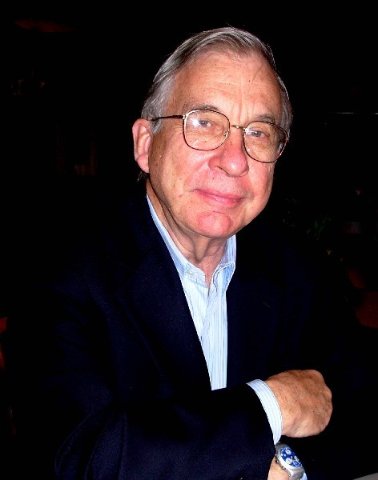

Theodore E. Stebbins of the MFA

Former Curator of American Painting

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 22, 2020

Theodore E. Stebbins discusses the M&M Karolik and William H. and Saundra Lane collections. On his watch Stebbins acquired major American, modern and contemporary works. His legacy for the museum and in the field is formidable

Charles Giuliano Were you appointed by Jan Fontein?

Ted Stebbins First he appointed John Walsh as the Baker Curator of European Paintings. It was the early months of 1977. Walsh urged Jan to appoint a curator of American paintings. Jan appointed me in the summer of 1977. I began that September or October.

CG Ken Moffett had started as the first curator of contemporary art, appointed by Perry Rathbone, in 1971. As Jan told me he was an Orientalist with no expertise in painting. There had been no curator of paintings since before Rathbone. This was the domain of directors. But Fontein felt that it was important to have curators.

TS Rathbone was pretty knowledgeable and he was his own paintings curator. He loved going into the market and buying European paintings.

CG My sense was that he was a generalist with no field of expertise. He was part of the group of future museum directors who studied with Paul Sachs at the Fogg Art Museum (Harvard). He was essentially a connoisseur/ amateur.

TS A great scholar is not necessarily a great curator. Perry had a hunger for acquisitions and he had a good eye. On the whole he bought wonderful things for the MFA. Rosso Fiorentino's "The Dead Christ with Angels" (1524-1527) is one of the great Italian masterpieces in America. He showed the Susan Morse Hilles Collection and tried to get the Peggy Guggenheim collection to Boston. He and Hanns Swarzenski bought a great Brancusi which sadly was stolen in 1981. The museum proceeded to use the insurance money to buy European silver. What a shame. He had Swarzenski buying very good works of decorative arts.

CG The legacy of Rathbone and modernism at the MFA would have been different if he managed to secure the Hilles and Guggenheim collections. Together Perry and Hanns bought a late Picasso “Rape of the Sabine Women.” What is your opinion of that painting?

TS It was a weak acquisition. It was so much fun for them to have lunch with Picasso. Curators and museum directors are people and being with the greatest artist of the 20th century must have been an immense experience. At the time it must have looked like a very important painting. A little scholarship wouldn’t have hurt in this case.

CG When I interviewed Fontein in 1984 he had visited the late Picasso exhibition at the Guggenheim which included the MFA picture. A colleague told him that “Rape of the Sabines” was to the late period what “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was to early Picasso. He told me that if you are going to have a later work by Picasso it’s good to have the best.

TS There are different views. I prefer the earlier Picasso when he’s bolder and more inventive. It wouldn’t have been what I would have chosen but I can understand them choosing it and I can understand their argument for it being an important work.

CG I would like to explore the process of building collections particularly the Karolik and Lane collections. Maxim Karolik preceded you but you were involved in the Lane acquisition. What would the American collection be without those two great acquisitions?

What I had heard is that Karolik came to Rathbone and was advised to collect in this neglected and then affordable period of American art. From your recent museum lecture, hosted by Matthew Teitelbaum, I got a different sense of how that happened.

TS Perry had nothing to do with Karolik other than fighting with him a lot. The collection was fully formed and, in the museum, when Perry got there. Karolik and his wife, who was a decedent of one of the great Boston families, worked together on the collections. She was a Codman but descended from Elias Hasket Derby (1739-1799) from Salem. He had a great house as well as furniture and silver. That was already in the MFA. Karolik helped her to build on an already existing collection. In 1938 they gave it to the museum. They were ahead of their time in insisting on a scholarly catalogue of the collection. That included furniture and some Copleys.

