Greene & Greene at Boston Museum of Fine Arts

A New And Native Beauty Expressed in Art and Craft

By: Mark Favermann - Jul 16, 2009

A New and Native Beauty: The Art and Craft of Greene & GreeneAt the Museum of Fine Arts

465 Huntington Avenue

Boston, MA 02115

July 14, 2009 to October 18, 2009

617-267-9300

www.mfa.org

With a wonderful catalogue edited by Edward R. Bosley and Anne E. Mallek

Like sipping a fine, rare richly-made wine, the current exhibit A New and Native Beauty: The Art and Craft of Greene & Greene exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is a superb visual taste of two authentic American Arts and Crafts masters. As the brothers Greene, Charles and Henry, worked primarily in California, the distinctive objects and houses shown add up to a very special show of work that is rarely seen in the East. Here is the "gold standard" for Arts and Crafts style design. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is one of the ten greatest comprehensive museums in the world. The expectation of any exhibition is that it will be of the highest quality. This current architecture and design show underscores this distinguished MFA tradition. This is exquisite design shown in a most clear, concise and elegant way.

The American Arts and Crafts Movement grew out of the writings and philosophy of British theorists John Ruskin and William Morris. Their approach was a reaction to industrialized society. It was based in an anti-mass produced and thus anti-machine made design that they felt was dehumanizing and produced dishonest products. Instead, they took as a model handcraftsmanship as exemplified by Medieval Guilds and the products produced by guild members. Thus, the creation of elegantly often simply enhanced but practical everyday objects was the desired goal. According to MFA Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts, Sculpture and Art in America Nonie Gadsden, "The Arts and Crafts Movement was not a specific style, but a philosophy about a way of life in which art played an integral role."

This philosophy was attractive to many prominent and influential Boston architects, designers, educators, arts patrons and craftspeople. The group included General Charles Loring, the first director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Charles Eliot Norton, the first art history professor at Harvard University who was a friend of Ruskin's, collectors and MFA trustees William Sturgis Bigelow and Denman Ross among others. Architect H. Langford Warren who founded the architecture program at Harvard University was its first Desn of Architecture. He was a major exponent of Arts and Crafts in America. Warren worked under H.H. Richardson before setting up his own practice. This Boston group went on to form The Society of Arts and Crafts in 1897. They pledged "to develop and encourage higher artistic standards in the handicrafts." This was to be done through mentoring, education and exhibitions.

Some of the Arts and Crafts advocates focused upon fostering its use for social reform including establishing utopian artist communities and craft training for immigrant girls. an interesting example of this is Boston's Paul Revere Pottery provided income for Italian and Jewish immigrant girls in the form of the Saturday Evening Girls club that was formed in 1899. Their inviting painted pottery and tea sets are shown today at the MFA and highly prized by collectors.

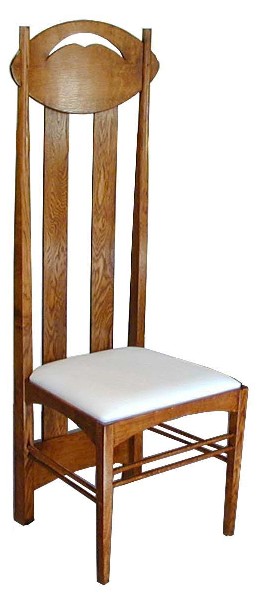

Regional variations of the Arts and Crafts Movement can be seen by Gustav Stickley's furniture and utopian United Crafts Workshops in Eastwood, NY and architect Ralph Adams Cram who drew upon medieval European styles. Cram designed many buildings at Princeton University and Boston's Roxbury Latin School. Others in the Northeast were inspired by Colonial Revival style. Architects and designers in the Midwest developed a rectilinear asymmetric, aesthetic that promoted simplicity and harmony with the landscape. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie school espoused this approach that included a total unification of architecture and design that included a distinctive horizontal design that used color, texture and repetitive patterns in a natural setting. Greene & Greene helped shape the California Arts and Crafts Aesthetic integrating the region's Spanish and Mexican legacy into their designs. Greene & Greene were known for their regionally inspired "bungalows."

