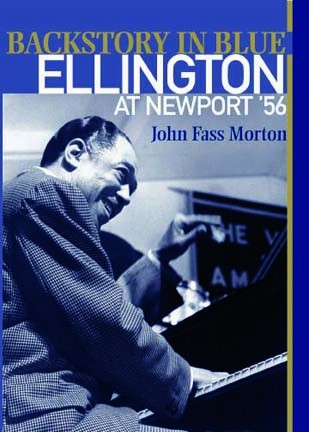

Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport '56

An Absorbing Study by John Fass Morton

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 02, 2008

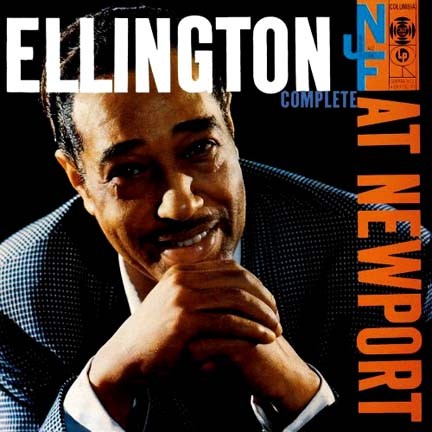

Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport '56

By John Fass Morton

Rutgers University Press. 336 Pages, Illustrated. Release: August, 2008

On July 7, 1956, some 52 years ago, Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington and his Orchestra were the last act of a long Saturday night program at the Newport Jazz Festival. There had been a preview of the Ellington band earlier in the evening followed by other performers. It was near midnight when Duke was back on stage. There was a curfew and the organizer of the Festival, George Wein, told Ellington to keep it short. Already there were folks headed for the exits to avoid traffic.

When Ellington introduced "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue" (1937) one of the more blues based and rocking scores in the vast Ellington book of arrangements, the band began to cook. There was a solo connecting the two compositions which were originally recorded separately on 78 rpm discs. The Cape Verdian born, bop flavored, tenor sax player, Paul Gonsalves, got into a groove. Off stage Joe Jones, the drummer for Count Basie, pounded a rolled up newspaper on his leg inspiring and urging on the rhythm section of drummer, Sam Woodyard, and bass player, Jimmy Woode.

George Avakian had convinced Columbia Records to allow him to record the entire festival for what would prove to be the first live recordings on the relatively new Long Playing Records or LPs. Columbia had subsidized the festival agreeing to pay all of the artist fees in return for the recording rights. But in an executive meeting, shortly before the Festival, Goddard Lieberson, the CEO of Columbia, stated that he intended to cancel the plans for live recording as too risky. He would honor the agreement to pay for the artists but not approve expenses for sending a crew to record the performances. Avakian, who was feuding with Mitch Miller, the middle of the road head of the Pop division to which he answered, argued that it was precisely because of the risk taking that Columbia, a leader in the field, should make this then unprecedented step.

Even Ellington, who had written a new extended work for the occasion, which had not been adequately rehearsed and never performed, was concerned. In booking him to headline the Festival at at time when Ellington's career and reputation had declined George Wein stated emphatically that he wanted fresh material and not a medley of canned hits. This was backed up by Avakian who did not want to record material already released by Columbia. While on the road, Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, his collaborator and arranger, were desperately hoping to finish the new composition facing an ever more demanding deadline. Duke insisted that Avakian book studio time following the Festival so he would have a chance to clean up any glitches on the live recording. Duke anticipated a common practice like the "live" tracks for Crosby, Stills and Nash on the Woodstock album.

Before stepping forward to solo all of Duke's musicians, including Gonsalves, were told to play into the Columbia mike. There was a second mike picking up the performances to be broadcast in Europe over the Voice of America, an important propaganda resource during the era of the Cold War. It was how many musicians in the Communist block were exposed to jazz. The Department of State also organized important tours for American musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Ellingon, and Dizzy Gillespie. Although Dizzy's antics proved controversial during the period of McCarthyism and led to legislation calling for an end of government subsidy of those tours. A Columbia album "Ambassador Satch" was a best seller for Armstrong.

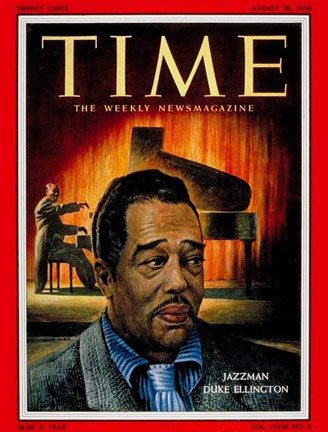

As Gonzales, his eyes closed and feeling the music, got into a groove he ignored instructions and playing off mike was closer to the Voice of America pickup than to the Columbia setup. It was a primitive era for live recordings during a time of mono releases. The word at that time was Hi Fi. The multi track recordings, endless mikes, and mixing boards that are now standard did not exist. Avakian was pushing the envelope but he also freaking out that the Gonsalves solo, which electrified the audience through 26 choruses, would be unsalvageable. There was no way that the spontaneity of that solo could be reproduced in the studio. There was also the matter of all the ambient noise of an audience responding to the energy of the moment. When it was finally released "Ellington at Newport '56" became an all time best selling jazz album. It resurrected Ellington's career and became the hook for a major comeback signified by a cover story for Time Magazine on August 20, 1956. The original Voice of America tapes were later discovered in an archive. They were spliced into the reissue now available on CD.

