Czech Republic: Part Three

Slavonice to Slovakia

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 11, 2014

Slavonice is a small town in the southwest of the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, close to the Austrian border. Settled as early as the 13th century, it accumulated wealth due to its favorable location near the trading routes connecting Prague to Vienna. A testimony to the town’s past riches, its historic part is like an open-air museum, with a unique collection of late Gothic and Renaissance houses, mostly from the 16th century, adorned with scratched wall designs known as sgraffito. Walking around the well-preserved graphic decorations offers a treat of predominantly geometric, figural or fantasy designs. The various types of houses feature antique or plain gables, cantilevered floors or fronts with bay windows. Two of the three gates with scratched designs still provide an entry to the town’s historic core.

Beyond the gates we visited Materská Škola Slavonice, a kindergarten and day care center for children ages 2-6. Open from 6 am till 4 pm, the school emphasized environmental awareness, attracting six students from Austria with its reputation. The students were grouped into three sections, each with two open classes where the children chose their own activities. A group of students from different classes put on a program for us. The boys impressed us with their hula hoop skills, following which we had an opportunity to visit the classrooms. The cost to attend this city-supported facility is $10 a day per child plus another dollar for breakfast, lunch and snack.

Artists with newly-found freedom following the Velvet Revolution resettled in houses vacated during Soviet times and opened up studios to teach crafts. We visited the Maríž ceramic workshop, where we each chose a piece to be glazed among many. The white mug I picked turned quickly into a multi-colored one with alternating bands of color, though still in muted tones until after an overnight firing. The next day, a bright shiny mug was packed in a box ready to go home with me. In addition, the gift shop enticed visitors with fine samples of contemporary ceramics. I bought a fantasy coffee pot depicting fish in a sea of color.

Lunch was on our own, encouraging us to walk back to Dum U Ruže, our hotel, where the owners were also the cooks. The grilled carp with a side order of grilled vegetables from the a la carte menu was simply delicious.

After lunch, a hike in the surrounding countryside brought us to camouflaged concrete bunkers from the 2nd World War. Built between 1935 and 1938, the bunkers were meant to guard the Czech border against an invasion by Hitler, who came anyway, but did not meet any resistance, as the area was inhabited mostly by Germans. The fortifications were instead used to prevent Czech citizens from escaping to the West during the ensuing Cold War.

Those curious to see the interior of a bunker, including me, entered through a camouflaged hole. The cramped space consisted of two very small rooms connected by a short corridor. A periscope allowed a view of the outside. Ammunition, guns, and a first-aid kit completed the furnishings. Seven soldiers at a time worked in 24-hour shifts, sleeping outside as needed. A double row of barbed wire, separating Slavonice from Linz, Austria, is still in place.

In the middle of a dense forest nearby are the massive ruins of the Landstein Fortress, built in the 13th century. It was converted into the Rudolec Castle in the 16th century, replete with a dungeon and a treasury guarded by thick bars. The castle ruins stand three stories high.

A home-hosted dinner in a village of 120 people outside Slavonice topped the day’s excursions. The Bochnickov family — he a carpenter, she a gardener running a catering business from home — welcomed us at the door. We watched the wife make apple strudel, which we enjoyed as dessert later on. She rolled out the dough, spreading it with ingredients assembled on the kitchen counter — sliced apples, raisins, poppy seeds, walnuts, cinnamon, and sugar. While the strudel was baking, we toured the garden. Potted herbs and flowers lined the length of the house in front. The back yard was in bloom with flower beds; there was even a house built for insects, crafted out of a variety of wood with different-sized holes to accommodate its inhabitants.

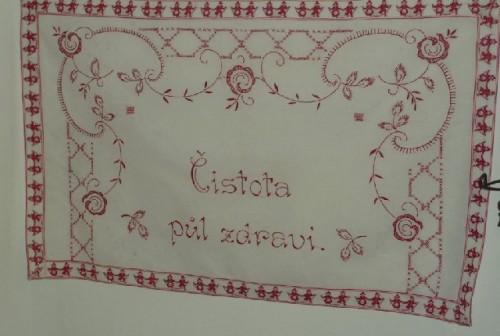

The interior of the country house was equally charming, with hand-embroidered blessings hanging in various areas deemed appropriate, such as the kitchen. The dining room was set to accommodate us around three small tables, each with an elegant arrangement of flowers in the center to match the color of the tablecloth. Dinner consisted of sour soup, made of sauerkraut and cream, followed by pork and bread dumplings. The apple strudel, served warm, topped this hearty meal. Afterwards we each presented a gift brought from home for our hosts. My gift — a Native American dream catcher hung in the bedroom to catch bad dreams and to let good ones pass through — was much appreciated in this household, which cherished folk beliefs. On the way back, the stillness of this charming village reflected in the twilight of the lake begged to be photographed.

