Every Breath You Take

I Can See for Miles

By: Cheng Tong - Jul 22, 2022

The major skills I teach at Blue Heron Stillness are qigong, taiji, and meditation. They all share one thing in common: the breath.

Qigong exercises and taiji forms, both breath-driven, move at the pace of the breath. We begin each from a posture of stillness – wu wei – as we focus our attention on our breath, noticing its pace, and we match the movements to it.

Wu wei can be translated as nothingness, absolute yin, or absolute stillness. But the translation I favor is “not forcing.” Simply being, just breathing.

We do not change the breath to match the movements – we change the movements to match the breath. We want to be breathing at the conclusion just as we were breathing before we began.

During meditation, or as we call it, “sitting still, doing nothing,” we focus our attention on our breath. As thoughts insinuate themselves into our mind, we just remind ourselves to return to the breath and allow the thoughts to drop off. After all, they were only thoughts and did not exist anywhere else in the universe except in our mind at that moment.

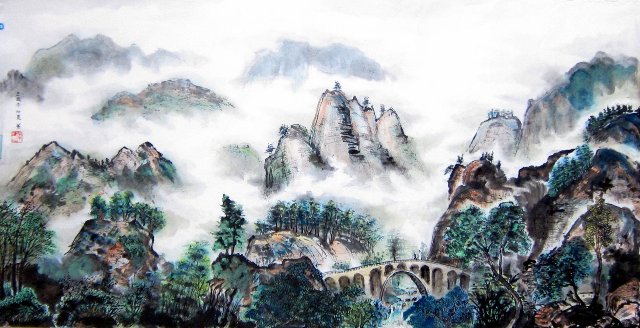

When the Abbot gave us a few days off at the temple one time, I chose to go off the mountain and take a bus to Wudangshan. A small city (by China’s standards) sits at the entrance to Wudangshan; there, you can board a bus that will bring you up into the Wudang Mountains to the base of Wudang Mountain proper.

Wudang is the center of Daoism in the world, where the early monks went to hide from the Emperor’s soldiers. The Chinese emperors were fearful that the people would follow the Daoist priests and monks instead of them, and they killed many of them, destroying thousands of temples over the centuries.

I took the bus ride up into the Wudang Mountain range and climbed the 5000 steps to the top. While there is a cable car that will bring you about halfway up, I had gone there as a worshiper. I wanted to experience what the early monks had experienced, and so I climbed.

When I arrived at the summit and looked out at the mountain range that extended many miles both east and west, I was gobsmacked. The beauty was beyond my comprehension, powerful, poignant, and pulsating almost imperceptibly. I believed that if I stood there long enough, cultivating my stillness to its extreme, I would even be able to hear the mountains breathe.

Yet I knew I was a Padawan, so to speak, a grasshopper, by comparison. The mountains were eternal, and the whole of my entire life was merely a brief instant in their lives.

At that moment, though, I vowed to up my game and to work harder to cultivate my stillness. I am in the northern Berkshire mountains now, surrounded by another kind of beauty. Powerful, poignant, and pulsating at their own rhythm, the mountains here are also breathing, but their inhales and exhales, just like in Wudang, last for centuries, at the very least.

Ever so soft, so slow, and smooth. And eternal. I took comfort in knowing that and the beauty of what was before me as I took in the totality of the experience. I lingered on that precipice for a solid hour before I gave any thought to climbing down those 5000 steps.

I will never be able to see the mountains breathe, of course. But I have kept my vow, and continue to cultivate my stillness each day. I do so by focusing my attention on my breath, whether I am sitting still, doing nothing, or playing taiji. I carry that stillness with me everywhere I go, and when my students or friends tell me of a difficulty they are experiencing, my response is always the same:

Just breathe. Breathe like the mountains . . . long, slow, and deep. The breath is eternal.