The Boston Early Music Festival Just Smashing

Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center June 21-23

By: David Bonetti - Jun 18, 2013

Youth, Genius and Folly

The Boston Early Music Festival

June 9-16, various venues

Almira: Königin von Castilien” (Almira: Queen of Castile)

Music by George Frideric Handel

Libretto by Friedrich Christian Feustking

Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs, music directors

Gilbert Blin, stage director and set designer

Caroline Copeland and Carlos Fittante, choreographers

Anna Watkins, costume designer

Cast: Almira: Ulrike Hofbauer; Edilia: Amanda Forsythe; Fernando: Colin Balzer; Consalvo: Christian Immler; Osman: Zachary Wilder: Raymondo: Tyler Duncan; Bellante: Ulrike Hofbauer; Tabarco: Jason McStoots

Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra; Robert Mealy, concertmaster

Boston Early Music Festival Dance Ensemble; Melinda Sullivan, ballet mistress

Cutler Majestic Theatre, Boston

June 9, 12, 14, 16

Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center, Great Barrington

June 21, 22, 23

La Descente d’Orphee aux Enfers (Orpheus’s Descent into Hell) and La Couronne de Fleurs (The Crown of Flowers)

By Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Boston Early Music Festival

Jordan Hall, New England Conservatory, Boston

June 15

Shalin Liu Performance Center, Rockport

June 17

Morgan Library and Museum, New York City

March 17 & 18, 2014

Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs, musical directors

Gilbert Blin, stage director

Anna Watkins, costume designer

Melinda Sullivan, choreographer

Robert Mealy, concertmaster

Cast (La Descente d’Orfée aux Enfers): Orphée: Aaron Sheehan; Euridice: Carrie Henneman Shaw; Apollon: Olivier Laquerre; Ixion: Jason McStoots; Tantale: Michael Kelly; Titye: Olivier Laquerre; Pluton: Jesse Blumberg; Proserpine: Mireille Asselin; Shepherds, Shepherdesses, Shades: Megan Stapleton, Lydia Brotherton, Caitlin Klinger, Thea Lobo, Alexis Silver, Carlos Fittante, Olsi Gjeci.

Cast (La Couronne de Fleur): Flore: Mireille Asselin; Shepherds and Shepherdesses: Jason McStoots, Michael Kelly, Jesse Blumberg, Aaron Sheehan, Carrie Henneman Shaw, Lydia Brotherton, Thea Lobo, Megan Stapleton; Dancing Shepherds and Shepherdesses: Carlos Fittante, Olsi Gjeci, Caitlin Klinger, Alexis Silver

Last week, the sounds of theorbos, lutes, chittaroni, rebecs, bagpipes, hammer dulcimers and ouds along with an odd Irish harp, crumhorn, lirone, santur and kanun, not to mention more mundane harpsichords, violins and violas – and let’s give a shout-out to the human voice – resounded throughout the theaters, concert halls, churches, libraries and museums of the city of Boston. (Did I fail to note that a violin and viola, allegedly owned and played by Mozart, were making their American debut?)

It was the week of the biennial Boston Early Music Festival, this year devoted to the theme of “Youth: Genius and Folly,” and for lovers of early music, it was the best week of the year in Boston, if not in the entire world.

Celebrating the 17th installment of what has become a major cultural institution, it featured two operas, 16 official concerts, two mini-festivals of organ and keyboard (harpsichord, clavichord and fortepiano), each with three concerts, lectures, master classes and symposia, a trade exhibition and more than 100 fringe concerts, sometimes starting five an hour, all featuring early music specialists from all over the western world.

When I moved back to Boston three years ago, the BEMF was one of the major draws. (So, alas, was Filene’s Basement.) This year I took full advantage of it, although some might say I was merely skimming the surface. I attended six concerts and both operas in a period of five days. I heard Emma Kirkby, accompanied by lutenist Paul O’Dette, sing songs by John Dowland, one of her specialties; the Italian group La Risonanza, with the alluring soprano Roberta Invernizzi, perform cantatas by Handel composed in Rome and London; Chicago’s Newberry Consort perform Galician-Portuguese “cantigas”; the British group Atalante sing early 17th century Roman cantatas by the underappreciated Luigi Rossi and his homies; Jordi Savall’s Hespèrion XXI perform music from cosmopolitan 17th century Istanbul from Ottoman, Armenian, Greek and Sephardic Jewish traditions; and a party-hearty program of drinking songs from Germany by the protean group Tragicomedia, the baby of festival co-director Stephen Stubbs.