By then, his wife was eighty and he was looking around for something new to collect. He was in his forties and full of energy. He visited an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum called Life in America. It was 1939 and his eyes were opened to American landscapes and genre painting.

He started to collect Thomas Birch (1779-1851) a Philadelphia painter. Then, through Charlie Childs, Fitz Henry Lane (1804-1865) the Gloucester seascape painter. Then Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), Thomas Cole (1801-1848), John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872), George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), and William Sidney Mount (1807-1868), among others plus many works by folk artists. He started during the war years and the collection was virtually finished by 1945.

(Maxim Karolik, 1893-1963, an opera singer of Jewish heritage, was born in the Ukraine. A linguist, he taught himself English before emigrating to America. He met Martha Catherine Codman (1858-1948) during a performance in Washington, D.C. She was 34 years older. They married on the Riviera on February 2, 1928. They were largely snubbed by society. They lived in Newport where she died in 1948. They were equal partners in every sense.)

Very few people were collecting that material. There were a few but just enough to keep the dealers having lunch. Childs in Boston, Victor Spark in New York, and several others.

Those paintings looked so much like 19th century Russian paintings. That may have influenced him. That has astonished people because the most frequent comment is how American they are.

CG That’s a major point of the Robert Rosenblum, H. W. Janson text book 19th Century Art (1984). It widened the focus from a fixation on French art to include German, Russian, British, and Scandinavian art. In particular, it changed the thinking about the uniqueness of American Luminism (the focus of the Karolik collection). Using that as the new standard text changed how 19th century art was taught. Luminism as uniquely American was the thesis of Barbara Novak.

TS Exactly. John Wilmerding did a big show of luminism at the National Gallery.

(American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-1875, 1980)

My essay in that catalogue discusses German, Danish and Russian paintings. I was saying, hold on a minute, American art was part of an international phenomenon.

CG The night before my master’s exams at Boston University, I reread that catalogue. As luck would have it one of two questions was to discuss American landscape painting from 1850-1875. The night before the next day’s exams, I read the Brooklyn Museum’s catalogue on The American Renaissance. That proved to be one of two questions I answered. There was also the shift from the term luminism to the glare aesthetic.

TS You’ve got that wrong. Wilmerding was a champion of luminism. Except for my essay, the whole catalogue is based on luminism. Pretty soon after that William H. Gerdts, who died recently, wrote an essay called “The Glare Aesthetic.” It was about another group of painters just after the luminists. Wilmerding was strictly a luminism guy.

CG Regarding the Karolik collection, you mention Mount and Bingham who were not part of the luminist tradition. What was the Bingham in the MFA? Was it “Shooting for the Beef” (1850)? No, wait, it’s owned by Brooklyn.

TS I wish it was that’s a great picture. Very good, you just passed the orals. It’s owned by the Brooklyn Museum. When I was at Yale, I longed for that painting. A great Yale collector, Francis Garven, had sold it.

CG What was the Karolik Bingham?

TS He had a couple, “Wood-Boatmen on the Missouri” and we also had “The Squatters” (provenance Henry L. Shattuck, 1937). I sold one in not very good condition to buy the Stuart Davis (1892-1964) “Hot Still Scape,” jointly with Mr. Lane, perhaps the single most important painting in my career.

CG What was the Mount?

TS He owned several including one called “The Bone Player.” (Also “Rustic Dance After a Sleigh Ride” and oil sketches “The Barn by the Pool” “The Fence on a Hill” and dozens of drawings.)

CG “The Bone Player” is one of the most important Mounts.

TS It absolutely is.

CG Particularly because of the sympathetic manner in which African Americans are depicted in his paintings.

TS There was so much caricature in art at that time as you know but Mount portrayed the black man as a fully intelligent equal.

