Shop Talk With Artist Richard Criddle

Behind the Scenes at Mass MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 22, 2009

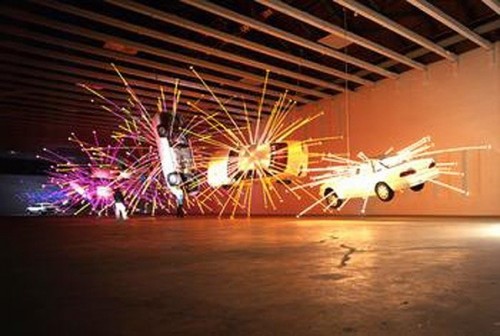

Life size sculptures of elephants and tigers riddled with arrows, flipping Ford Taurus cars, a two story house, an abandoned movie theatre, trucks, an entire amusement park, a Chinese Dragon Boat, a sprawling sculpture assembled from stacked, ersatz cement "Jersey Barriers," these are just some of the daunting "materials" that artist Richard Criddle, the head of the installation and fabrication crew at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art has dealt with in the past decade.

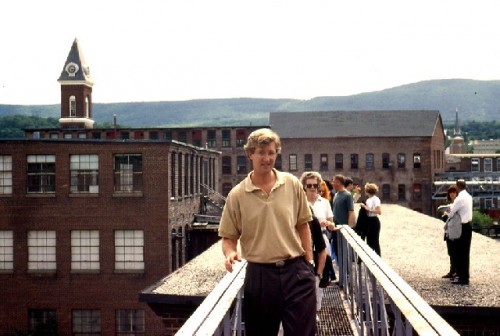

On the occasion of the anniversary of the world class museum in North Adams, Criddle took time out from his formidable day to day responsibilities, to put together a Power Point presentation of some of his most interesting projects, challenges, and collaborations with artists. Following the talk he conducted a tour of the back side of the galleries explaining how they manage to actually get those enormous elements into the building. This culminated in a rare glimpse into the wood and metal shops where the projects come together.

When not solving all those installation issues for Mass MoCA he and his Huskie, Winston a fixture in the shops, drive home a short distance to Vermont where he works on his own, large scale, multi media sculptures with a narrative twist. There is also studio space for his wife Debora Coombs one of the foremost artists in the medium of stained glass. Their daughter is currently attending art school in Canada. The British family came to America, just over a decade ago, because Debora was involved with major projects that entailed relocation of the studio. In London, Richard worked in high end fabrication and when he showed a portfolio to Mass MoCA's founding director, Joe Thompson, he was hired on the spot.

A while back, when Criddle showed his sculpture at Kidsspace in Mass MoCA, we got together to talk about the work. Last summer I included two of his sculptures in an exhibition "What's So Funny" at the Eclipse Mill Gallery. It was a bit tricky because just as we were installing the Criddles were scheduled to drive to Toronto to get their daughter settled for her freshman year. Richard and his fellow installer, Jason, managed to get the enormous, complex pieces set up with remarkable efficiency. They looked just fantastic and it was exciting to see them in a different space with more breathing room.

Just how do you get automobiles to flip through the air while sending off those spikes of light simulating fire works? Richard told the audience that the initial reaction when presented with these tasks by curators and artists is something like you've got to be kidding. Add a few colorful expletives. Then he gets to work solving the problems. Not that they all go well. He has his own private thoughts about the relative success of individual projects.

One that got away was the aborted project with Christoph Buchel intended for the vast space of Building Five that ended in court. The artist made constant demands that the museum was not able to meet as the installation went well over the limits of time and budget. There was the threat of a $10 million law suit. This also held up the exhibition program during prime season when the installation was masked by hanging tarps. It became something of a game for visitors to peek in when the guards weren't looking.

While Criddle has a lot to say about Buchel, off the record, he showed great restraint during the lecture by commenting that he could solve every problem presented to him with the exception of "Mr. Buchel's attitude."

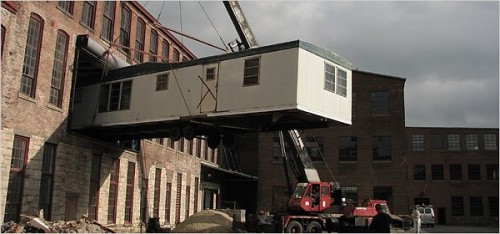

Although he did not include Buchel's installation shots in the presentation he did show us a trailer being hoisted into the gallery. That image has been widely published. He also showed the process of cutting a two story house into five sections to be installed in the gallery. I asked how long it had taken to remove the cluttered gallery following a court decision in favor of the museum? He stated that it went rather quickly. The last object in the space was a facsimile of the house which Saddam Hussein occupied prior to his capture. It had been constructed by Buchel and his assistants. With some glee Criddle described how, at the end of a long day, he got in the fork lift, put the pedal to the metal, and ran the length of the gallery at top speed. He smashed into the house. We assume that he vented a lot of frustration.

