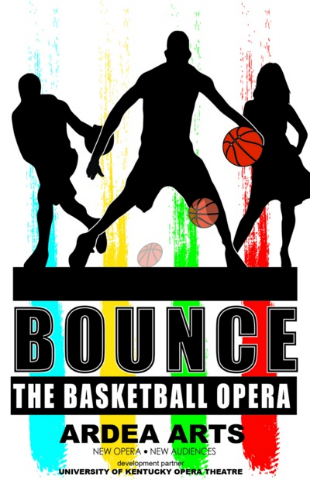

Bounce, the Basketball Opera

Live Basketball, Live Singers, Infectious Drama

By: Susan Hall - Jun 26, 2016

How does a producer or composer select the subject of an opera?

Verdi wanted to do Shakespeare, and some think his Otello is better than the Bard’s. He wrote Aida because he got a fat commission from Cairo's Khedivial Opera House.

Wagner often turned to myth. Both Mozart and Rossini used the fabulous Beaumarchais, himself a figure in John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles.

John Adams has taken momentous historical events and helped our understanding of them as he colors with a musical brush. Tobias Picker was inspired by a great American novel. Philip Glass has textured characters like Einstein and Ghandi.

For whatever reason, these operas seldom draw crowds in America.

Sometimes, when Shakespeare is played for his intended sexual and blood violence, as in Macbeth, young people respond.

Yet there is a problem entering an opera house, where, although dress is no longer mandatory, moving chandeliers and housing 4000 seats discomfort. Intimate opera fares better in the age of Facebook and Twitter. At least Glass wrote that the audience should be able to move freely in and out of the theatre during performances of Einstein on the Beach.

Occasionally opera is taken to the parks, but usually it’s singers performing unattached arias. Opera is not presented in even semi-staged concert productions.

What would happen if you really took opera to the people, in their place with their subject matter? One proposition is made by the gifted director and choreographer Grete Barrett Holby.

Why not do a basketball opera on a basketball court? Why not mix a much loved sport that urban and suburban kids alike play with a story, recitative and arias? It is a tall order and the first public workshop production of Bounce is being held on a basketball court in Paedergat Park, East Flatbush, New York.

Some audience members are seated on a slight grade on the south side of the court. Dressing rooms are in a tent behind the opposite side. Kids whip by on bikes and scooters. Parents crane their necks from the swing section of the playground on a rise to the west.

This is a people’s opera in a people’s park. Holby is charming as she thanks the natives for their gracious acceptance of her usurpation of their territory. No one objects as uniformed players hover outside the court, waiting for the game and the opera to begin. They will begin at once, together.

Dramatic bouncing of the balls and dribbles sound like rhythmic drumbeats. A small orchestra is tucked into the northwest corner of the parking area. Everett McCorvery of the University of Kentucky conducts on the center line. The home of the Wildcats first developed this project. The University also has a distinguished opera department

Holby sits beside the conductor, watching her work, sometimes pleased, sometimes self-critical. She also functions as the prompter’s box. It is no mean feat to coordinate all these elements.

We spoke to her by phone as she worked in a recording studio last week. She was finishing up tracks. When a group of players huddles with the coach, their muffled voices in conversation are heard over loud speakers. Canned voices mix with live ones. The libretto is by poet and author Charles L. Prince.

Prince grew up in Los Angeles and has always been an avid basketball fan. He did sprints until he ached, hoping to strengthen his legs so he could dunk. He claims he can still hit a triple from way out.

The poetry of the game and its lessons are beautifully expressed in the libretto. Sometimes they are cruder and rougher when they’re rapped. Prince captures the language of the game and seamlessly interweaves it with charges down the court and slam dunks. Composers Glen Roven, Tomas Donker, and Ansolo are credited. Hip hop is mixed with contemporary classical in arias and duets.

The story itself is perhaps packed too full. We have references to Greek drama and team names like the Spartans and Trojans. Teen angst in feckless girlfriends, and the conventional emergence of the beautiful tutor who without glasses is suddenly desirable. A playground shooting that kills a young boy gives an opportunity for a communal gathering and repentance. Bad guy versus good guy are on the same team. There is a mysterious Cassandra-like figure who floats in now and then and lofts lovely notes. But this is a work in progress, and surely it will be pared down and shaped as its workshops continue.

Mostly we have the game. Daivd Halberstam, asked why he, a gifted political writer, wrote on sports, said, “This is where it all begins.” And it does.

Mixing actual played games, with a live announcer responding to lightning quick speed and zig-zags, and putting up points in the moment, gives immediacy to the production.

What a great idea is unfolding in East Flatbush.