CG As did (James Goodwin) Clonney (1812-1867) who you sold. (One of six paintings by Clonney all from the Karolik Collection.)

TS Somewhere in there I sold a Clonney but there were several others in the museum. I think that Clonney is more caricatured than Mount but we can argue that.

CG I first saw a number of Binghams in St. Louis.

TS That’s the place to see them.

CG I’ve never been to Long Island to see the Mounts. We saw “Eel Fishing on the Setauket” in Coopertown at the Fennimore Museum. It conveys the wonderful relationship with the black woman standing to spear fish and the boy steering the boat.

When you talk about great collections there is the frequent story of the one that got away. What was Karolik’s problem with (Frederic Edwin) Church (1826-1900)?

TS He thought he had a great one “The Finding of Moses” but by a minor painter. It was one of his few mistakes. He should have bought one or two others but for some reason Church was harder to grasp. When Barbara Novak wrote her book “American Painting in the 19th Century” (1969) she skipped Church altogether. Like all Harvard graduate students, we went straight to the MFA and studied the Karolik Collection. For some reason, Church was harder for her, Wilmerding, and I to grasp. For some reason Karolik was also weak on Sanford Gifford but that gap I managed to fill.

CG How did so many paintings by Church end up in the Wadsworth Athenaeum?

TS I’m not sure. Daniel Wadsworth owned all the Coles that are there. Church was from Hartford. But if those Church paintings are ones that Daniel Wadsworth owned, I don’t remember.

CG Where does Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) come into the Karolik Collection?

(There are 26 MFA works by Bierstadt of which 24 are in the Karolik Collection.)

TS The Bierstadts in the Karolik collection are very good. He liked Bierstadt a lot. He was the first to buy Bierstadt’s oil sketches. There are ten or fifteen sketches on paper like the one on the wall behind me. Nobody was collecting them. They were studies for paintings and didn’t seem collectable to people. Karolik was a pioneer in many ways.

CG Looking through the list of your acquisitions you also bought Colonial paintings including (John) Smibert (1688-1751).

TS There was a lady in Brookline who gave us a beautiful pair of Smiberts. I bought Benjamin West’s (1738-1820) great “King Lear” from the Boston Athenaeum. One of my first purchases was a charming Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) of a young woman “Anna Powell Mason.” It was at Vose’s and I thought it was the most beautiful Stuart I had ever seen. I went back to the museum which had 40 Stuarts and there was nothing as beautiful.

I built on strength. I bought a full length (John Singleton) Copley (1738-1815).

CG That was the “Nathaniel Sparhawk.”

TS Yes. The museum had 50 Copleys but no full-length portrait. When you are a curator of that kind of collection you want to cement it as the absolute best. To see Copley people absolutely have to come to Boston.

CG As I understand it Copley and portrait painters charge by how much of the body is in the picture. As well as how many individuals. So, as a full-length portrait, the Sparhawk would have been an expensive portrait.

TS Copley also charged by size. You could buy a miniature and that was much less. You could buy a pastel the size of a book. He charged more for the larger pictures because the sitters’ arms and legs and backgrounds were difficult to paint. If you paint a couple it’s much more because you have to blend them together.

CG I wonder if he charged more for all the fruit in “Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwaite.” He was a shrewd businessman starting as a teenager. Yale owns Smibert’s “The Bermuda Group” which is a complex composition. He holds up well.

TS That’s one of the landmarks of American art.

CG He was trained in England so do you think of him as American or British school?

TS He was American enough. We were short of artists and needed everybody we could find and write about. Whistler, Sargent all those people were equally American.

CG (James Abbott McNeill) Whistler (1834-1903) claimed that he was born in St. Petersburg where his father worked as a military engineer. When reminded that he was born in Lowell, Whistler responded “I will be born when and where I choose.”

Prior to the Lane Collection with the Karolik Collection how does the MFA compare to other American museums in the area of American art?

TS In 1980, when I had been there a couple of years, the best collection of American Art was the Metropolitan Museum’s. Boston was second, and The National Gallery third. By 2000, twenty years later, with the Lane Collection and all these other additions, I acquired 400 paintings, about a fifth of the whole collection. By then you could argue that the MFA had the best American collection.