The selection of images of works in progress was intriguing. But he commented that they are somewhat rare. "We are too busy making and installing the work to have the time to take pictures" he said. "Most often we photograph when there is a crane on site moving something into the building (like that elephant sculpture just barely making it through a gap in the wall where a window was removed). Or someone happens to have a camera or cell phone handy."

While Mass MoCA got back on track after the Buchel mess with an installation by Jenny Holzer, the negative experience has had a great impact, not just on Mass MoCA, but museums in general. It has resulted in significant changes regarding contracts and commitments with artists. One would safely assume that having been so severely tested the museum has emerged every stronger and more focused. Since then, Mass MoCA has completed its Sol LeWitt project, widely viewed in the media as a triumph, and is moving forward with increasing its endowment as well as contemplating further development and renovation.

The original plan for Mass MoCA, under the visionary Tom Krens, prior to Joe Thompson's involvement, was for the museum to function as a warehouse for large scale works of minimal art on long term loan from private collectors and museums without sufficient space to show these works. This is the strategy of Dia Beacon in New York which is most often compared to Mass MoCA. Early on it was decided that Mass MoCA would rotate exhibitions which were on view on average for a year.

During an early stage of the development of the Mass MoCA project, under Krens there were negotiations with Count Giuseppe Panza di Buono to install many of the works in his collection. While reporting on this for Art News I had the occasion to talk with Count Panza by phone from his home in Varese, Italy. By then Krens was the director of the Guggenheim and he had staff on site working with the collection. Around this time there were several large works by Mario Merz in the yet to be renovated galleries. The intent was to give some sense of how the spaces would be developed to display large scale works. They were removed prior to the opening of the museum.

What appears to be the current mandate is a mix of changing exhibitions, refreshed annually, as well as long term exhibitions such as the installation of work by Joseph Beuys, which has been on view for several years, and the Anselm Kiefer works which will come down next year after two and a half years. The Sol Lewitt installation, which is housed into its own building, is contracted with the Yale University Art Museum, which owns the conceptual pieces, to remain on view for 25 years. The museum is considering acquiring a permanent collection. If building Six is developed, now filled with works from prior exhibitions in storage, it is anticipated that it will display long term installations of work by major contemporary artists.

One interesting question entails plans for the building leased by the neighboring Clark Art Institute. Its space is located under the Mass MoCA sign and visitors pass it on the way to the museum's entrance. While focused primarily on 19th century art the Clark is inching into the 20th century and modernism. This summer, for example, the Clark is showing Georgia O'Keeffe. If some of that work were on view at Mass MoCA it would surely be a win win for both museums. Thompson has worked closely with Michael Conforti, the director of the Clark, to create synergy. Mass MoCA has opened a shop on Spring Street in Williamstown in renovated space in front of Images Theatre. While Mass MoCA strengthens its ties to Williamstown many feel that it could do a lot more to help revitalize hard scrabble North Adams. This summer, for the second time, however, it will participate in the DownStreet project. Its Kidspace will have a project on Main Street.

We wanted to know just how he managed to get those Ford Taurus cars to flip through the air in Building Five during an exhibition of work by Cai Guo Qiang? Criddle's manner of solving the problem was quite pragmatic. On line he purchased several model cars which he spray painted white. From the early days of developing Mass MoCA there exists a large scale model of the space.. Using wire he was able to mount the toy cars in the model. When the artist visited through an interpreter Criddle was able to explain to the artist that he could manipulate the cars. He described the artist as like a "kid in a candy store." Once it was agreed how he wanted them arranged it was just a matter of measuring and converting to scale. The cars were then mounted to beams and suspended from the ceiling.

The cars were purchased from local dealers who agreed to remove the motors and transmissions and deliver them painted white. The installation later traveled to a museum north of Montreal. Eventually the work was purchased. For the artist's mid career retrospective a new set of cars was purchased and installed in the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum with spectacular impact.

As a young museum with limited resources and a fixed budget it is often daunting to realize the vision of an artist. An Ann Hamilton installation in Building Five, for example, entailed devices designed to slowly drop sheets of paper which fluttered down into the gallery. During the run of the exhibition Criddle reported that amounted to some 13 million sheets of paper. To comply with local fire department codes the space had to be entirely emptied from time to time and the waste paper taken to be recycled.