And, of course, the two operas offered: “Almira,” George Frideric Handel’s first opera, written for the Hamburg Opera in 1704 when he was 19, and a pastiche of Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s “La Descente d’Orphée aux Enfers” and “La Couronne de Fleurs,” both written about 1685, the year Handel was born.

It was exhilarating but also exhausting.

“Almira”: It’s easy to forget that Handel was German, so closely is he identified with London where he wrote oratorios in English and operas in Italian. But German he was, born in Halle in 1685, although he didn’t stay in Germany for long. By the time he was 20, he had gone to Italy, where he learned the suave Roman style of vocal writing he would practice, indeed perfect, during the rest of his opera career. After a brief spell back in Germany in 1710, he decamped for London in 1712, the place to be for an ambitious artist at the time, where he wrote operas, oratorios and anthems as an independent artist, unattached to the court.

But he wrote “Almira,” his first opera, in Germany, in Hamburg, where there was a large and ambitious opera company. Although he had been writing music since he was a child – he was a musical prodigy – “Almira” is the oldest work of his that survives, his default Opus One.

“Almira” was a back-door commission. The composer originally commissioned to write it had abruptly left Hamburg after having just starting it. Handel, who was playing in the orchestra, jumped at the opportunity and wrote the work, inheriting an absurd libretto. This is not quite the “star-is-born” scenario it might initially seem, however. Handel had already been commissioned to compose for the company, which was hungry for new work, the opera that was scheduled to follow “Almira.” (That opera, “Nero,” is now lost.)

Although it made for a thoroughly enjoyable, if long, evening, “Almira” is no masterpiece. We are interested in it primarily because it is the first work of a composer who wrote some of the greatest operas in the repertory, most of which have been revived only in the last 50 years. Now that Handel’s hits are regularly appearing on international stages, it’s time for the obscurities. And obscurities are what the BEMF has become known for presenting during its biennial festival. It doesn’t do obscurities for the sake of doing obscurities, however; its intention is to help restore to the repertory works of merit that have fallen by the wayside.

The opera can also be seen as a source-book for those who know Handel’s mature works well. Several themes that he developed more fully first appear here, most notably the melody that became “lascio ch’io pianga” in “Rinaldo,” one of his greatest scores. In “Almira,” the theme is not totally there yet, but Handel knew he had something in embryo and he came back to it and turned it into one of his most hummable arias only a few years later.

The plot of “Almira” is ridiculous and filled with unnecessary complications that prevent dramatic situations from fully developing, although even at his young age Handel shows great skill in delineating character through sung texts. And, to be sure, there are a number of showpieces, which hint at the genius to come.

Briefly, Almira has been crowned queen of Castile after the death of her father, who, in his will, requires that she marry one of the sons of his trusted advisor Consalvo. The rather ridiculous fop Osman decides he is the son to seek her hand and thus become king. Almira is not pleased. She is secretly in love with her secretary Fernando, who is secretly in love with her. What should be easy is not, however. Fernando is an orphan, found washed up on the shore, and thus not of noble blood. Also in the court is the Princess Edilia, who had expected to marry Osman, and is furious that he has ditched her for a chance to wear the crown. To complicate matters, a Moorish Prince has come to Castile to woo Almira. There is another princess, Bellante, in the court, who doesn’t have much to do, but is necessary so that in the end, when the principals are matched up – it turns out that Fernando is really Consalvo’s long lost son - there is a woman for the feckless Osman. Oh, yes, there is also Tabarco, ostensibly Fernando’s servant, but in fact a jester straight out the commedia dell’arte.

The plot doesn’t really matter. This is not an opera that seeks to explore the deeper meanings of life. Its purpose is to entertain, and the plot is just a skeleton on which hang a number of delightful arias and ensembles. Even at 19, Handel proved himself to be a showman, an audience pleaser, and even though it groaned at the unlikely plot developments – and aughed outright lwhen Fernando’s parentage is revealed - the audience seemed to be thoroughly entertained.

A large part of the pleasure was in the beauty of the production. For its biennial Centerpiece Opera, the BEMF is devoted to presenting operas in line with authentic period performance practice both in the pit and on the stage. During the past quarter century music lovers have gotten used to music written before circa 1800 played on period instruments according to the best knowledge at the moment of how those instruments were played. Authentic stage productions are far fewer. They require scholarship and special training for the performers, which take time and money. But when it all comes together musically and dramatically, as it does in “Almira,” it is an experience worth waiting for.

