galleries where one would go to view art stars. During a time as outcasts in the mainstream art world they were intent on making their presence felt. Just a few days before the inaugural Rhino Horn exhibition the Weathermen (later renamed the Weather Underground) carried out a terrorist attack in a townhouse across the street from the gallery.

The show at the New School was “raucous” in a socially conscious manner according to art critic Peter Schjeldahl, who reviewed it in the New York Times. His article “A World of Raucous, Challenging Images” noted the marginalization that Figurative Expressionism had experienced over the previous 30 years. He wrote that the exhibition was successful in “making a case that simple justice should have made long ago.”

Schjeldahl called the Rhino Horn exhibition an optimistic beginning for a contemporary revival of Figurative Expressionism. He suggested that the group consider including Christopher Lane and Bill Barrell, who had established themselves as part of the Second Generation of American Figurative Expressionism. Regarding the prevailing apathy for Figurative Expressionism Schjeldahl wrote that “It would be too bad if the uptown art world, attuned to parochial (though legitimate) standards of beauty and formal rigor, continues to ignore the real merit of painters whose swirling pigment and raucous images are among the most challenging pleasures of art in New York today.” In keeping with Schjeldahl’s suggestion, Rhino Horn later included Barrell. Leonel Góngora was also invited to join the group.

In 1974, when Rhino Horn’s short yet prolific run had reached its halfway point, five of the group’s members (Andrews, Dean, Milder, Góngora, and Sperakis) exhibited their work at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. To date this has been the only museum scale exhibition of the group. The show was described by Dick Cossitt, the art editor for the Virginian-Pilot, as “Surreal Expressionism, a mode of painting more allied with European sources like Soutine and Ensor and Dubuffet than anything in New York.” Cossit, who noted affinities between the group and Chicago’s The Hairy Who, described the works in the exhibition as “extremely noisy things, aggressive statements absolutely bleeding with concern for the human condition.”

As the group’s inaugural manifesto states, “Our art interprets and respects the viewer—not his products, not his technology. If the mirror we hold is too revealing, the image too harsh, the fault, dear Brutus, lies in yourself.”

How the viewer interprets and respects the Rhino Horn Group remains to be seen. Despite the fact that some critics, most notably Hilton Kramer, responded to their humanist/figurative enterprise by seeking to turn them into artistic and perhaps even social pariahs, they chose the name Rhino Horn for a reason. They were thick skinned and the fact that they were at odds with the art world seemed to fuel their moral obligation of depicting the reality that they perceived.

It proved impossible to deflate their enthusiasm altogether or to prevent them from having an impact (albeit a small one) on the artistic scene in America during the late 1960s and 1970s. Their status, however, may be overdue for a reappraisal.

Just as the Figurative Expressionism practiced by the Rhino Horn artists was not without antecedents this movement did not fade out or “dead end.” Figurative painting as well as socially engaged work is at a high point in today’s art world. One may consider the work of Aaron Johnson, Chris Ofili, or Swoon and confirm that the aura of Rhino Horn continues.