The Lion in Winter Roars in Stockbridge

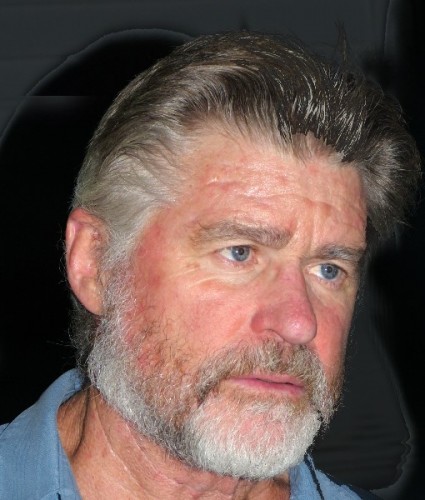

Treat Williams and Jayne Atkinson Star for BTG

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 01, 2013

The Lion in Winter

By James Goldman

Directed by Robert Moss

Scenic Design, Brett J. Banakis; Costumes, David Murin; Lighting, Solomon Weisbard; Composer/ Sound, Scott Killian; Casting, Alan Filderman; Stage Manager, Stephen Horton

Cast: Jayne Atkinson (Eleanor of Aquitaine), Treat Williams (Henry II, King of England), Tara Franklin (Alais Capet), Aaron Costa Ganis (Richard), Karl Gregory (John), Tommy Schrider (Geoffrey), Matthew Stucky (Philip Capet, King of France).

Berkshire Theatre Group

The Fitzpatrick Main Stage

83 East Main Street

Stockbridge, Mass.

June 25 to July 13, 2013

During the heat of a family squabble, set during Christmas at the Palace of Chinon, France, Eleanor of Aquitaine (Jayne Atkinson) the estranged and imprisoned wife of Henry II, King of England (Treat Williams) bellows “It’s 1183 and we’re barbarians.”

That’s The Lion in Winter in a nut shell.

The biting irony is hilarious and results in a roaring burst of laughter from the audience.

Atkinson has all the best lines and may be the only truly engaging and sympathetic character in this period piece by James Goldman which hovers precariously between docudrama, faction and situation comedy.

The historical Henry II (1133-1189) was indeed a larger than life individual. Drawing on a passion for history as a dramatist Goldman focuses on his known traits; a piercing stare, bullying, bursts of temper and, on occasion, sullen refusal to speak. According to chroniclers he was good-looking, red-haired, freckled, with a large head and short, stocky body. When not on the field of battle he enjoyed hunting.

To describe him as King of England is misleading. Better to say a piece of England and the better half of France. From the Plantagenet dynasty he held the titles of Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Count of Nantes, King of England (1154–89) and Lord of Ireland. At various times, he also controlled Wales, Scotland and Brittany.

Charlemagne (742 -814), as Einhard described him, could not read or write but in addition to his native Frankish spoke several languages. Similarly, Henry understood a number of languages. He spoke French and Latin but apparently not English. Until Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343 – 1400) the language of English was a mishmash which was further refined by William Shakespeare (1564-1616).

Given the state of language during this period Goldman inflects no medievalisms and has the characters speak and think in contemporary argot.

Henry II was England’s last absolute monarch.

The Henry we see in Goldman’s play is a literary fantasy which makes for passable theatre but awkward history. Most Americans know little or nothing of British history of this period and its Plantagenets. We see rulers through the plays of Shakespeare or follow today’s royals through the gossip columns.

In every aspect Henry was a remarkable man of his times. Arguably, the three sons we find jockeying to succeed him in this play- Richard (Aaron Costa Ganis), John (Karl Gregory), and Geoffrey (Tommy Schrider) pale by comparison to their bellowing, despotic father.

The Lion in Winter opened to mixed reviews on Broadway in 1966 at the Ambassador Theatre. It was directed by Noel Willman, and starred Robert Preston as Henry, Rosemary Harris as Eleanor, James Rado as Richard, and Christopher Walken as Philip. Harris won a Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play.

The 1968 film won three Academy Awards. Katherine Hepburn tied with Barbara Streisand as best actress for Funny Girl. Peter O’Toole played Henry with Anthony Hopkins in his first film role as Richard. O’Toole also played Henry in the earlier 1964 film Becket by Jean Anouilh with Richard Burton as the king’s former friend/ lover Chancellor and then enemy as Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Anouilh play surpasses Goldman’s in providing a better understanding of Henry and his role in medieval history. Like the later Henry VIII he chafed against the constraints of the Roman Catholic Church and its Pope. By installing Becket as leader of the English church he hoped to influence, modify and weaken its authority. Becket the rake and companion of the prince who became king reformed when, with no ecclesiastical training, assumed an appointed position as leader of the church.

By popular account Henry II said “"Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" More accurately contemporary biographer Edward Grim, writing in Latin, quoted "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?" Becket, who resisted arrest, was slaughtered by four knights. In death he became a martyr. Henry suffered penance and obeyed the church which Henry VIII later challenged.

If Henry was paradigmatically medieval Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122 or 1124- 1204), who was almost a decade older than her second husband, was even more remarkable. As the heiress to the vast region of Aquitaine she was the richest and most powerful woman in Europe.

Women were little more than breeders of heirs and pawns on the chessboard of alliances, and acquisitions of territory. Eleanor brought much to the bargaining table first as wife of Louis VII of France from 1137 to 1152 bearing two daughters resulting in an annulment. To the displeasure of Louis she married his mortal enemy Henry and bore him eight children, five sons and three daughters. William died as an infant. Young Henry, the next in line, was appointed king but with no land or money. This led to his uprising and early death.