Boston and the Northeastern United States became a center of intellectual thought on Arts and Crafts philosophy even though stylistically regional variations arose throughout the country. Prior to the more formal establishment of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Henry Hobson Richardson's Trinity Church in Boston's Copley Square was a clear predecessor. Richardson designed a modernized version of a Medieval Romanesque structure while collaborating with highly skilled artists and craftsman to create the exquisitely unified interior spaces, details and spaces set a standard for the future. Today, Trinity Church is still considered one of the most beautiful and visually unified buildings in Boston.

Adhering to a design philosophy of the creation of useful beauty or beauty with a purpose, the architecture and decorative arts designed by Charles Sumner (1868-1957) and his brother Henry Mather Greene (1870-1954) are now recognized as among the absolutely best work of American Arts and Craft Movement. The Greenes' work demonstrates a careful consideration of every building, furniture and functional object detail that they created. This included thoughtful references and consideration for geographical setting, climate, landscape and lifestyle along with particular sensitivity to natural setting.

Born in Cincinnati, OH, the Greene brothers' formative experiences were as teenagers at the progressive Manual Training School at Washington University in St. Louis. They went on to later complete their academic studies at M.I.T. and their early career professional apprenticeships with various Boston architectural firms set the groundwork for their later innovative and elegant style. Interestingly, prominent exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts of Japanese prints and decorative objects also had a strategic influence on their work. The Greenes were known to often visit the MFA when it was located in Copley Square. M.I.T. was then located nearby in Copley Square as well. They also took drawing and water color classes at the MFA. It should be noted that many of the architects that the Greeenes worked for were themselves former employees and apprentices to Henry Hobson Richardson. So, this master's philosophy was part of their training.

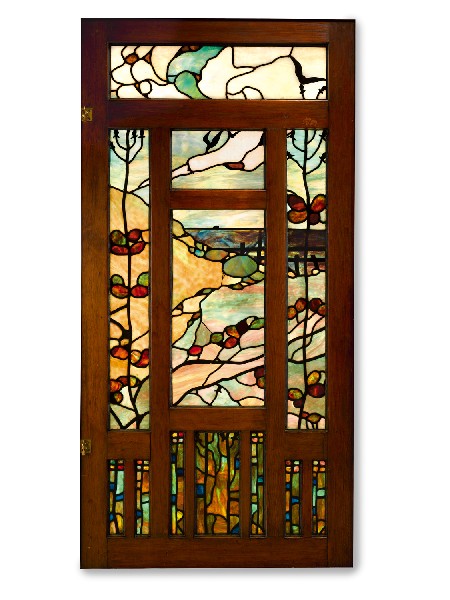

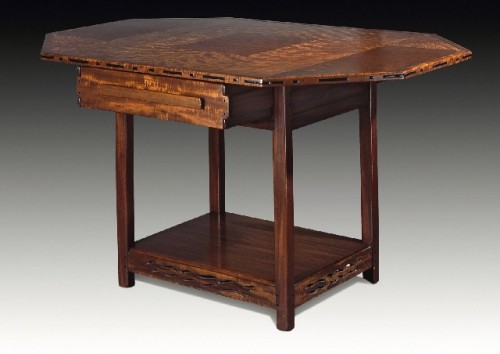

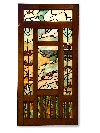

This enticing exhibition commemorates the legacy of the brothers' most productive period that included distinguished architecture and decorative arts objects and furniture. Highlights of the exhibition include exquisitely inlaid furniture, furniture crafted in exotic hardwoods, colorful but retrained stain glass and extraordinarily elegant metalwork and fittings. Architectural and furniture drawings as well as period photographs are also on view.

The impetus for this exhibit has been the centennial of the Gamble House in Pasadena, California. Greene & Greene designed it in 1907-09. The Gamble house is the pinnacle of Greene & Greene design. The Gambles were the visionary and sophisticated family that owned the huge Proctor and Gamble corporation. In 1966, heirs of Cecil and Louise Gamble donated the house and its furnishings (all by Greene & Greene) to the City of Pasadena and to the School of Architecture of the University of Southern California (USC). It is also the best preserved and most comprehensive example of the Greenes' major work. The house is now operated as a historic site and research facility. It is open to the public for tours. In 1980, a permanent exhibition of Greene and Greene decorative arts was opened at the Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art at San Marino, California.

