Poland: Part One

Krakow and Auschwitz

By: Zeren Earls - Jun 26, 2015

My chance encounter with Vita Seputye, an attractive Lithuanian woman, in Prague a year ago led me to sign up for Overseas Adventure Travel’s The Baltic Capitals and St. Petersburg itinerary, which also offered a pre-trip to Poland. A trip leader for the tour, Vita shared her passion for this part of Europe, which was unknown to me.

Bookending the trip with my biannual visit to Turkey, I flew to Krakow from Istanbul to join a group of eight Americans, who had also signed up for the pre-trip. Since I arrived in Krakow after dark, I looked forward to the city tour in the morning. Adjusting my watch by one hour from Istanbul time, I dropped off to sleep in my comfortable room at the Ostoya Palace hotel.

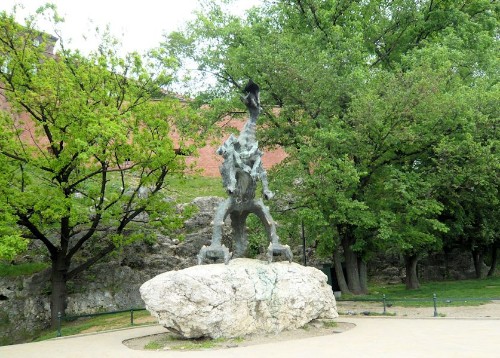

The city tour began on Wawel Hill, a limestone elevation within the marshy surroundings of the Vistula River and home to an ancient castle dating from the 9th century. A densely built-up ducal seat was located at the castle, which became the scene of royal funerals and coronations until the 17th century, when the state capital was moved to Warsaw. A bronze effigy of a terrifying cave-dwelling dragon, vanquished by the legendary founder of the city, Prince Krak, stands in front of the cave at the foot of the hill.

The main entrance to Wawel is the Gate of Crests, adorned with the crests of lands once belonging to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Defense walls with watchtowers encircle the compound of the Royal Castle, the Wawel Cathedral and the vicarage. The bones of post-glacial animals hang over the cathedral entrance. Visible in the square in front of the cathedral are the surviving foundations of Wawel’s medieval structures. The castle’s rectangular courtyard is surrounded by two-story arcaded galleries, which at the time of our visit exhibited the Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (ca 1490). The artist’s only work in Poland and a rarity worldwide, the painting belongs to Krakow’s National Museum.

At the base of Wawel Hill is Krakow’s elite quarter, comprising grand mansions and churches. Riding through the streets on a golf cart — a popular way of sight-seeing in town — was a treat to the eye. Krakow, a city of about 600,000 people, managed to escape major damage during World War II; the Old Town (Stare Miastro) displays seven centuries of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque architecture, ringed by parkland known as the Planty. St. Mary’s Basilica, the Town Hall and numerous cafés line an enormous medieval Market Square, where horse-and-carriage rides, people, and pigeons enhance the local color. The Basilica’s large altar is open daily at noon for viewing scenes from the lives of Mary and Jesus Christ, which attracts large crowds.

During our free lunch hour, I accompanied Vita to the canteen at the university — established in 1364 — where a hearty soup and salad cost me about two dollars at the exchange rate of three Polish zloty to the dollar. Taking advantage of the free afternoon, I returned to the Market Square, at the center of which is the Drapers’ Hall (Sukiennice), a Renaissance structure built around two rows of market stalls forming an inner alley. The stalls are jammed full of goods, from amber to leather and souvenirs.

As we were always on the lookout for something different, Vita informed us that there were voice and piano recitals to be held at the Krakow Music Academy later that afternoon. Six of us welcomed the opportunity and were thrilled to hear a graduating class of voice students, who sang arias by Schubert, Debussy, Schumann, Berg, and Britten with great competence and flair. At the completion of each recital, we took turns giving the students a red rose — a token wish for a bright future.

For dinner we opted for a piroji restaurant to try the special Polish dumplings, which come with a choice of fillings, such as meat, mushroom, or spinach. To drink, I ordered another local specialty — a cup of warm beet juice, mildly flavored with garlic, which was delicious. Following this tasty and affordable meal, we joined others for people-watching over ice cream at an outdoor café on the Market Square.

Crossing the bridge over the Vistula the next morning, we arrived in Podgorze on the right bank of the river. Formerly a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, the center plaza now displays a haunting scene of empty chairs, installed by the municipality in 2005 as a reminder of the belongings left here by its residents, who never returned. From here we drove on to Kazimierz, a town settled by Jews in 1495 on orders from King John Olbracht, who created a ghetto surrounded by a wall.

