Jessica Hecht’s Poignant Blanche DuBois

A Streetcar Named Desire at Williamstown Theatre Festival

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 24, 2011

A Streetcar Named Desire

By Tennessee Williams

Directed by David Cromer

Scenic Design, Collette Pollard; Costume Design, Janice Pytel; Lighting Design, Heather Gilbert; Sound Design, Joshua Schmidt, Fight Director, Thomas Schall; Dialect Coach, Stephen Gabis. Production Stage Manager, David De Santis; Production Manager, Jeremiah Theis; Casting, Calleri Casting.

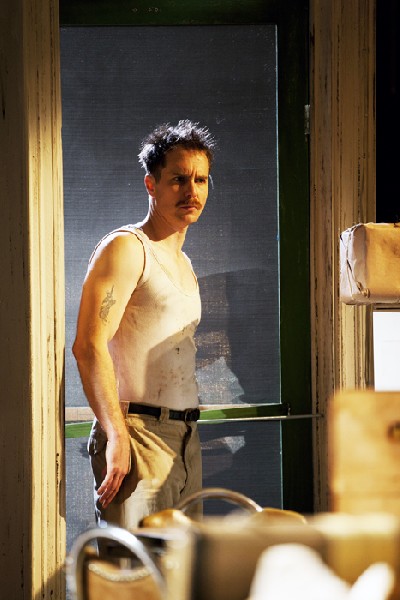

Cast: Jennifer Engstrom (Eunice Hubbell), Crystal Lucas-Parry (Negro Woman), Ana Reeder (Stella Kowalski), Sam Rockwell (Stanley Kowalski), Daniel Stewart Sherman (Harold Mitchell, Mitch), Jessica Hecht (Blanche DuBois), Lou Sumrall (Steve Hubbell), Luis Vega (Pablo Gonzales), Michael Bradley Cohen (A Young Collector), Peter Albrink (Ensemble), Vella Lovell (Mexican Woman), Kirby Ward (Doctor), Emily Ryder Simoness(Matron)

Nikos Stage

Williamstown Theatre Festival

Williamstown, Mass.

June 22- July 3, 2011

Last night, on the smaller of two, the Nikos Stage, Jenny Gersten launched her tenure as artistic director of the renowned Williamstown Theatre Festival with something old and blue, the 1947 American classic, A Streetcar Named Desire, by Tennessee Williams.

By starting the season with a proven chestnut of American theatre Gersten broke with the received perception of the Nikos Stage as a laboratory for the development of new plays. It has been the norm for a selection of works to move on to Off Broadway in New York. It seems like a conservative decision to open with long proven material. On the Nikos Stage we anticipate risk taking and not just evoking comparisons to other Berkshire companies.

In 2009, Julianne Boyd, the artistic director of Barrington Stage Company, created a well received, straight up version of Streetcar as a vehicle built around its perennial leading man, the tall, dark and handsome, Christopher Innvar. He mostly got the upper hand in exchanges with Kim Stauffer as a compellingly vulnerable Blanche DuBois.

For those seeking signifiers of what to expect from the Gersten era there is much to ponder with this safe bet and soft launch of the season. It begs the question that, if you are going to run with classic material, well, what are your going to do with it? How to give it that distinctive WTF signature? Like American Repertory Theatre do we expect a galvanic, precedent setting deconstruction? Would we stagger out of the theatre in a state of shock and awe as is so often the case at ART?

Last night we experienced a very solid, compelling, absorbing and poignant rendering of Streetcar. There were experimental tweaks and innovations that clearly set this production apart from the norm. But also an approach that falls short of the kind of bold unique markers that one associates with WTF. No, this was not just another Streetcar, but it hardly wrote a new chapter in the history of a great company.

This production directed by David Cromer established a new sense of transparency. Literally. We actually saw through the set, a clunker designed by Collette Pollard, to several rows of seats. It was like living in an apartment complex and seeing through your neighbor’s windows. We were seated in the last row, center. In the intimate Nikos there are no bad seats. During intermission I asked a colleague who was seated on stage for his thoughts. He loved the up close and personal impact particularly during the steamy mating scene between Stanley (Sam Rockwell) and Stella (Ana Reeder). He revealed intimate details which I would blush to share with you. From our distance, in the dim, moody lighting by Heather Gilbert, the sex scene was less arousing.

During a long dark scene with Mitch, Blanche, who fears that any strong light will reveal her age, there is just a single candle on stage. While evocative, the dancing in the dark sequence is so opaque that we were unable to obeserve any of the expressions and nuances of the actors. Then a spot catches our attention as it illuminates the young, closeted, poetic husband of Blanche, a suicide. It was effective but forced and a toss up as a director's decision.

While bare, transparent, raw and edgy the set was also problematic. There was a thick, broad diagonal line formed by stairs leading to the second floor apartment. This created obstructed sight lines at key moments. Playing to two sides, front and back, also meant that the actors were fully visible about half the time. During a key moment outside the apartment between Blanche (Jessica Hecht) and Mitch (Daniel Stewart Sherman) the actors were invisible. We saw his back and had to rely on their voices to understand the dramatic development.

Streetcar is very specific to a time and place. It is set in the working class, shabby and run down, but romantically evocative, French Quarter of New Orleans. Even if the Quarter was well past its prime in 1947 we agree with Blanche who is shocked at the miserable living conditions of her sister Stella. They had been raised as Southern Ladies and the Kowalskis live in a impoverished environment furnished with a hodgepodge of yard sale furniture and props. This rough interior, crudely hacked into two rooms, could have been any slum this side of Calcutta. It is hardly what Tennessee Williams had in mind.