On route to Slovakia in the morning, we drove by vast fields of yellow rape flowers as far as the eye could see and stopped in Trebíc, a town home to Jews since the 13th century. The Jewish Quarter, which grew until the late 17th century, became a Jewish ghetto after 1723, when landowner Jan Josef Wallenstein ordered an exchange of houses between townspeople and inhabitants of the Quarter. The entire community disappeared in World War II, when the Jews were taken away to concentration camps.

Today the Jewish Quarter comprises 123 historical buildings, including two synagogues, the town hall, a rabbi’s house, an almshouse, a hospital and two schools. There are narrow alleys between the houses, some of which have been restored and are occupied. Others are in disrepair; some have verandas and balconies dating from the Middle Ages. The Quarter is the only UNESCO-designated Jewish cultural heritage site outside of Israel.

In the village of Lednice, we stopped for lunch at the Grand Moravia Restaurant, which introduced us to Moravian wines. Along with a glass of recommended rosé wine, we were served creamy bean soup with potato roll, roasted chicken with bacon and mushrooms and potatoes on the side — a staple served with most meals — followed by pancake with homemade marmalade for dessert. The menu claimed that the chicken recipe was that of Prince Liechtenstein, dating from 1912.

Famed for its natural beauty with forest and water along with meadows and fields, Lednice was the summer seat of the Liechtenstein family, whose winter residence was in nearby Valtice for almost 700 years until 1945. Through generations they reformed the landscape between the two towns into a cultivated park, making Lednice a showpiece of the power, fame, and abilities of one of the most significant noble families of Central Europe.

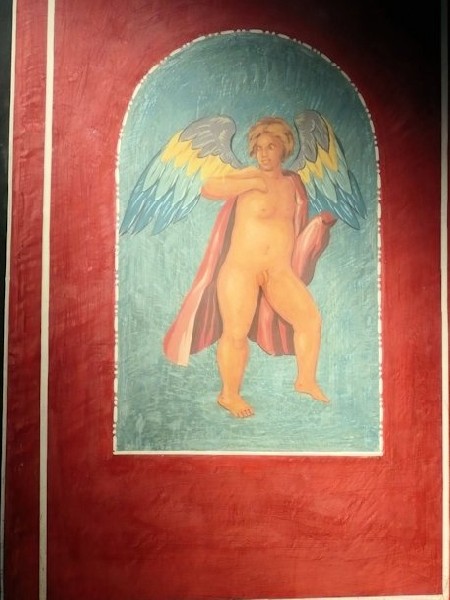

Rebuilt from a one-story country villa in the 17th century, Lednice Château in its present-day incarnation is in the English Tudor Gothic style, linked to an orangery (glass greenhouse). The furnishings of the château are luxurious. Some halls have decorative vaults covered by a network of stucco ribs; others have carved wooden ceilings. Wall coverings, works of art, and carved furniture add to the harmony of the whole. The cut-oak staircase in the library is remarkable.

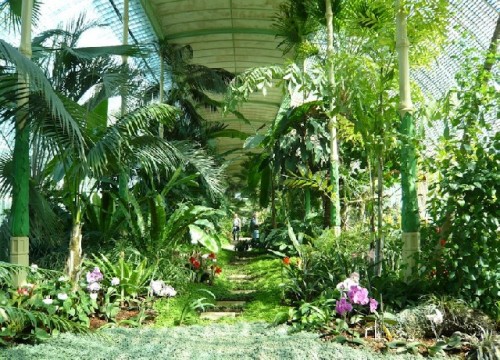

A collection of tropical and subtropical plants and a fish pond are located in the greenhouse, which is supported by an attractive cast-iron skeleton filled with glass sheets. The park in front of the château has significant works of garden art and extends out via alleys to English and French gardens, which are open year-round.