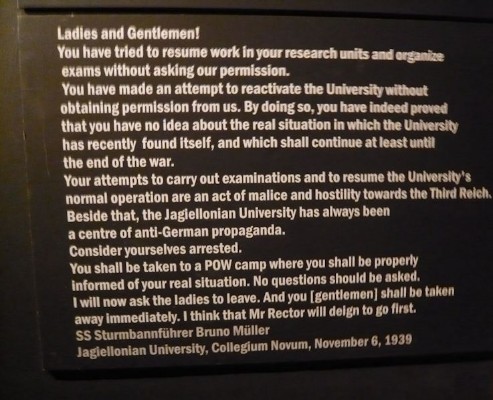

A heart-wrenching experience was a visit to Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory, which is now a branch of the Historical Museum of Krakow, with a permanent exhibition called Krakow under Nazi Occupation 1939-1945. Opened in 2010, the exhibition presents the successive stages of the wartime history of Krakow’s residents, Oscar Schindler’s former German enamel factory, and the prisoners at the Plaszow Concentration Camp who he managed to save by employing them. The war narrative carries on through three floors with original objects, photographs, documents, special reconstructions, and multimedia presentations. These ended with a huge portrait of Joseph Stalin, made in likeness to those set up in the Main Market Square by the Red Army when it entered Krakow on 18 January 1945, the same date stamped on the admission ticket to the museum. Finally, the door of a freight car symbolizes the post-war returns of exiles and inmates to Krakow, while serving as a harbinger of the transports sent to Siberia by the Communist authorities.

On the way to a local restaurant, we stopped by the Remuh Synagogue, adjacent to Poland’s oldest Jewish cemetery, in which Jews were buried as of the mid-16th century. Uniquely symbolic Renaissance-style tombstones and a Wailing Wall have survived. A comforting ambience and a delicious lunch at a neighborhood restaurant eased the stress of the morning’s excursion. Following a tomato and mozzarella appetizer, we had salmon with beet sauce, roasted potatoes and a salad of carrot, cabbage, and cucumber, followed by ice cream.

An optional tour to the Bochnia Salt Mine, 12 miles east of Krakow, revealed its economic impact, which drove the urban and industrial development of the region. An excavating plant dating back to 1248, the salt mine is today a state-of-the-art facility. We descended to a depth of 230 meters in an industrial elevator, and then rode an underground railway. As we walked through winding corridors, multi-media presentations with animated figures informed us about salt mining and the hardships of miners. Our path led to the St. Kinga Chapel, carved from rock salt and dating from 1754. Reaching a 140-meter slide connecting the two levels of the mine, we had a choice between using the world’s longest slide and descending 307 steps to the lower level; I opted for the latter. We completed our tour of the underground town arriving in an enormous space which housed treatment and restorative salt chambers, along with a basketball and a football court doubling as a function room for banquets and events.

The Bochnia tour included dinner at a local restaurant, where this time piroji was served in beet juice as a soup. The many ways Poles include beets in their diet — in soup, sauces, drinks, or salads or as a side dish, all served hot or cold — inspired me to buy beets more often back home. Following our delicious meal, we returned to Krakow to get ready for our morning departure to Warsaw.

Before heading north to Warsaw, we drove west to Oswiecim (Auschwitz), the town of the infamous concentration camp. Of Europe’s 15 million Jews, 3.5 million lived in Poland, where they had been encouraged to live by the king because of their skills as good tradesmen. Jews from European countries occupied by or allied with Germany were also deported here.

Advance registration is required to visit the Auschwitz and Birkenau camps, which are two miles apart. As tour groups arrive, guides are assigned to lead the visitors, many of whom are young. The emotional journey weighed down on us as we listened to stories about people marching past an officer who sorted them by age and stamina for eligibility to work by a show of his thumb. A downward motion deceived the prisoners, including children, into “taking a shower,” leaving their clothes behind as they walked into the gas chamber. The bodies were cremated afterwards and the ashes used as fertilizer. Personal belongings such as glasses, hair brushes, shoes, etc. were sorted into heaps for recycling. At Birkenau we viewed small brick bunkers where prisoners had slept on hay or were forced to sleep standing in groups of four.

Between 1940 and 1945, 1,100,000 people died in Auschwitz; 90% of them were Jews. Emotionally drained, yet thankful for the opportunity to have learned on site about one of the darkest periods in history, we headed to the shrine in Czestochowa, a pilgrimage site on the way to Warsaw.

(To be continued)