Dennis Krausnick Masterful as King Lear

Stunning Production by Shakespeare & Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 24, 2012

King Lear

By William Shakespeare (written between 1603 and 1606, later revised)

Directed by Rebecca Holderness

Set Design, Sandra Goldmark; Costume Design, Govane Lohbauer; Lighting Design, Matthew E. Adelson; Composer/ Sound Design, Peter Bayne; Fight Choreographer, Michael F. Toomey; Voice and Text Coach, Elizabeth Ingram; Production Stage Manager, Hope Rose Kelly

Cast: Thomas Brazzle (Duke of Burgundy/ Ensemble), Caroline Calkins, (Maid/ Ensemble), Kevin G. Coleman (The Fool), Jonathan Croy (Earl of Gloucester), Timothy Douglas (Oswald, Steward to Goneril), Jonathan Epstein (Earl of Kent), Kelly Galvin (Cordelia), Dennis Krausnick (King Lear), Zoe Laiz (Herald/ Ensemble), Peter Macklin (Edmund, bastard son of Gloucester), Corinna May (Goneril), James Read (Duke of Albany), Eric Sirakian (Kent’s Gentleman, Ensemble), Brendan Sokler (Captain/ Ensemble), Enrico Spada (King of France/ Ensemble), Alex Stewart (Cornwall’s Servant/ Ensemble), Bill Watson (Duke of Cornwall), Ryan Winkles (Edgar), Kristin Wold (Regan)

Shakespeare & Company

Founder’s Theatre

June 16 to August 19

Running Time: Approximately three hours with one intermission

In the career of a Shakespearian actor there are well defined challenges and milestones. An adolescent or young actor first comes to attention in Romeo and Juliet. By mid-career there are the monumental roles of Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, Shylock and Richard III among others. It takes a lifetime of experience to reach an apogee in that greatest of all summits King Lear.

The actor must be mature enough to convey the age of Lear yet sufficiently fit to do so with requisite energy.

Last night at Shakespeare & Company, in a deeply, resonant, nuanced and complex performance, a 35-year-long founder of the Berkshire based company, Dennis Krausnick, was magnificently triumphant as King Lear.

The dramatic arc of the character is daunting.

We first encounter the elderly king fully in charge of self, family and kingdom. He conveys misguided trust in the love of three daughters- Goneril (Corinna May), Regan (Kristin Wold), and the youngest, his greatest joy, Cordelia (Kelly Galvin).

His rather foolish (there’s that key word) plan is to divide his kingdom in order of their proclamations of love and devotion. Then “retired,” with an entourage of a hundred courtiers, Lear will live out his remaining years visiting their realms.

The first dramatic demand on Krausnick is a mutation from joy in the falsely sumptuous utterances of Goneril and Regan, rewarded accordingly, then darkening into rage while reacting to the sincere, but plain and unembroidered, honest response of Cordelia.

For all of the power and authority of Lear his tragic flaw, on which hinges this drama, is an inability to hear the truth. Before Shakespeare wrote King Lear Machiavelli advised in The Prince (published in 1532) that “flatterers should be shunned.”

In their subsequent actions, stripping Lear of all of his ceded power and authority, perhaps the evil Goneril and Regan are correct in their observation that their father is a dottering, senile old man losing his grip. Lear has naively entrusted himself to their care through power of attorney. In one of his last “rational” acts as king he signed his life over to them. By releasing control of the purse strings he has no leverage over their contempt and ingratitude.

For Lear, what we would today describe as a 'living will' proves to be a death sentence.

Reaching the arc of the role Lear must respond in rage to their insults. Like Oedipus plucking out his eyes, Lear condemns himself as a wretch in the wilderness. There, accompanied by his Fool, Lear is tended to by Kent (Jonathan Epstein) who he “blindly” banished. Kent returns in disguise to look after the king he remains loyal to.

The great conundrum presented by Shakespeare, and a daunting challenge for actors, is the question of who is the real fool, Lear, or his Fool (Kevin G. Coleman)? Through the device of wit and humor the Fool is the only one empowered to speak the truth. Because this wisdom is conveyed by The Fool, Lear, arguably more of an arrogant idiot than fool, opts not to listen.

Significantly, Lear reached the decision to divest himself of power without benefit of a privy council. A king is only as wise as his advisors. Since he acted alone in such a poor decision perhaps he was indeed unfit to rule and ready for “assisted living.”

