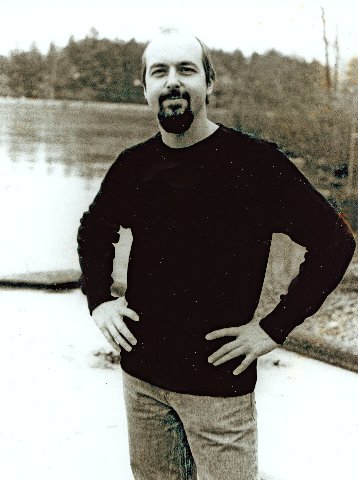

Video Master Bill Viola at 73

Early Work in Boston

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 14, 2024

Bill Viola, the pioneering and renowned video artist has died at 73. The cause was complications of early onset Alzheimer’s disease, said Kira Perov, his wife, studio director and artistic collaborator.

Early on he had a unique relationship with David Ross and eventually Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

After Ross was appointed the first curator of video art at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse in 1971, he hired Viola to be an audiovisual assistant. Viola helped set up exhibitions by the video artists Nam June Paik, Peter Campus and others.

Ross became director of the foundering Institute of Contemporary Art (1982-1991). He left to become director of the Whitney Museum of American art. From there he later organized a global retrospective of Viola’s work.

When Ross took over at the ICA it was low in the water following the administration of Stephen Prokapoff. It was a moment for invention and radical changes. He retained and redirected the staff; most significantly curator, Elisabeth Sussman, who he later took with him to the Whitney.

Looking at the books he concluded that the ICA lacked the resources to mount major exhibitions with catalogues. He devised a radical hit and run program called “Currents.” In essence there were vignettes within the space reflecting the latest tendencies and emerging artists in primarily the New York art world, with some Italians and Russians in the mix.

Initially, they were to occur at whim with quick turnovers. That soon stabilized into several changes, with openings, during a season. There were pamphlets that explained the radical work on view.

During an early interview Ross told me that “I didn’t come here to do video.”

An exception in 1983 was the Viola installation, “Room for St. John of the Cross,” with video and sound that evoke the tiny cell where John, a 16th-century Spanish mystic, wrote ecstatic poetry despite being tortured for months.

The cell was constructed in a gallery with video projections. One bent over to peer inside to grasp the essence of the tortured monk. It was inspiring and simply unlike anything I had encountered.

I pitched it Art News for which at the time I was the Boston correspondent. The piece was given a page. Arguably, it was rare early coverage in a national art publication; notably, for a then unknown, emerging artist.

Later I caught up with Bill and his wife Kira when they were installing a triptych at the Fuller Art Museum in Brockton, Mass. The museum has since changed its name and mandate as the Fuller Craft Museum. I covered the exhibition for the daily Patriot Ledger.

It was an enthusiastic meeting. Kira amusingly told me that she had copied and sent out that piece many times. By then his career had taken off.

He explained the technical changes for the new work. He no longer was reliant on awkward videotape. He was using discs which facilitated easier function for continuous projections.

One panel of the piece entailed a “real time” projection of a California street. He commented on the lawns that required constant use of precious water. It seemed inevitable to him that one day there would be a change to natural and indigenous landscaping.

It became more common to see the work in major museums. There was an escalation as the pieces entailed narratives, often with Old Master references, and costumed actors.

In particular I was struck by "The Greeting" (1995) which evoked the Pontormo Renaissance painting “The Visitation,” depicting a pregnant Mary greeting her pregnant cousin Elizabeth in the Gospel of Luke. It was always exciting to see new and ever more complex works.

In 1989, he received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship — a prize of $245,000 (the equivalent of about $635,000 today). It came at a time when they could use the money though that was less so as his career took off.

On many levels Viola was among the most interesting and innovative artists of his generation.