Of course jazz is a key element in the culture of New Orleans. The music and sound design of Joshua Schmidt, while strong and compelling, was out of sync with the period represented. The musical elements greatly enhanced the drama but the era and style were wrong, wrong, wrong. The gifted combo was more post bop, Archie Shepp and Cecil Taylor than Louis Armstrong, Preservation Hall and Jelly Roll Morton. Even Fats Domino, Professor Longhair or Dr. John would be more appropriate. Where was the mojo and gris gris? So the music took us out of rather than into the period.

Of course Stanley, Polish and working class, cuts against the notion of elegant Creole tradition. It is exactly the contrast needed to set him up as crass and neanderthal in exchanges with Blanche a fading blossom of Southern womanhood. But Stanley is savvy enough to evoke the unique and complex Napoleonic Code of Louisiana law. The state’s bar is among the most difficult to pass as it calls for mastering the old, grandfathered, French law as well as American law. With its rich and complex confluence of Spanish, French, Native American, Caribbean, African American and Creole heritage New Orleans is the most global and flavorful of all American cities. This production, beyond the wonderfully drawn cameo of Blanche, made little attempt to convey that unique gumbo.

On every level Hecht’s Blanche is the heart and soul of this production. It is a brilliant feat of casting. For this performance, in her eighth season at WTF, Hecht, one of the finest stage actresses of her generation, has been given one of the truly great and challenging roles in the American canon.

In crafting this magnificent performance, one of the most brilliant and compelling presented by WTF in recent memory, Hecht has plunged deeply into all the dark and fragile corners of a desperate, proud and refined woman who is down on her luck and quickly running out of options. The arc of her descent ever deeper into memory, loss and ultimate madness is handled with stunning nuance. Hecht can turn on a dime from one mood to another. She is a survivor breathing the vapors of a tank run dry.

She is welcomed with care, warmth and compassion by a solidly presented Stella. The sister does her best to act as a thin barrier between the vulnerable Blanche and her primitive animal of a husband Stanley.

The casting of Sam Rockwell as Stanley is very much against type. The role was established by the sexiest man on the planet, at least in 1947, Marlon Brando. Barrington’s casting of Innvar evoked that tradition. But the smaller, scrawny, cocky rooster of Rockwell brings a terrifying energy to Stanley. It is a bit harder to imagine the chemistry between a couple that happens in the dark with the colored lights. But he slams around the set with such reckless abandon that he evokes a human tornado destroying all in his path. His rendering of the famous “Stella, Stella” speech is given a compelling new twist. He slams and pounds at the set like a bantam weight boxer.

For all his crass working class ways Stanley is also smart and scheming. As long as Blanche, putting on all those phony airs, is sleeping under his roof and sucking up his booze, she is fair game. He lays into her no holds barred. The sparks fly when they come head to head.

When Blanche casually mentions that they have lost the family plantation and fortune, under Napoleonic law which gives him half of his wife’s property, Stanley wants to see the papers. Ripping through her trunk he sees all the elaborate gowns, furs and junk jewelry as evidence that she has squandered their inheritance. With brilliant understatement Blanche produces reams of paper work and accounts of all those expensive family funerals. Generations of forbears had sold off lots of land to subsidize their “fornication.” That diamond tiara, which she wears while slipping into madness, is made of rhinestones. Stanley doesn’t know the difference and declares that he will hire a lawyer to look into the papers.

While creating the illusion of a lady with refinement and manners there are dark secrets. She almost convinces the lonely Mitch that she is a woman of taste and quality suitable for marriage. Mitch, here nicely played by Sherman, is willingly duped. Until Stanley, who has investigated her sordid past, reveals to him that Blanche had a parade of lovers at the flop house The Flamingo Hotel. We learned that she was fired from a teaching job for seducing a seventeen year old student. When she flirts with and kisses a young delivery boy we see that she has a difficult time keeping her hands off “The children.”

Jessica Tandy won a Tony in the original production directed by Elia Kazan. For the London stage production, Sir Lawrence Olivier, who directed, cast his wife, Vivian Leigh, as Blanche. Kazan chose Leigh as Blanche in the film which starred Brando in his second film (1951). As a vulnerable sexual predator, then 38, it is speculated to what extent Leigh drew on her own troubled psyche to portray Blanche. In the greatest role of her career Leigh set the benchmark for Blanche. We found not a shred of Leigh in the fresh interpretation by Hecht. Which, indeed, having that Socratic standard, made us all the more involved with catching the drift of Hecht’s interpretation. Her Blanche was more notable for differences than similarities.

When confronted Blanche reveals every grim detail to Mitch before asking him to leave. Instead of the Flamingo she says that she resided at the Hotel Tarantula there to lure her victims. With him her last hope departs. There is nothing left. Just delusions that an old beau is inviting her to join him on a Mediterranean cruise.

The downward spiral is inevitable and accelerated by a final rape scene with Stanley. That night Stella is delivering their baby. In a macabre twist Stanley dresses in the silk pajamas of his wedding night as he assaults his wife’s sister. What a cad.

While a long evening filled with dark shadows and obstructed sight lines this production reached deeply into the hidden secret niches of our soul and psyche. Jessica Hecht will long be remembered for an indelible Blanche. She was beautifully supported by a superb cast, particularly Rockwell, who made us forget Brando and think of Stanley in a fresh, horrific, ferocious new way.