As the king, self exiled to the wilderness, descends into madness (conveyed perfectly by Krausnick) there should be a transference. It evokes one of those classic Laurel and Hardy moments of “Another fine mess you have gotten us into.” The Fool should convey misgivings about how the heck did I end up in the wilderness. But I didn’t quite grasp that nuance from Coleman’s Fool who was better at conveying whimsy than imparting ironic wisdom.

The power of King Lear is what it instructs us about elders with assets and heirs who scheme for the greatest shares of inheritances. Particularly when elderly and infirm, parents are vulnerable to false proclamations of love, ersatz support, and flattery. As Astrid commented to me it’s why Queen Elizabeth is not abandoning the throne. She still controls the power as Prince Charles is an aging senior citizen waiting for his mom to croak.

It is not surprising that Shakespeare & Company would mount such a stunning production of King Lear. Its star is an in house actor as are many of the leading characters. Of these we particularly note the fine work of Epstein making the most of the minor role of Kent. Jonathan Croy was a suitably inept and then blinded Earl of Gloucester. Corinna Kay was rightly arch and chilling as the eldest daughter Goneril as was Kristin Wold as Regan. The youngest, Cordelia, Kelly Galvin, never quite reached the emotional and dramatic benchmark of the other sisters.

Much has been made in the pre-publicity of the decision of director Rebecca Holderness to set the action during the era of the Tsars in the Russia of 1906. Other than the gorgeous and inventive costume designs of Govane Lohbauer there was scant evidence of that time and place. The setting of Shakespeare’s Lear is not really Elizabethan. He borrowed the character of Lear from pre-British Celtic history. Lear is a universal tale not confined to a specific time and place.

Holderness has given us a fluid, articulate, fast paced production. She makes optimal use of the thrust stage and aisles leading to it. Yet again she is working with a bare pipe set with a few cloth hangings (designed with minimalism and expedience by Sandra Goldmark). But she got terrific use of the superb lighting of Matthew E. Adelson, and sound by the composer Peter Bayne. With an economy of means we had the impression of shifts from court to heath.

There was a curious device of a ladder descending into a pit. Like sailors in the rigging of a tall ship cast members clambered up and down this structure. It was an odd touch.

In addition to the evil sisters Regan and Goneril the play has another bona fide villain in Edmund (Peter Macklin) the bastard son of Gloucester. Driven by different motives he compares to that better known villain Iago in Othello. In a parallel story of inheritance Edmund plots to discredit his brother Edgar (Ryan Winkles). Like Lear, Gloucester fails to see the truth and is metaphorically (again like Oedipus) blinded and cast out.

Macklin is not a regular member of the company and has been miscast in a secondary but pivotal role. His lines were not clearly enuncatiated and there were no well defined shifts marking his deceptions and maniuplations of the other characters. He just seemed out of sync with the production. We never got a firm fix on who and what he is.

Having managed to oust Edgar the scheming Edmund aspires to greater power by simultaneously seducing and playing off of each other Regan and Goneril.

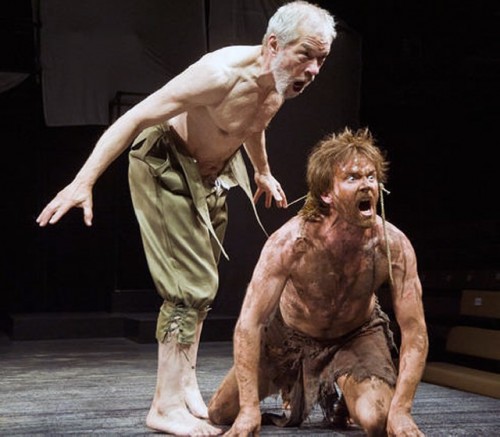

The banished brother Edgar disguises himself as a miserable wretch in the wilderness. As this mad dog Winkles was just wonderful. There was great synergy between his scruffy persona and that of the bonkers Lear. Their pathetic state was truly poignant in evoking empathy from the audience.

In the final sequence of the drama there is yet another great challenge for Lear. By then completely mad he encounters and slowly comes to recognize Cordelia. Krausnick was masterful in conveying the gradual, complex increments as he recognized the daughter he has mistreated. Krausnick aptly depicted deep remorse and slowly clawed his way back to sanity. It was riveting to witness such a difficult transition so convincingly.

Apparently, Krausnick has been obsessed with Lear for some time. Nearly fifteen years ago he directed Olympia Dukakis in The Lear Project. She returns this season in The Tempest. More recently he has taken Lear on the road and now returns with it to Lenox.

Krausnick’s Lear is on the short list of its greatest performances during our era. It is a fitting keystone in the dramatic arch of a great career.