In those 20 years the Met did very little. The National Gallery with John Wilmerding and curator Nick Cikovsky were very active. By 2000 the MFA and National Gallery had the major collections of American art with the Met now in second place.

CG In my 1984 interview with Jan Fontein I quote a comment from you at that time saying that within the next ten years the MFA would have the nation’s best collection of American art.

TS I don’t remember saying that. Even for me that would be a bit of hubris because collecting takes a lot of luck. But it’s right that I was ambitious.

CG How did the Lane collection come about? Speaking of luck where would the MFA be without the Lane and Karolik collections?

TS I kept noticing when I went to shows like Marsden Hartley I was seeing great pictures that said “Lent by the William H. Lane Foundation.” Who was this? I discovered that he lived near Worcester. I wrote to him and said “I would like to come and see you.” It was a day like today crisp and clear. John Walsh and I drove out. We had a noon appointment. I knocked on the door, barely touched it, and it flew open. This big guy, shaped like you, said “Where have you guys been?”

We staggered back and thought, oh my God, are we late, “I thought our appointment was for twelve.” He said “No, where have you been for the past twenty years?”

CG That seems like a good question.

TS Then I discovered that, I think you have this in one of your interviews, Perry Rathbone, whom you underestimate, had discovered who he was and put him on a committee. Then Lane gave one of those colored Franz Klines (1910-1962) to the MFA.

(Susan Morse Hilles, gave a major Kline, “Probst 1,” 1960 to the MFA in 1973)

At some point Perry told Ken Moffett to go see Lane. He went and saw the collection and Bill (Lane) said “What do you think? What can we do together?” According to Bill, Ken said, “I don’t think there’s much here for the MFA.” I hate saying that because it’s so sad.

CG As much as we liked Ken, he was narrow.

TS He was narrow but is it possible to be that narrow? How would you turn down Kline, (Hans) Hofmann (1880-1966) (Arthur) Dove (1880-1946) and (Charles) Sheeler (1880-1965)?

CG In my interview with Fontein I asked, in view of the weakness of the collection, why was Moffett’s turning down gifts? He asked for an example and I told of how Moffett turned down the pick of (Philip) Guston’s (1913-1980) studio. Moffett was not interested in his current work and asked for an older abstract expressionist work. That request was rejected and years later the museum acquired a Guston which was likely not as good as what the artist had initially offered.

TS That’s the sadness and mystery of Moffett who was a very nice man as you know. When I got to the MFA he was the first curator to invite me to lunch. He was a serious and good scholar but he should never have become a curator. He was perfect as a scholar who could have written all the books he wanted about his specialty. But a curator needs a broad vision.

We’re inclined to blame Ken but that was exactly the point of view that the MFA wanted when they hired him in 1971.

CG What you really mean is that’s what the trustee Louis Cabot wanted.

TS Yes, Louis Cabot and a group of other collectors. But ever since Michael Fried’s 1965 exhibition, at the Fogg, Three American Painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and Frank Stella. Boston area collectors had been in love with color field; that was modern art as they saw it. The Fogg immediately bought a big Morris Louis (1912-1962). By the time that Ken got to the MFA that was Boston’s taste and where they wanted to go, Color Field paintings.

CG During that time when you visited American museums that was what you saw in lobbies and contemporary galleries.

TS I have spent a lot of time sorting out the differences of taste between New York and Boston. It’s interesting to see what a curator can do like Sam Hunter (1923-2014) at Brandeis in his five years (1960-1965). Every other Boston collector and curator rejected the ‘crudity’ of Pop art and New York taste, sadly. That was a decade earlier than Ken. The Rose still has the best collection of modern art in the area.

