Daphne with The Cleveland Orchestra

Welser-Möst Realizes the First of the Last Great Works of Strauss

By: Susan Hall - Jul 19, 2015

Daphne

The Cleveland Orchestra

Music Director and Conductor Franz Welser-Möst

Composer Richard Strauss

Librettist Joseph Gregor

Lincoln Center Festival

Avery Fisher Hall

New York, New York

July 18, 2015

Regine Hangler, soprano (Daphne); Andreas Schager, tenor (Apollo); Norbert Ernst, tenor (Leukippos); Nancy Maultsby, mezzo-soprano (Gaes); Ain Anger, bass (Peneios).

It was easy to imagine Daphne in the garden as Regine Hangler, of sumptuous voice, introduced herself in a gorgeous monologue. We are shown a vocal line which might have been written for a string instrument, but it is in the voice. An oboe joins the pastoral opening.

Strauss himself had worked hard to humanize the characters, knowing well that dry, academic figures from the past would be impossibly difficult to bring to life in music. Gaea, sung with a mother's love and concern by mezzo Nancy Maultsby, and her daughter sing of earthly life early on.

Without seeming in the least formulaic, there are big vocal set-pieces: the feast of Dionysus, the Apollo-Daphne love duet which ends in dark harmonies of a kiss. The clear lament for Daphne's earthly lover is bolstered by the orchestra matching the pure tones and often exceeding them.

Apollo's final aria as he departs is a stunning monologue sung with clarion purity by Andreas Schager.

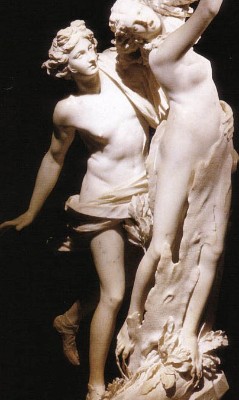

Daphne is the first of the last of Richard Strauss' compositions. In it, he moves into the lustrous harmonics and melodies with which Strauss celebrates art's place in life.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Strauss' long-time collaborator had died, and in this opera, he joined forces with Joseph Gregor, who Strauss' wife accurately pinned as more academic than dramatist.

Strauss struggled with Gregor, but found himself relying on the general manager of the Vienna Opera, librettist Stefan Sweig who had to flee Nazi Germany, and conductor Clemens Krauss to assist in a satisfactory structure. Gregor, forinstance, wanted to have the chorus sing at the conclusion, but Krauss said it was crazy to have anyone sing after Daphne is transformed into a laurel tree.

While the Concert Chorale of New York added immeasurably to the evening's pleasure, Krauss was correct.

Some have said Strauss became an extinct volcano as he worked to save the Jewish members of his family from concentration camps and death. Yet here, in the beginning of the last period, you can hear new tones and harmonies. Pianist Glenn Gould and cultural historian Edward Said find continuing virtuosity and even "a third revision of the tonal system."

Welser-Möst deliciously drowns us in the score until the moment Daphne freezes and becomes a tree. At this moment, dividing Daphne's human life from her arboreal one, Welser-Möst stops. We sit at first in stunned silence, and then the orchestra lavishly heralds her transformation. There is no more singing.

The conductor has a gift for making the lyric beauty of the music sing in the orchestra. Yet texture is translucent, with unobtrusive but defining punctuation and soaring phrases.

Strauss played nothing but the finale of Daphne on his piano at home during the last year of his life. The interplay of counterpoint, the beautiful melodies, harmonic pacing and masterful orchestral sound as performed by the Cleveland Orchestra show us why.