As a Cape Verdian who often performed at clubs in Rhode Island, New Bedford and Fall River, Gonsalves had many family and friends in the audience. They were in rows just behind the box seats of Newport socialites. One of these society ladies, Elaine Anderson, married to Larry Anderson, a partner in Anderson Little a clothing manufacturer, burst to her feet. Her dancing in the aisles inspired everyone around her and almost prompted a riot. Photographers rushed to record the action and her image, turned away in an ecstatic gesture but concealing her face, appeared on the back of the Columbia album with liner notes by Avakian.

The detailed and informative book by John Fass Morton not only conveys the events of that evening in Newport but also probes deeply in what is aptly described as a Backstory. While there is a focus on the artistic achievement of Duke Ellington, one of the greatest of all jazz composers and artists, we also follow the twists and turns of Paul Gonsalves for whom that was the apogee of a career that stretched on until he and Duke finally died within days of each other in 1974. We also follow the tragic trajectory of the life of the free spirit and Newport muse, Elaine Anderson. Her life began a downward spiral not long after the embarrassment to her husband that led to divorce, other unsuccessful marriages, and eventual destitution. It was a terrible price to pay for one glorious evening that has etched her into the mythology of jazz.

Morton also leads us into the complex events that noted the growth and change of the recording industry and its transition from three minute, 78 RPM discs. Avakian explored the possibilities of putting jazz improvisations on LPs. The new format was primarliy developed for classical music. Initially, he was recruited by Columbia as a fan who reissued hot jazz classics on obscure labels that were out of print.

Columbia had acquired the all black OKEH label with its treasure trove of the Louis Armstrong Hot Five material and all of the sessions by blues legend, Bessie Smith. Avakin organized reissues which became strong sellers for Columbia. His compilations made a lot of money for the label and still do as repackaged CDs. But he butted up against the conservative Mitch Miller (sing along with Mitch) and made an enemy of John Hammond, a fellow Yale alumnus and jazz fan (his mother was a Vanderbilt) who was initially fired and later rehired by Columbia after Avakian quit. Hammond had discovered Count Basie (already signed to Decca in a bad contract). He had been making deals on the side for Basie and other artists. When he returned to Columbia Hammond discovered Aretha Franklin who found success when she left the label and recorded for Atlantic. But Hammond brought first Bob Dylan and then Bruce Springsteen to the Columbia stable. This occurred when Clive Davis brought a new management style to Columbia taking over from Goddard Lieberson. Like Hammond, Davis was later fired because of a scandal.

"The Newport Suite", as the 1956 extended composition came to be known, was the first such effort by Ellington in some time. It is not highly regarded by critics. During the era of 78s Ellington produced multiple sides of a three part, 1943, masterpiece "Black, Brown and Beige." The success of "Newport '56" led to extensions of Ellington's contract and allowed him the freedom to compose and record a number of ambitious compositions of jazz symphonies. The Columbia years gave new life and creativity to a career which was hanging in the balance until that breakout Newport performance.

I was just 15 that summer, with no driver's license or wheels. Even so, it is unlikely that my parents would have allowed me to drive from Gloucester to Newport. But my sister and I had the enormous pleasure of seeing the Duke Ellington Orchestra at Storyville, the Boston nightclub of George Wein. We were taken there by my uncle, James Flynn (Uncle Brother), who to this day remains a great fan of the Duke. There were programs left over from a Newport Jazz Festival at the club and it became one of my treasures particularly with wonderful photography by Avedon.

My first real exposure to jazz had occurred when my hipster uncle, Fred Giuliano, who ran a music store, Freddy's Music Unlimited in Newton Corner, gave me two albums for Christmas in 1954. They were two of producer George Avakian's first Columbia hits: A reissue "The Music of Duke Ellington" and a studio album "Louis Armstrong Plays the Music of W.C Handy." I wore the grooves out of those records.

That night at Storyville was magical. I recall the Black Brown and Beige walls in the Copley Square Hotel. The horn section of Harry Carney, Johnny Hodges, Jimmy Hamilton, and Russel Procope was fascinating. The valve trombone solo of Juan Gonzalez on "Caravan" was riveting as was a Sam Woodyard solo on the Louis Bellson original "Skin Deep." The High C scat of Cat Andreson was breathtaking. The band's brass section used plunger mutes particularly Quentin Butter Jackson covering the famous growls from the Jungle Band solos of Tricky Sam Nanton.. Ray Nance, a trumpet player, also played occasional violin which opened up new dimensions in my thinking about jazz. Every member of Ellington's orchestras through the years, starting with the Jungle Band of the Cotton Club era, was a unique artiist. Ellington and later he and Stayhorn (the composer of the band's signature "Take the A Train") wrote for the unique skills of particular players.