Finally we crossed the border to Slovakia, a country of six million people, and arrived in Bratislava, the capital, set on both sides of the Danube near the Austrian border. At the Devin Hotel, our home for the next two nights, I had a room with a beautiful view of the river. Eager to see what the neighborhood had to offer, we went exploring and were delighted to find that we were near the cultural center of this city of 400,000. Past the Philharmonic Hall, after a couple of blocks we were at the National Theater, facing the compact main square, which was dotted with bronze sculptures both commemorative and whimsical — national author Hviezdoslav with a writer’s plume in hand, a man peeping out of a manhole cover, and a soldier resembling Napoleon leaning on a park bench.

Our first full day in the city was an opportunity to tour the Old Town by foot, and included 14th and 15th-century buildings, such as the neoclassical Archbishop’s Palace and St. Martin’s Cathedral, where several Hungarian Hapsburg kings and queens were crowned. In one of the modern cafes, which also displayed local crafts, I bought a reverse glass painting. Slovakia uses the euro, so the exchange rate to the dollar was not as favorable as it had been in the Czech Republic. Emil treated me to a cup of cappuccino and a piece of delicious carrot cake — much appreciated. Other encounters during this tour included a charming sculpture of Hans Christian Andersen with a child sitting on his shoulder, and vistas of Bratislava Castle high above the city.

In contrast to the vestiges of imperial grandeur, we visited a section of Bratislava on the other side of the river with blocks of housing projects, symbolic of the days of communist-era oppression. A young couple, Ivana and Michal Kondáš, the latter in the computer business, hosted us over coffee and sweets in their compact two-room apartment. At this stage of their lives they seemed to be content with the living arrangements, even with the expected arrival of a child.

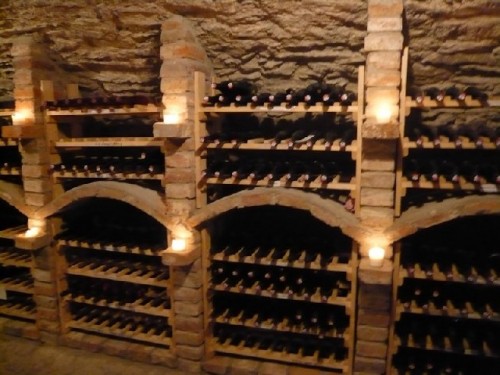

In the evening we journeyed to the village of Modra, on the Small Carpathian wine route, the northernmost part of Europe where grapes are grown. Single-story houses, typical of the villages in the region, clustered around the town square, which featured a single church with a clock tower. Wine-growers owned small lots with a variety of soils. We visited the Ludvik wine restaurant and cellar, a recently restored 17th-century house owned by a man who inherited the property as the oldest son of an old winemaker, according to laws observed since the time of Marie-Thérèse. The husband-and-wife team has won championships and gold medals among wine-makers for the wines they make from their own grapes. The wines are sold only within the country due to the small quantity of production.

Seated around a long table in the cellar, we tasted five kinds of wine, ranging from dry white to rosé and red, accompanied by a selection of Slovakian cheeses. Our memorable dinner began with cream-of-mushroom soup and continued with grilled salmon on a bed of garlic-flavored spinach, with a side dish of roasted potatoes and a mixed green salad. The dessert of sweet homemade noodles with poppy seeds was a new taste!

En route to Hungary the next morning, we stopped at the Roman city of Carnuntum, a one-time Roman army camp set on the shores of the Danube in what is now Austria. The basic architecture of a Roman city quarter has been reconstructed in a unique time frame showing a citizen’s house, a city mansion and public baths from the first half of the 4th century AD. All buildings have been equipped with a Roman radiant heating system using stones placed under the floor; the kitchens are fully functioning and all rooms are furnished. These structures are part of an open-air museum that includes remnants of walls, columns, mosaics, and paths reconstructed from the original stones found during archaeological excavations; valuable objects are exhibited in the Carnuntum Museum.

Home to 50,000 people at its peak, Carnuntum is regaining its ancient glory 1700 years later through admirable dedication.This remarkable detour through Austria set us on our way to Hungary, with much anticipation of further learning and discovery.

(To be continued)