Rock and Roll Man: The Alan Freed Story

Pittsfield's Colonial Theatre Shakes, Rattles and Rolls

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 10, 2019

Rock and Roll Man: The Alan Freed Story

Book by Gary Kupper, Larry Marshak and Rose Caiola

Original music and lyrics by Gary Kupper

Directed by Randal Myler

Choreography by Brian Reeder

Music direction by Dave Keyes

Scenic design, Tom Mackabee; Costumes, Leon Dobkowski; Lighting, Matthew Richards; Sound, Nathan Leigh; Projection and video, Christopher Ash; Wigs, hair and makeup, J. Jared Janas

Cast: Bob Ari (Leo Mintz, Morris Levy), William Lewis Bailey (Dave Cooper, Frankie Lymon, Ensemble), Whitney Bashor (Betty, Alana, Ensemble), Alan Campbell (Alan Freed), Early Clover (Quartet, Ensemble), Richard Crandle (Little Richard), A. J. David (Quartet, Ensemble), John Dewey (Buddy Holly, Pat Boone, Ensemble), Janet Dickenson (Inga, Alan’s Mother, Ensemble), Hayden Hoffman (Lance, Ensemble), Jerome Jackson (Quartet, Nate, Ensemble), Brian Mathis (Judge, Bill Haley, Ensemble), Valisia Lekae (LaVern Baker), Matthew S. Morgan (Chuck Berry, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Ensemble), James Scheider (Jerry Lee Lewis, Dick Clark, Ensemble), Dr. Eric B. Turner (Quartet, Fats Domino, Ensemble), George Wendt (J. Edgar Hoover), Jared Zirilli (Danny of Danny and the Juniors, Ensemble).

Berkshire Theatre Group

The Colonial Theatre

Pittsfield, Massachusetts

June 27 to July 21, 2019

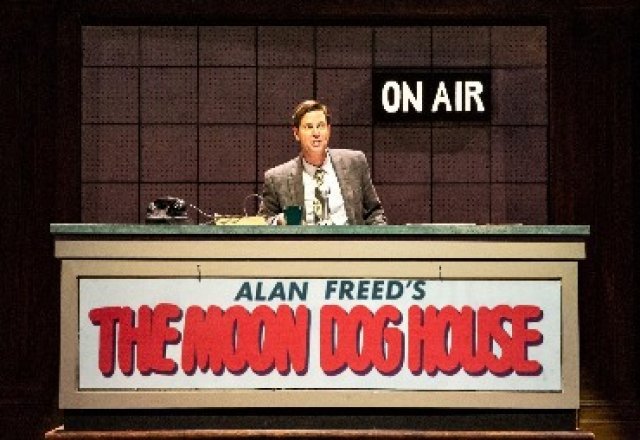

On July 11, 1951, Alan Freed (1921-1965) launched an R&B show on Cleveland’s WJW (850 AM) "The Moondog House." He billed himself as "The King of the Moondoggers". As theme music for the seminal show, which would change forever American pop music, he appropriated the music and persona of the ersatz Viking and New York Street presence Louis T. Hardin.

When a child, playing with dynamite caps, there was an accident that rendered Hardin blind. As a teenager I listened to his poetic, percussive Prestige recordings. It was a thrill to meet him not far from my gig at the cooperative Spectrum Gallery. For a donation he handed out sheets of poems. They were composed in a roach-infested, flea bag hotel not far from Times Square. He told me that mornings were devoted to “canons and coffee.”

In the afternoon he donned layers of blankets/ ponchos and donned his horned Viking helmet. The garb was designed to give him a larger than life presence. He carried a long staff as navigation device and protection.

We collaborated on a performance of his music at the gallery. The event was sold out and Martha Graham sat in the front row. In addition to playing his triangular percussion instrument there was also a string quartet. A dancer from the Alwin Nikolais company performed a solo inspired by the music.

To promote the event I took Moondog to WBAI where he appeared on air with Bob Fass. Not long after the event, in the spring of 1968, I left New York and lost touch with Moondog. He later emerged as a composer with a following primarily in Europe.

When Moondog sued Freed for unauthorized use of his music and name there was a $6,000 settlement. It meant that the DJ had to rebrand his show and famously coined the term Rock and Roll. For this he was inducted into Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when it was launched in 1983. Initially, it housed his ashes which were later moved to a cemetery in Cleveland. He died young from complications of alcoholism.

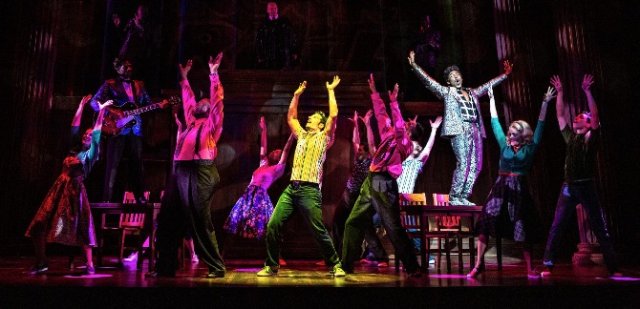

A new musical Rock and Roll Man: The Alan Freed Story is being given a lavish world premiere production by Berkshire Theatre Group. The telling of the birth of rock and roll, with all of that paradigmatic music, would seem to be a sure thing. Based on what we saw at the Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield the production has energy, commitment and potential but requires theatrical triage. It needs revision and tightening to transfer from Berkshires to Broadway.

