Emotional Impact: American Figurative Expressionism

April Kingsley's Catalogue for Michigan State University

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 19, 2014

Emotional Impact: American Figurative Expressionism

By April Kingsley

Michigan State University, East Lansing, 2013

172 Pages, illustrated, with notes on the artists and index

ISBN 978-1-60917-373-9 (e book) ISBN 978-1-61186-084-9

From 1999 to 2011, the critic and art historian, April Kingsley, served as curator of the Kresge Art Museum at Michigan State University which opened in 1959. With limited resources the decision was made to collect Figurative Expressionism. It was a more affordable extension of her focus on Abstract Expressionism. Previously Kingsley published “The Turning Point: The Abstract Expressionists and Transformation of American Art” (1992).

This new book is a catalogue for the collection she assembled over a dozen years. In 2011 The Kresge closed and its assets were transferred to the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum which opened at MSU in 2012 in a building designed by Zaha Hadid.

Because there has been scant scholarly study, or even a workable definition of the movement, it remains a generic category. When in doubt about work in the gap between Abstract Expressionism, a return to the figure, and emergence of the New Realism (Pop Art) then label the artist a Figurative Expressionist.

Casting a broad net, including artists whom Kingsley knows from Provincetown and New York, this publication further obfuscates the definition of an important but poorly understood second generation Post WII American art movement.

There has yet to be an intellectually rigorous, thoroughly researched, major museum exhibition or scholarly publication that nails down Figurative Expressionism. There are divergent threads for a zeitgeist which informed the studio practice of like minded artists simultaneously in Provincetown, New York, Chicago, Boston and the Bay Area of San Francisco. Kingsley recognizes this but seems to get the balance wrong.

Adam Zucker an emerging scholar of Figurative Expressionism and later Rhinohorn movement organized “Pioneers from Provincetown: The Roots of Figurative Expressionism” Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Provincetown, MA (July 19 – September 2, 2013). For that exhibition the catalogue included critical essays. Many of the artists in the exhibition had shown in Provincetown’s experimental Sun Gallery of Yvonne Anderson and Dominic Falcone.

It is correct for Kingsley to move on from Abstract Expressionism but her map lacks direction. Many of the artists in this publication studied with and branched off from Hans Hofmann in New York and Provincetown.

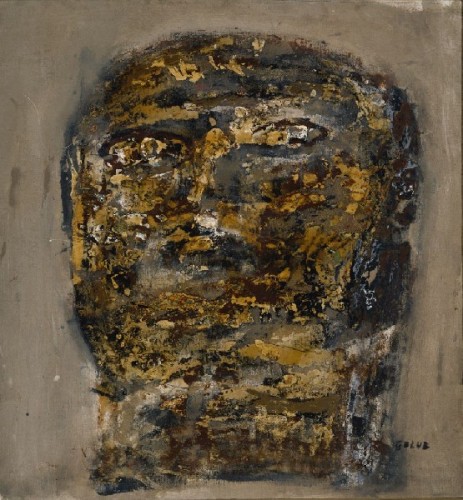

Problems with artists in the Kresge collection may stem from limited funding. Kingsley’s essay states the primacy of Jan Muller and Bob Thompson in Provincetown, David Park in California, but perhaps they were too expensive, however essential, to the collection. She does not mention Leon Golub from Chicago whose early work was essential to the movement. Golub’s wife, Nancy Spero, should also be a part of the dialogue.

Of the all important Provincetown group she focuses on Robert Beauchamp who is minor compared to his brother-in-law, Lester Johnson. Jay Milder, Wolf Kahn and Nanno de Groot are discussed but there is no mention of Tony Vevers, George Segal, Earl Pilgrim, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, Bill Barrell and others before and after the all important Sun Gallery.

These major players are omitted while improbably she includes- Sideo Fromboluti, Nora Speyer, Selina Trieff, and Robert Henry- established Provincetown artists who are not well defined by Figurative Expressionism. Kingsley acquired and writes about a number of peripheral artists that seem at best a stretch.

If ever we are to make sense of Figurative Expressionism it is important to start with artists who best represent and define the movement. Begin by demarking the boundary separating Abstract Expressionism and the beginning of Figurative Expressionism. At the other end close enrollment before figuration elides into Pop.

Her check list includes Willem de Kooning and Elaine de Kooning as well as Grace Hartigan. Wrong. They are abstract expressionists and including them obscures the issue.

It is key to establish that a generation of artists, although informed by Abstract Expressionism, were determined not to repeat its formulas. As Kingsley notes the figure remained in de Kooning’s women and returned in late Pollock. Their figuration was an influence but doesn’t belong in an attempt to define a new and separate movement. The time frame she covers was too early for Guston’s evolution from abstraction to figuration which inspired the similar but different Neo Expressionists.