If there is a conceptual laying on of hands in the Arts and Crafts Movement, the Greene brothers probably were influenced significantly by Scotsman Charles Rennie MacKintosh whose work influenced many European designers as well. In fact Charles and his wife traveled to Great Britain and throughout Europe visiting many architects and designers and viewing their built projects. Even Frank Lloyd Wright acknowledged their work, although he tried to credit himself for influencing them rather then perhaps the other way around. Design and architecture was widely published and read as well as studied in that period. So, architects and designers were knowledgeable about contemporary work if they were interested.

With clear Boston and New England ancestors and relatives as their individual middle names suggest (Boston Brahmin names Sumner and Mather), the Greene Brothers attended MIT's school of architecture together. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology's architecture program was the oldest and then most prestigious formal school of architecture in the United States. The Greene's grandfather had been an architect as well. Though living in the midwest, their parents had schooled both of their sons at experimental and practically-oriented secondary schools. Though the family was not wealthy, they had a sophisticated upper class attitude toward education and training of their children. Charles and Henry were certainly fostered by their parents to achieve creatively.

After three years of training at MIT, receiving only a certificate of architecture study, not a degree, the brothers decide to start their practical training for their professional practice by apprenticing to established small firms. Gentleman often did not complete degrees, but took enough courses and study to develop skills. This seems to be particularly true of engineers and architects in the late 19th and early 20th Century. Frank Lloyd Wright was notorious for bragging that he did not receive a degree in architecture, distaining university training over much of his career. Actually, he attended the University of Wisconsin for almost three years taking primarily engineering courses. The Greenes resided in Boston from 1888 to 1893. After that they moved to California to start their own practice.

This exhibition includes 120 objects that showcase the range and quality of materials that Greene & Greene worked in collaboratively with some of the finest artisans and craftsman in California. The exhibition is presented chronologically featuring 25 of the brothers' best known commissions. The first gallery examines the influences of the Greenes when they were in Boston including Japanese decorative objects with ceramics, metal work and prints. at the time of the Greenes' residence in Boston, the MFA had put together the most extensive Japanese collection in the West. Clearly, there was a strong almost pervasive Japanese influence on the Greene & Greene refined style.

The second section of the show explores the peak years of the Greene brothers collaboration. Objects demonstrate their unique design vocabulary, their use of traditional, spare but sometimes decorative wood joinery as well as their interest in metal as structure and form-giver. These added to the creation of the very California aesthetic that seemed to reflect the climate, landscape and available materials while underscoring the lifestyle of the client/owner. Every detail, structural elements, fenestration, light fixtures, textiles, furniture and tiles were part of an aesthetic whole, a unified work of art.

Unlike their contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright, Greene & Greene gave credit to their collaborating craftsman. California-based firms like that of furniture makers Peter and John Hall were not only credited, but were truly part of the Greene & Greene design team. As shown in this exhibit, the Halls were pushed through the vision of the Greenes to fabricate some of the finest pieces produced during this period. These pieces of furniture are treasures in themselves.

Yet, their architectural and design collaboration lasted only a few years. The Greenes only worked together from 1894 until 1916. They went their separate ways. Charles was a dreamer, the artist, who joined an aesthetic and spiritual community. Henry was the more practical one, but needed Charles' aesthetic vision. The exhibit's third gallery shows that the two were much greater together than either one alone. The firm Greene & Greene was dissolved in 1922. Their designs fell out of fashion, but were rediscovered and eventually honored after WWII. In 1952, they were cited by the American Institute of Architects as pioneers in modernism. Sadly, only one of the brothers was healthy enough to attend the ceremony. Since that time, the work of Greene & Greene has been venerated and held up as the standard for unified beauty.

This is an exhibition that should be appreciated by those who admire great architecture, great design and excellent craftsmanship. This is a visit to a golden standard of American Arts and Crafts, unified design and brilliant collaboration. Here is simple elegance justified by beauty and purpose, function and form at its most appealing. This show should not be missed.