In a spectrum of stunning performances of now iconic pop tunes there are lots of highlights. On that level it functions like a PBS Oldies show. Clearly, it was nostalgia that inspired an audience of seniors to clap along.

As is too often the case with jukebox musicals there is a weak book connecting the dots of terrific vintage music. A way too long, two act evening bogs down in the details of life and hard times of Alan Freed. As directed by Randal Myler there is an unnervingly bland and apathetic performance by Alan Campbell. Freed is played as a nebbishy, schleppy, lumpen proletariat who pratfalls into changing the world of music. He is a nice guy, straight shooter who later gets mobbed up by Morris Levy (Bob Ari). Freed took kickback to push records that morphed into the payola scandal.

The uncooperative DJ was subpoenaed to appear before a Senate subcommittee in 1959. It was also revealed that Freed glommed co-songwriter credit for songs he plugged on air. That included the iconic “Maybelline” by Chuck Berry. The recording industry routinely screwed musicians out of royalties.

The payola hearings devastated Freed’s career. It brought down the house of cards. Freed had the nation’s highest rating for his Top 40 show on New York’s WINS. That fueled trend setting live rock shows which, with leverage from Levy, went on tour. There was also a contract for several films he starred in.

Targeted in the dream sequence, by none other than J. Edgar Hoover (George Wendt), Freed was prosecuted as a corrupter of youth and instigator of Rock and Roll riots. A particular threat was encouraging his white Moondoggers to love black music.

His TV show ended when a black performer danced with a white girl from the studio audience. The show continued briefly with another host. That morphed into the squeaky clean American Bandstand hosted by a perennial teenager Dick Clark. As another top DJ Clark was also subpoenaed but cooperated. He sold the record label he had plugged on air.

More could have been done with Campbell as Freed. We sense none of his showmanship and charisma. How did he evolve from a square to successful entrepreneur? There is little indication of him as a dangerous force in American popular culture.

Campbell brings a lilting melancholy to original music by Gary Kupper. There is an effort to portray him as a failed but loving family man though three marriages. A compelling relationship to his daughter Alana is nicely conveyed in duets with Whitney Bashor. When things fall apart, however, there is no dimension to his demise. It is indicated by scenes of Freed nipping from a hip flask. We see him tumble from small station to station on the way to an early grave.

The trope and set piece of this production is literally to put his legacy on trial. The prosecutor of the dream sequence, which comes and goes at mishegoss intervals, is J. Edgar Hoover. Familiar as Norm from Cheers it’s odd that George Wendt gets a couple of solo numbers.

Defending the Freed legacy, in the knock out performance of this musical, is Richard Crandle as rock star Little Richard. His tag line is “shut up.” In a glitzy, glittery outfit by Leon Dobkowski his performance is totally over the top. He also sings a sensational “Lucille” and other hits.

Threading through the biography of Freed are some 47 musical interludes combining vintage material and new songs by Kupper with a soupcon of 1950s flavor.

There were many galvanic performances as we stroll down memory lane. So many of the rock songs are now benignly iconic it is hard to imagine how they threatened American values. The performances evoked 45’s that we danced to at house parties and sock hops.

It was a hoot to see them performed. Great balls of fire, yet again, James Scheider ignited a Berkshire audience as Jerry Lee Lewis. Valisia Lekae conveyed the heart and soul of LaVern Baker. Dr. Eric B. Turner knocked the socks off of Fats Domino. An array of R&B quartets were aptly conveyed by Early Clover, A.J. Davis, Jerome Jackson and Eric B. Turner. Matthew S. Morgan, however, fell short of evoking Chuck Berry and Screamin’ J. Hawkins.

Lending much needed insight and gravitas Bob Ari was superb in conveying the two men who most impacted Freed’s career. Leo Mintz ran Record Rendezvous one of Cleveland's largest music stores. He invited Freed to fall by and dig white and black teens grooving on R&B. Mintz bought the DJ’s radio time and they partnered in producing the very first live rock shows. There were more fans than seats resulting in shows being shut down. That was regarded as great PR and led to booking larger venues. Mintz is portrayed as a nice guy who truly loved the music.

That was not the case with Morris Levy. He was the notoriously mobbed-up music entrepreneur and owner of Birdland a legendary New York jazz club. Levy also fronted Roulette Records which recorded Frankie Lyman and the Teenagers (William Louis Bailey). He was a stunning talent-“Why Do Fools Fall in Love”- who overdosed (1942-1968).

In order to get his rock shows produced Freed made a pact with the devil. Much is made of the fact that Levy took “60% and deducted expenses.” But he got shows produced in New York, and on the road. There was a riot in Boston primarily instigated by racist Irish cops. Archbishop Richard J. Cushing (1895-1970), and city censor Dick Sinnott, got rock ‘n’ roll “banned in Boston.” Rock flourished in the 1960s when promoters routinely lined Sinnott’s palm with silver. Covering Dick as a reporter I knew his whimsical wit and Hibernian charm.

In the 1956 film Rock, Rock, Rock, Freed tells the audience that "rock and roll is a river of music which has absorbed many streams: rhythm and blues, jazz, ragtime, cowboy songs, country songs, folk songs. All have contributed greatly to the big beat."

As the first to connect those dots that was his true and enduring legacy.