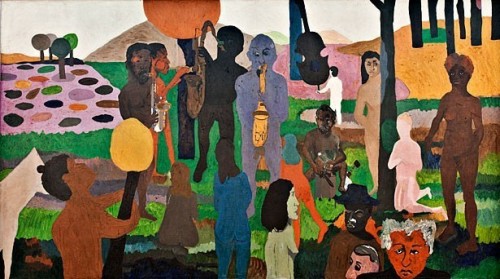

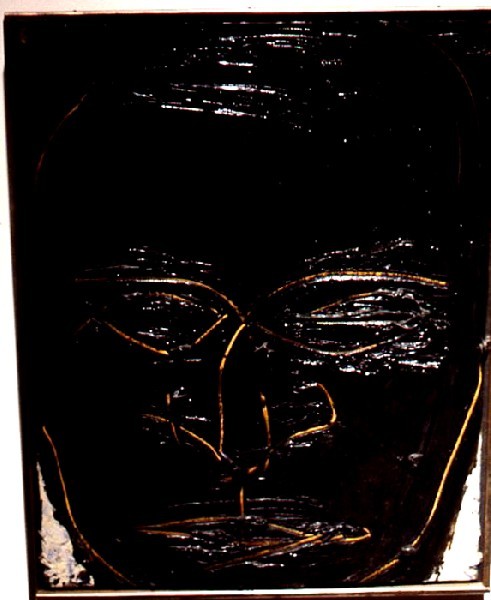

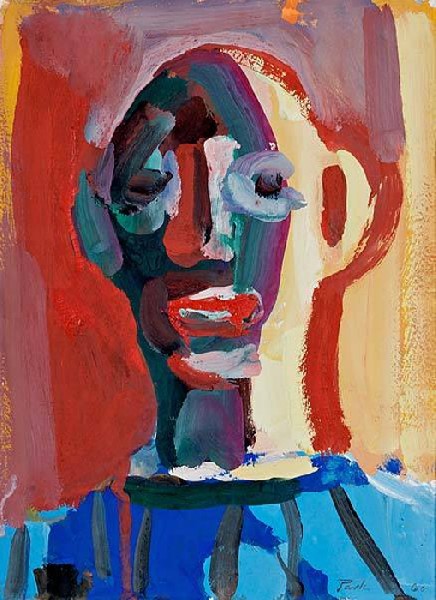

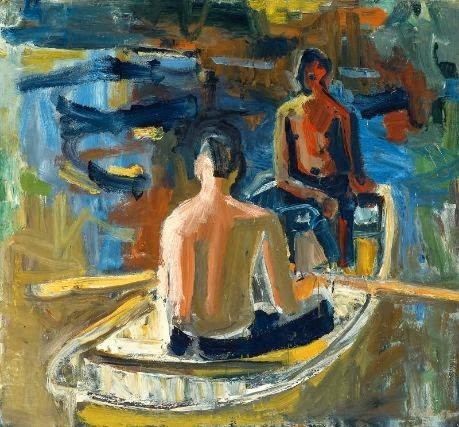

With roots in Abstract Expressionism Kingley focuses on thick, distorted and loosely applied paint. That works when applied to George McNeil or Jan Muller. This doesn’t, however, embrace the lyricism of the linear high chroma paintings by Bob Thompson or the more subdued, abstracted minimalism of Tony Vevers. Figurative expressionism informs aspects of the early work of Alex Katz, George Segal and Wolf Kahn.

The movement is not defined by a specific look or technical approach. It is more about a state of mind and commitment to experiment and change. Kingsley is correct in stating that the work of no two artists in her book looks the same. But the critical assessment that a return to the figure was reactionary is inaccurate. The degree of radical commitment is essential to defining a figurative expressionist. Too many of the artists Kingsley selects are conservative, not tough enough, decorative and illustrative.

One test of theory is finding a confluence among artists separated geographically but with uncanny similarity in their approaches. In particular I think of the big, sweeping, universal man paintings of Park in California and the large, iconic, early heads that Johnson was creating in New York and Provincetown.

It has become too common to treat the Bay Area Figure artists as separate. Arguably they are better known than the Sun Gallery group but there are many points of commonality. Kingsley never connects the dots or even speculates on why figurative expressionism was a national phenomenon.

With this publication it appears that Michigan State University has completed its commitment to Kingsley and her collection. It will be up to a new generation of curators to determine its role and function.

Future reputations of collections reflect the acuteness, the eye of the curator and ability to back up affordable acquisitions with scholarly publications. That appears to be lacking here. This generally mediocre book is unlikely to cause much interest or debate in the field.