In a line that rings false Henry compares himself to King Lear. There was a legendary Leir of Britain, a mythological pre-Roman Celtic king. Henry speaks of not wanting to turn over his land and power. But it is Goldmnan obliquely and improbably referencing Shakespeare who lived much later.

Lear is a handy shortcut for the audience but a complete stretch of reality.

The dilemma for Henry is to pass on the whole of his property to a single heir. John appears to be favored. Or to settle it in large portions among them. Like the mythical Lear he made his son, Young Henry, King but with no real power or authority.

Remarkably, Eleanor lived to be 82 while Henry survived to the then ripe age of 56.

During the family holiday of 1183 Henry was still robust and randy at 50. We find him during the first act, in a truly magnificent Gothic castle designed by Brett J. Banakis, in bed with his mistress the teenaged Alais Capet (Tara Franklin). She was the sister of the young French king Philip Capet (Matthew Stucky) who is also there for the occasion. The maiden has been engaged in childhood to Richard and raised by Eleanor.

In a lively exchange Henry boasts of his sexual prowess with mistresses, whores and boys. Eleanor is more discreet but also has taken pleasure aside from the marital bed. It is implied that she slept with Henry's father and perhaps his beloved Becket. We also learn that Richard seduced the young King Philip in a love that was not reciprocated.

Bisexuality appears to have been rampant during the Middle Ages. Particularly among royals and priests.

For the family holiday Eleanor has been released from a castle in England. She was confined there as punishment for siding with her sons against Henry in the Great Revolt of 1173-74.

Alais is just the latest of several mistresses. Because the sons have revolted against him he aspires to annul the marriage to Eleanor and start a new family with Alais. After Christmas he is determined to leave abruptly for Rome.

When this is revealed Eleanor has some of the best lines in the play mocking a dottering old man raising an infant. The new heir, upon his death (just six years later from a bleeding ulcer) would surely be killed by Henry’s conspiring sons.

As we see the three princes jockeying for power they are wretched and unattractive human beings. They behave like many families when there is sizable inheritance. We agree with Katherine when she humorously states that she doesn’t like their children. It is interesting that their daughters are never mentioned. How medieval.

In some ways the most interesting of the three surviving heirs is Geoffrey. Compared to the sniveling, pimple faced, cowardly and smelly John, or the swaggering bellicose Richard, Geoffrey is clever, Machiavellian and the brains of the family. Henry ignores him.

Matthew Stucky plays him deliciously. Often proclaiming in essence "Hey pop, look at me, look at me."

John and Richard, both kings, loom large in British history.

Richard “The Lionhearted,” primarily a warrior, after his coronation, joined the Third Crusade. He was captured and held for ransom. As ruler in his absence the horrible John (of Robin Hood fame) could care less about releasing his brother.

The taxes and tyranny of John resulted in Magna Carta in 1215. The evil king, one of the most reviled of British history, died a year later.

Magna Carta established English Common Law. It created Parliament which restricted the absolute power of a king as a constitutional monarchy. We look to it as the foundation of our system of law and government.

Have you ever read it?

Consider item 10. “If one who has borrowed from the Jews any sum, great or small, die before that loan be repaid, the debt shall not bear interest while the heir is under age, of whomsoever he may hold; and if the debt fall into our hands, we will not take anything except the principal sum contained in the bond.”

Or provision 11. “And if anyone die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and pay nothing of that debt; and if any children of the deceased are left under age, necessaries shall be provided for them in keeping with the holding of the deceased; and out of the residue the debt shall be paid, reserving, however, service due to feudal lords; in like manner let it be done touching debts due to others than Jews.”

Perhaps these passages of Common Law shed light on Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice as sui generis.

We recount some of the facts as an attempt better to understand the history, culture and literature from which Goldman has written an ersatz historical pastiche.

This makes for, here is the key word, entertaining, theatre.

It is easy to understand why mid career actors and actresses drool to sink their chops into the meaty roles of the swaggering Henry and conniving Katherine. Here the superb tandem of Williams and Atkinson soars as he bellows while she cunningly schemes and outwits him.

As an absolute monarch Henry has it all but is on the brink of losing everything. Eleanor, while not during the time frame of the play, later triumphs and prevails.

When Henry died in 1189 she was released from prison. In the absence of Richard the Crusader she ruled the Aquitaine. She died a scant two years before her son John.

What a woman.

Goldman might well have titled his play Eleanor of Aquitaine.

In Stockbridge Atkinson plays her brilliantly getting the loudest laughs of the well received evening.

While the play rightly draws its strength from the royal couple the sons and Alais have wonderful theatrical opportunities. Overall it was a superb supporting cast. We suitably loved and hated them all.

This is a wonderful production of an enduring and popular play.

My concerns lie with Goldman playing fast and loose with complex history. The audience emerges from the theatre assuming they have learned something about British history. Not true. Rather they have absorbed gobs of misinformation. Particularly the absurd notion that these Plantagenets are just like us or any dysfunctional family.

That plays to the vulgarian conceit of the undereducated seeing history through our own eyes and life experience. These people were not like us. They were medieval. Other than sets and costumes none of the language and manners in the play gave a hint of medieval life.

It was squalid, mean, disease ridden, and generally horrible. The devout believed that the Kingdom of Heaven was not of this world. You suffered through life, with all of its aches and pains, on the promise of eternal bliss in the hereafter.

If you believe that then you would have loved the Middle Ages.

During that miserable time the poor starved while the rich sucumbed to gout.

Perhaps given the general misery it was not so bad to trust in the Lord and die young.

Most likely the historical Lion in Winter was toothless, lame, impotent, gouty and blind as a bat.