The machine presented by Hamilton, designed by her staff, proved to be expensive and complicated. With the permission of the artist Criddle took it apart, examined the components, redesigned it and purchased surplus parts. He was able to create some 40 devices given the budget. The original machines were so costly that the museum could only have afforded to provide four. Following the exhibition the 40 devices were broken down to their components and sent to the artist. She is apparently recycling the elements for further projects.

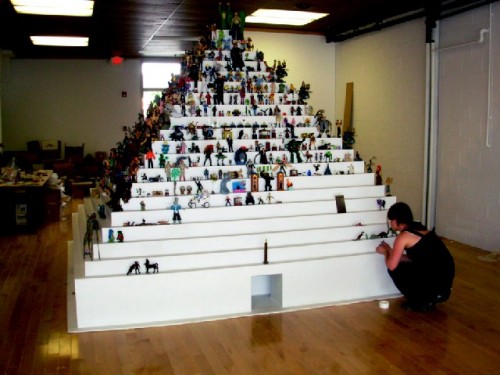

Works created for exhibitions become the property of the artists. But there are contractual agreements regarding fees for their further exhibition in museums. There are also commissions on sales. The intent is to recover some of the cost of fabrication. In some instances, such as the stepped pyramid of toys by Jarvis Rockwell (a version of which is included in DownStreet) work is stored at Mass MoCA. But Criddle stated that artists are encouraged to take the work with them. Sometimes materials get recycled such as the wooden beams that were a part of the Robert Wilson "Stations."

Because useful materials get salvaged when possible Criddle wonders what will happen if Thompson develops Building Six. Where will be put all of the stuff that is stored there? Even with seventeen acres Mass MoCA is running out of space. A lot of what is owned on the campus has been leased and this helps to create revenue.

During the talk Criddle discussed trying to maintain a fine line in working with artists to develop a project. He feels strongly that it is their work and ultimate decision. With more mega scaled projects entailing crews, assistants and fabricators it is becoming increasingly murky as to exactly how to define and credit the many specialists involved with creating the work. At the end of a big budget film, for example, it can take fifteen minutes to roll the credits. Many of these technicians and designers are recognized for their work with Academy Awards. While the director has the final say it is understand that film is a collaborative effort. This hasn't yet happened in the field of the fine arts.

So far Criddle is not anxious to see his name on the wall in a list of credits. This may happen from time to time in a catalogue or in the credits for a video. But it is not a priority. He recalled how years ago he visited the studio of Henry Moore. There was a crew at work on various aspects of the sculpture. Although confined to a wheel chair the artist was still in complete control of everything that came out of the studio.

But isn't it true that for some artists their ideas are sketched out on the back of a napkin? Yes, this does happen to some degree, but Criddle stated there are many artists who are quite specific with spectacular plans and drawings. They know exactly what they want. He described how advances in communications and technology have been a great asset in developing works. By e mail and fax he is able to maintain close contact with an artist, arguably half way round the world.

More and more major artists are having their works fabricated in China and other nations. The work can be executed at a fraction of the cost of assembly in the U.S. or Europe. The current exhibition in Building Five "The Nanging Particles," by Simon Starling, is an example of this development. The stainless steel sculptures were forged and polished in Nanging, China. The project conflates with a time when Chinese workers were used as strikebreakers in North Adams. There are enormous photo murals in the exhibition illustrating the workers posed in front of a factory.

Following the slide lecture Criddle led a group on a tour. He pointed out the large steel door on the outer wall of Building Five. It is one of the few positive results of the Buchel project. Prior to that it was necessary to remove windows. He also explained that now it is possible for an on site fork lift to be used to move works into the space. The crates from China, for example, were opened outside and Starling's sculptures were easily moved into the gallery.

The tour ended in the 2000 square foot wood working shop and the metal shop that adjoins it. The spaces seemed simple and efficient. He discussed how much of the equipment had been donated; including from a decommissioned nuclear power plant. "They were gone over with a Geiger counter before we got them. So we don't glow in the dark."

At the end of the tour with Criddle there was a sense of how the process of making art has really changed in the last decade. And how contemporary museums, like Mass MoCA, and the circuit of international Biennials, are playing an ever greater role in fabrication and realization of an artist's vision. Indeed, it takes a village. For Criddle and Mass MoCA anything is possible. The impossible just takes a little longer and costs more.

.