CG I was an undergraduate when Hunter was the first director of the Rose Art Museum. As a journalist for The Justice I wrote about him, particularly for ignoring undergraduates. He held a huge Poses Foundation colloquium after graduation. Many New York artists came and were put up in the dormitories. It was a who’s who from Motherwell to Guston. I lived in Brookline so I saw what other students missed. The entire NY art world came for his Larry Rivers opening. The champagne never stopped flowing and Larry played sax with his jazz ensemble.

With a gift of $50,000 from the New York collector Leon Mnuchin, and his wife Harriet Gervitz-Mnuchin, Sam made numerous studio visits and bought some 25 works. Hunter told me he might have bought a single work but wisely spent it on emerging artists.

Bill Seitz was director after Hunter. We had lunch with Frank Stella at the Faculty Club. Because of student and faculty involvement with radical politics giving to Brandeis dried up. There was a minimal budget when Carl Belz took over at the Rose.

I often visited and interviewed Belz. He pulled out thick acquisition folders which we went through. The most Hunter paid was $3,000 for the Jasper Johns (B. 1930) painting “Drawer.” A Claes Oldenburg (B. 1929) “TV Dinner” was a couple hundred dollars. When Brandeis president Jehuda Reinharz tried to sell the collection in 2009, it was estimated to be worth some $300 million. The collection was founded in 1961 and had grown to 7,000 works. The MFA in that period pales by comparison to the Rose. It is a great example of how vision and risk taking are crucial to establishing great collections.

TS There should be a statue of Sam Hunter next to the Rose. He’s never gotten enough credit.

CG I knew and liked Ken. We could not have been more different in taste but had a very cordial relationship. At the MFA he was open to working with guest curators.

TS What curators did he work with in Boston?

CG John Arthur did a very successful Richard Estes (B. 1932) show. Chris Cook, then director of the ICA on leave from the Addison Gallery, did a Douglas Huebler (1924-1997) show. It was a time when the ICA was in transition at the Parkman House on Beacon Hill before its move to Boylston Street.

When the Evans Wing was closed for renovation Ken was assigned to curate the MFA’s temporary galleries at Quincy Market. One of his most amazing projects was the Anthony Caro (1924-2013) York Series of metal sculptures. They were displayed on Mass Avenue on the grassy area in front of the Christian Science Church.

TS The Caros were wonderful and stand up well.

CG Of course there is a great tragedy of what he was trying to do. His strategy was to make formalism the focus of the contemporary collection. The crown jewel was to be the Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) masterpiece “Lavender Mist” (1950). It was Merrill Rueppel who rejected that acquisition.

TS Who actually ended it was Betty Jones who was the head of paintings conservation. She loved to give negative opinions about pictures. She did the same thing when the great John Trumbull (1756-1843) “The Sortie from Gibraltar” from the Boston Athenaeum was offered for sale. The Met bought it immediately after the MFA turned it down. She did that with “Lavender Mist” and the trustees in that situation were looking for an excuse not to go ahead. She was a much beloved and trusted person at the museum. That was the end of it.

I wasn’t there at the time. But if the curator and director really believe in something, they can get it done. As you point out the director didn’t back it but the curator has to be willing to fall on his sword. That’s your legacy. That’s what you live for. To get that work into the museum.

CG Ken told me the story chapter and verse. He went with the truck to Long Island to pick up the painting from (Alfonso Angel Yangco) Ossorio (1916 –1990). He convinced the collector to sell Pollock’s masterpiece for under a million dollars. Then the disaster with the acquisition’s committee. In his version they called in “the new man” (Rueppel) and he was the one who raised the issues of the stability of the surface. What if some of the paint flaked off? That’s when the conservator was called in stating that she had no experience with that kind of painting.

Imagine the contemporary collection if its centerpiece was “Lavender Mist?” Also, he had a very good David Smith (1906-1965) “Cubi XVIII” (and “Vig VII).

I understood that Wayne Andersen of MIT had proposed the “Cubi” for City Hall Plaza. That didn’t happen. In fact, there are no works of art on that vast open space.

TS I don’t know about that.