In the basement was Wein's Mahogany Hall a showcase for traditional jazz. Storyville was on Huntington Avenue then on its last legs as a jazz alley. Across the street was The Stables which hosted Boston's Herb Pomeroy Big Band. Further down near Symphony Hall was the Brown Derby across from the old Mechanics Hall. Just the other side of the BSO was the original Opera House where as a kid I saw the last every road performance of the touring company of Oklahoma. They are all gone now to make way for Urban Renewal. Like those after hours clubs in the South End including the legendary Pioneer Club, Estelle's, Slade's, Connelly's Stardust Room, further up in Roxbury. At Connelly's, drummer, Tony Williams, and tenor player, Sam Rivers, were "local musicians" in the house band of Al "Bottoms Up" Tyler which fronted the weekly headliners. For years, it was homecoming when Ellington came to town as many of Duke's players like baritone sax player, Harry Carney, and, alto sax player, Johnny Hodges, were from the Boston/ Cambridge area.

Never shy and with the Irish gift of gab, during intermission, Uncle Brother introduced us to the Duke stating that he was trying to wean me away from rock 'n' roll. The Duke was gracious as always. I stood spellbound as Brother chatted with Duke and then Johnny Hodges.

After that I saw the Duke whenever he was in town. At first, as a teenager, that mean nursing a Shirley Temple at Storyville. I recall Wein playing intermission piano. Brother had chatted with him as they were classmates at Boston University. When Wein closed Storyville, as the Newport Jazz Festival took up more of his time, Duke appeared at the Jazz Workshop and Paul's Mall of Freddy Taylor on Boylston Street. Harry Paul was the long time publicist for Wein and a lot of his Newport organization was rooted in Boston.

During one of those gigs in Taylor's clubs I managed an interview with Ellington. By then, I was the rock and jazz critic for the Boston Herald Traveler. As such I covered and scooped a front page story on the 1971 riot marking the demise of the Newport Jazz Festival. Wein regrouped and formed an international organization. He returned to Newport in 1981.

At the front desk of the Lenox Hotel in Copley Square I asked for the room number for Mr. Ellington as I had an appointment. Approaching the room I heard a loud squabble and a woman yelling "Ok for you Duke." It appeared that her luggage was being thrown into the hall. The door to the suite was open as I knocked and entered. There was nobody around as I called out softly "Duke, Duke." Eventually, from an adjoining room the maestro appeared in a silk dressing gown. He was wearing a knotted silk stocking over his head. The doo rag kept his konk or process in place.

With an autocratic flourish Duke settled onto a couch as I introduced myself. "People can be so rude" he remarked by way of explanation of the encounter. I was having an audience with jazz royalty. As always Duke was regal when asked about his current projects. "I am writing about my favorite topic" he answered. I asked what that might be. "Me" was the simple response. That was around 1970 and his autobiography "Music Is My Mistress" was published in 1973.

Glancing at the writing in my reporter's notebook Duke asked if I "had enough." Then announced that "I have to lay my head on some feathers."

That night was typical of what one experienced late in his career. Ellington performed right up until the end when he died at 75 on May 24, 1974. Often the band members were late, as they were on the night of the first set at Newport in 1956. Several of the band members were drinking at a local hangout but they arrived for the midnight set. Now doubt with a good buzz that fueled the now legendary funk. Often Ray Nance strolled in having copped while Gonsalves nodded off. During a Boston gig I recall him slumping over and falling over a table next to the bandstand. Never breaking composure Duke deadpanned "He has such a marvelous sense of humor."

One sensed that Ellington presided over an unruly crew but carried them out of intense loyalty to an assembly of remarkable artists. It was in stark contrast to watching James Brown fine his players on stage when they dropped a note. Or the kind of discipline we saw Buddy Rich impose on his band. Duke was clearly the boss but had a light grip on the reins of gifted artists.

Although they were high or messed up he called their number. When Gonsales nodded off, as he did that night, with a great flourish Duke would say "Here to reprieve his great Newport Jazz Triumph is Paul Gonsalves in Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue." After searching through the book the band would settle in as Gonsalves would struggle through the solo section. Often the result was rather poignant and sad. It made you wonder why Duke carried those wasted players.

But it was part of the unfathomable mystique of Ellington and his remarkable Orchestra. Sure there were uninspired nights particularly for a band that was constantly touring. Duke thrived on the road and in the studio. It was remarkable that he was able to endure when first Bop and then Rock ended the Big Bands. Only he and Basie survived intact although there were tough years. I hung out with Stan Kenton when he tried to bounce back after being canned by Capital Records when they signed the Beatles. Kenton formed his own label Creative World to reissue the Capitol material as well as put out new work. Most major labels dropped their jazz artists. Although Columbia hung in with Miles Davis particularly after his landmark fusion album "Bitches Brew" in 1969. It was Columbia's Sal Ingeme that hooked me up with Miles when that album was released. But that's another story.

Going back to that first night at Storyville I always loved the Big Bands. And none more so than the Duke. The wonderful book by John Fass Morton brought it all back and filled in so much of that remarkable Backstory. Thanks man. What a treat.