(This is a radically different approach from that taken by Craig Smith and his forces at Emmanuel Music 30-odd years ago. Musically, the orchestra and singers pursued an authentic sound and style, at which they often succeeded brilliantly. However, the productions were given over to the ever-adolescent Peter Sellars, whose “updated” notions frequently undermined the meanings of the original texts and the excellence of the performers. His post-modern, deconstructive approach sometimes yielded insights, but more frequently took the opera in a direction the composers and librettists would never have countenanced. He was lucky that Handel and Mozart were dead by the time he trifled with their works.)

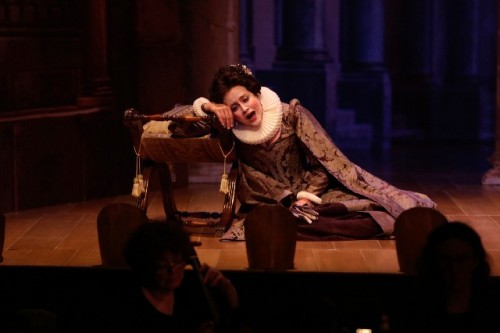

Credit here for balancing scholarship with showmanship goes to stage director and set designer Gilbert Blin, who first directed a BEMF opera in 2001 and has served as the festival’s stage director in residence since 2008. He is profoundly knowledgeable about period performance practice and set design and with the BEMF is able to put his knowledge into practice. What might initially seem to us highly stylized acting becomes over the length of the evening a perfect correlative to the opera’s musical language. Blin directs his singers in the gestures and postures current when the works were composed until it becomes natural to them.

Blin’s set designs are a delight. It is amazing how convincing in practice shifting flats on which illusionistic scenes are painted can be– and how fast the scene can be switched from a private room in a palace to a city plaza to a formal salon to a garden.

He is aided and abetted by costume designer Anna Watkins, whose knowledge of period style matches his. Her use of luxurious fabrics helps make the visual stage picture rich and sensuous. Dance is an important element in the totality of Baroque opera, and choreographers Caroline Copeland and Carlos Fittante – and their corps of dancers - kept the movement light and fluid. Concertmaster Robert Mealy led his crack period orchestra with vigorous but lithe direction. Their individual contributions come together brilliantly at moments such as the ballet of the continents in Act III, a synthesis of the arts that hints at the gesasmtkunstwerk a later German composer named Wagner strove to create.

Of course, the focus of the evening was on the singers. Baroque opera cared as much for beautiful singing as the 19th century bel canto period. Handel was one of the greatest composers for the voice, and that greatness was evident even in “Almira.”

As we have come to expect, the BEMF assembled a cast of young singers totally in tune with Baroque period style. As a group, all of them were fine and a few were brilliant.

Although Handel wrote stirring arias for male singers, he favored, as so many opera composers do, the higher female voice. In “Almira,” he wrote roles for three sopranos.

For Almira, he wrote a series of lovely arias that touch on longing, heartbreak and the pains of love. For the jilted Edilia, he composed classic rage arias. For Bellante, the most undeveloped role, he nevertheless wrote a number of lovely arias.

As Almira, German soprano Ulrike Hofbauer, an almost last minute substitute for the Argentine singer Veronica Cangemi who had visa problems, had the classic high, pure, crystalline early music voice. She was quite touching in a Act I aria of longing, “Chi piu mi piace voglio,” that states for the first of several times her frustrations that she can’t marry the man she loves. (The text of the opera is primarily in German, but a few of the arias are in Italian, which was the practice at the time.) Unfortunately, Handel made her a sort of one-note character, and she has few opportunities to sing anything other than songs of heartbreak.

Boston soprano Amanda Forsythe had a more fiery role in Edilia, who is enraged by her treatment by the fickle Osman. A great singer with a beautiful voice capable of expressing feeling, Forsythe had some unexpected problems hitting high notes the night I heard her – she hit them, but with effort - but she acted more intensely than any other singer on stage, visibly seething in anger at her situation. (By the way, any fears about her vocal state were dispelled the next night when she sang for the festival pick-up group Tragicomedia a Handel cantata and a Monteverdi duet with her usual incandescence.) Still, she sang her first aria with fierceness and vocal brilliance. A rage/revenge combo, it reads in translation, “Traitor, may thunder, storms, and lightning/Strike your head,/And may Zeus with his thunderbolt/Weaken your deceitful heart.” The combination of alluring vocalism and the ability to find the drama in a two-dimensional character contributed to Forsythe receiving the biggest ovation of the evening.

As Bellante, the young American soprano Valerie Vinzant was fine.