CG Going back to Lane he may be described as eccentric. Everything he bought had to fit into his station wagon. He was on a mission and loaded it to bring works to New England libraries, small museums, and schools. His intent was to use the collection to educate people about modern art. When an exhibition ended, he packed it up and drove it home. That had been going on for years before its acquisition by the MFA.

Most of the work was purchased from the Downtown Gallery.

(Edith Gregor Halpert (née Edith Gregoryevna Fivoosiovitch) 1900–1970. Her Downtown Gallery was founded in 1926.)

TS That’s correct but he went to other galleries as well. When the weather was nice, on weekends, he would drive to New York in a big old Chevy station wagon. And yes, the works had to fit. He would take a dozen or so pictures and look at them during the week. He would select one or two and take the rest back the following weekend. So, it was constant looking and learning.

CG He visited the studio of Franz Kline.

TS He knew Kline well.

CG The colored paintings were in the studio during a time when the artist was evolving to black and white paintings. Lane preserved a transitional period.

TS Exactly. Lane was an instinctive scholar. He never graduated from college but he wanted to know the roots of the art. When he bought an artist, he wanted to know what the early work looked like. He did the same with Hofmann and Dove.

He asked Kline for advice. He said, I’ve got you and Hofmann, who else should I be collecting? Kline said you should go see Jackson Pollock. Lane went to the Broome Street Bar. Pollock already had too much to drink and was rude to Lane. He went home and never bought a Pollock. That could have been a turning point (for the collection).

CG There were famous collectors who were bargain hunters. They would visit studios and try to strike deals to buy a number of works at cut-rate prices. That often resulted in acquiring a phase or moment in the artist’s development. That happened notably with Walter Chrysler and Joseph Hirshorn.

I worked with Lester Johnson on a traveling exhibition of his work. He told me how (J. Patrick) Lannan came and said “How much is this one? How much is that one? Then how much for all of them.”

TS Roy Newberger would do that. He would visit a gallery exhibition and buy the whole show.

CG Did Lane do that? Was he a bargain hunter?

TS Not at all. He never bargained and always paid the price that was asked. The strange thing is that the most he ever paid was the same amount that was the most that Karolik ever paid. Which was $2,500. Edith Halpert showed him the Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) of the deer’s head. It was a classic O’Keeffe. Lane said “OMG I can’t believe it is still available.” He thought he was very lucky because everyone else with education and taste was buying School of Paris.

My theory is that great collectors are often outsiders like Karolik and Lane.

CG Another bargain hunting collector was Walter Chrysler. He had a museum in Provincetown before establishing one in Norfolk Virginia.

TS He was known for collecting fakes.

CG I have done research on Provincetown artists. He bought them in depth so the museum is key for that research.

If we may move in a different direction. You sent me some of your essays as well as a video disc of the MFA interview with Matthew Teitelbaum. Reading histories of the early years of the museum, its directors, trustees and collectors, there is the perception of a commitment to collecting the artists of Boston from colonial times through the present.

The museum has had major exhibitions celebrating that legacy including New England Begins; The Seventeenth Century, Paul Revere’s Boston, Back Bay Boston: The City as a Work of Art, The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930, The Boston Tradition: American Paintings from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Paintings by New England Provincial Artists, 1775-1800, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870-1940.

These survey exhibitions end between 1930 and 1940. That’s precisely when there was a paradigm shift and the leading Boston artists were immigrants and individuals of Jewish heritage. There was a recent show of Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death but the MFA has no interest to create a survey of Boston artists in the post war era.

During your MFA lecture you discussed anti-Semitism that Karolik experienced. You collected Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951) and Edmund C. Tarbell (1862-1938) in depth but not the Boston expressionists; Hyman Bloom (1913-2009), Jack Levine (1915-2010), and Karl Zerbe (1903-1972).

TS I particularly liked Zerbe’s work. Lane and I had a long negotiation about what he was going to include in our acquisition. I got the Hyman Bloom of the female corpse which I always liked. And I got two Zerbes including “Job” a wonderful painting. You and I disagree on this but I thought this represented them well. I was never enthusiastic enough about their work to form a large collection of their work.

CG This is the first time that I’m hearing this. To be honest I’m astonished. Those are such important acquisitions. The Bloom female corpse is a major picture and one of the great pieces in the Lane collection. What was your role in that? The “Job” is also a great Zerbe. How did that fall in place?

TS There they were in the Lane collection. Very few pictures were on the wall (of his home). He had a storage area in his house, like in a museum, where everything was on racks. I should pull out for you from my archive a couple of earlier proposals. I would write to him and say we would like these sixty or seventy pictures. He would write back and say “You’re an idiot.” (laughing) So I would start again. I can’t exactly remember the sequence.

CG In what sense were you and idiot?

TS I don’t think he used that word but he would say you’re on the wrong track. I was asking for too much of this and not enough of that. I wasn’t doing well enough by Sheeler say, or Dove. Honestly, I forget the details of that. For a future conversation I could probably reconstruct it.

CG Who bought the Bloom? Who bought the Zerbe? Did he buy those paintings?

TS He owned them.

CG So you weren’t involved in their purchase?

TS No. (off mic) I’m looking for my catalogue of the Lane Collection. He bought the Bloom from Durlacher Brothers in 1958. That was a pretty late acquisition. By then he had mostly stopped. He already owned them and I had nothing to do with their original acquisition.

CG He never bought a work by Jack Levine.

TS No. He didn’t like figurative painting. He was interested in abstract painting.

CG Aren’t Bloom and Zerbe figurative?

TS They are more abstract than Levine. Basically, Lane was very much an abstraction guy but he must have seen the abstract strengths of Bloom and Zerbe. Levine was an excellent painter but didn’t have that same sense of underlying abstraction. It’s possible that’s how Lane viewed it.

CG Did you see the MFA’s Bloom show?

TS My protegee Erica E. Hirshler did it.

CG Did it change your thinking about Bloom?

TS She did a fantastic job and I also saw the Bloom show at the Alexander Gallery in New York. I read Erica’s book very carefully. She made the best possible case for Bloom. I took a lot of different people through that show trying to get people to look at it.

CG The question is, did it change your opinion of the artist?

TS It enriched my view. There were a lot of paintings I had never seen before. It didn’t change the way I would rank him.

CG Ok, how do you rank him?

TS I rank him as a very interesting not quite great painter. Because of his local background, absolutely worth showing at the MFA and worth acquiring.

CG When you were a curator at the Fogg Art Museum did you ever visit the prints and drawings room and view the juvenilia of Bloom and Levine? As teenagers they were students at Harvard of Denman Ross.

TS I did. They were both terrific draughtsmen.

CG When you were a Fogg curator why was it never discussed to show that work?

TS I thought there were better things to show.

CG (laughing) OK. But considering the importance of these two artists, that they were native Bostonians, their unique relationship to Harvard and the Fogg. Their relationship to Denman Ross. One could think of so many reasons to organize an exhibition of their work owned by the Fogg. It’s a tremendous oversight not to show that work.

(Hirshler included some of the Fogg’s Bloom drawings in her MFA exhibition.)

TS I didn’t do it. I’m guilty. In another five or ten years (at the Fogg from which he is now retired) I might well have. They are very good drawings and I love showing things that haven’t been seen. Underrated and so on.

CG How do you respond to the notion that you failed to collect Boston artists after the era of the American Impressionists? How can you be such a supporter of Benson, a saccharine, mediocre painter, and fail to see the genius of a painter of corpses? I can’t understand that.

(The 1969 publication “American Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston” lists eight works by Benson, six by Tarbell, one by Bloom, two by Jack Levine including one from the WPA, and none by Zerbe. The Lane collection doubled Bloom to two works and added two by Zerbe. The museum continues not to have a major work by Levine. It is anticipated that the Hirshler exhibition will result in gifts of works by Bloom.)

TS Nobody is perfect. I was only in charge of contemporary art (at the MFA) for two years. Mostly my bailiwick didn’t include the Boston expressionists. When the Lane collection came, I might say I could have gone into that. But I thought I had more important things to do.