Among the men, Canadian tenor Colin Balzer was outstanding as Fernando. If each character in the opera has a single dominant emotional color, Fernando’s is melancholy and resignation at his fate. His low tenor was perfectly suited for his unshowy music.

The other men were basically fine. German baritone Christian Immler had a nice gravelly voice for Consalvo, and New York baritone Tyler Duncan was unremarkable as Raymondo, the Moorish king. Zachary Wilder’s Osman was more complicated to judge. He sang his role weakly, but that’s the nature of his character. As an actor, he put over the role of a feckless fop convincingly.

A special word of praise for Jason McStoots’s Tabarco, who sacrificed his usual smooth tenor voice, evident in the Tragicomedia concert the next night, for the part of a mincing servant, a comic role that was almost de rigueur in Baroque opera. In this case, Blin and McStoots collaborated in creating a character that demonstrated that the “nance” existed in theater more than 300 years before Nathan Lane.

“Orphée”

Since the Charpentier double-header is a repeat performance of a 2011 production with only one significant cast change, I’ll be brief – I promise! One of the off-festival year series of Chamber Operas, the Charpentier production is more modest, without the elaborate sets of the Centerpiece Opera productions, but with Gilbert Blin’s sophisticated direction and Anna Watkins’s beautiful costumes. Like the other Chamber Operas, which are all presented at the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, the singers and dancers perform on a concert stage with the orchestra. In this case, the small chamber orchestra appeared in the center of the stage, encircled in flowers, creating a lovely stage picture.

I find the Chamber Operas to be more enjoyable than the Centerpiece Operas, mainly because they feature better operas and, in their stripped presentations, they are more “modern.” Handel’s “Acis and Galatea,” Monteverdi’s “Orfeo” and Charpentier’s “Acteon,” three earlier productions, are real masterpieces, not obscurities dug up for re-examination. And none of them last four hours!

The Charpentier evening is not as it might seem to be two distinct operas, one done before and one after intermission. It is a pastiche Blin hobbled together from two different works to create an evening’s entertainment. The problem is that Charpentier never wrote the final act of his “Orphée”; it ends with Orpheus leading Euridice out of Hades without his subsequent fatal glance back. To make it work – and the high quality of the music that remains justifies whatever it takes to bring it on stage - Blin inserted it into the middle of a vocal contest among shepherds and shepherdesses singing praises of Louis XIV. The contest is called off by Lully, Charpentier’s historic rival – this is a total fabrication by Blin - before the third act, at which point Flore, the presiding shepherdess, proclaims that all the submissions are worthy of the prize, and she shares the winner’s floral crown with all.

Seeing it a second time, I enjoyed the production even more than I had in 2011. This time I realized beforehand that there was no need to try to differentiate the various shepherds and shepherdesses: they were virtually interchangeable, singing silly songs of praise. So I was able to sit back and enjoy the enchanting music and dance. It was a delightful entertainment, which was its original intention.

The meat of the evening is the two acts of “Orphée,” which is a real drama. Once again, Aaron Sheehan proved himself to be the perfect singer for the title role. Tall, handsome, noble in bearing, he has a voice of extraordinary sweetness. I detected a greater weight to his low notes, which added to his ability to fully communicate the tragedy inherent in the myth. The scene in which he, by the power of his music, tames the torments of souls in Hades, is gorgeous and worth all Blin’s efforts to bring this work to the stage.

The rest of the cast was close to perfect, insouciant in both singing and dancing. Canadian bass-baritone Olivier Laquerre as Apollo and Pan was particularly impressive as the authoritative voice of divinity among bucolics. The female leads, Mireille Asselin as Flore and Carrie Henneman Shaw as Euridice, both sang beautifully.

The one cast change was a great disappointment: the extraordinary bass-baritone Douglas Williams, up until this year a BEMF regular, did not repeat his role as Pluto. His replacement, Jesse Blumberg, did a fine job, but it was impossible to get the memory of Williams’s powerful voice out of my mind.

The BEMF has begun to take its Chamber Operas on tour. Last year it took its great production of “Acis and Galatea” on the road, to Seattle, Kansas City and New York. It intends to do the same with its “Orphee” pastiche. Already it has been done in Rockport and there is a planned tour in the winter of 2014, with the dates at New York’s Morgan Library set.

And this year as in the past the Centerpiece Opera is being taken to Great Barrington, where it will be done this weekend.

It also plans to continue its recording project. This summer both “Acis and Galatea” and “Orphée” will be recorded in Germany. Touring and recording are good for both the festival and its young performers, many of them local. The BEMF is already famous within the early music world. The tours and recordings will help to let the rest of the world see how good it really is.