The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City

Peabody Essex Museum Opening September 14

By: Ariel Petrova - Jun 17, 2010

When the last emperor of China, Puyi, left the Forbidden City in 1924, the doors closed on a secluded compound of pavilions and gardens deep within the palace. Filled with exquisite objects personally commissioned by the 18th-century Qianlong (pronounced chee’en lohng) emperor for his personal enjoyment, the complex of lavish buildings and exquisite landscaping lay dormant for decades. Now for the first time, 90 objects of ceremony and leisure — murals, paintings, furniture, architectural and garden components, jades and cloisonné — will be on view at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts. The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City will reveal the contemplative life and refined vision of one of history’s most influential rulers with artworks from one of the most magnificent places in the world.

A model of international cooperation, the exhibition was organized by the Peabody Essex Museum in partnership with the Palace Museum, Beijing, and in cooperation with World Monuments Fund (WMF). The Emperor’s Private Paradise will travel to The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Milwaukee Art Museum in 2011. “This is a very exciting, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for our visitors to see the contents of this extraordinary Forbidden City complex before it opens to the public at large in 2019. Our collaboration with the Palace Museum and World Monuments Fund underscores PEM’s commitment to showing ambitious, world-class exhibitions and to our ongoing cultural exchange with China,” said Dan Monroe, Executive Director and CEO of the Peabody Essex Museum.

A garden of elegant repose

A jewel in the immense Forbidden City complex, the Qianlong Garden had remained untouched for more than 230 years when in 2001 the Palace Museum and WMF began the restoration of the 27 buildings, pavilions and outdoor elements including ancient trees and rockeries. Built when China was the largest and most prosperous nation in the world, the garden complex was part of the emperor's ambitious commission undertaken in anticipation of his retirement. Buddhist shrines, open-air gazebos, sitting rooms, libraries, theaters and gardens were interspersed with bamboo groves and other natural arrangements. In the garden’s worlds within worlds, the Qianlong emperor would retreat from affairs of state and meditate in closeted niches, write poetry, study the classics and delight in his collection and artistic creations.

“The Qianlong Garden project is the centerpiece of our conservation work in China. World Monuments Fund is honored to be part of both the history and the future of this important site, and delighted to be working with the Peabody Essex Museum and bringing the Qianlong Garden to a public audience,” said Bonnie Burnham, President of World Monuments Fund.

The Emperor’s Private Paradise includes a film and other interactive elements highlighting the conservation process undertaken by the Palace Museum and WMF, as well as the gifted artisans who restored the objects and architecture to their original condition. A computerized walk-through will offer visitors a vicarious experience of one of the principal structures, the Juanqinzhai building, conservation of which has just been completed. Museum-goers will be able to try their hand at calligraphy with a touch station that will lead them through the brush strokes.

An emperor of exceptional influence

Reigning from 1736 to 1796, the Qianlong emperor led China to sweeping administrative, military and cultural achievements while far surpassing European monarchs of his day in wealth and power. As the fourth emperor of the Qing (pronounced ching) dynasty to rule China, his 60-year reign spanned the American and French Revolutions, and the reigns of a veritable parade of Georges, Fredericks and Catherines of Europe. The Qianlong emperor was a multi-faceted monarch — an aggressive military conqueror of vast territories and a passionate patron of the arts. Many of our impressions of imperial China’s splendor date from the 18th-century, and owe much to the tastes, fashions and style of the Qianlong court. While incorporating classic Chinese design features such as elements of nature and expressions of Confucian morality, the Qianlong emperor also added new concepts from European painting styles. His desire to innovate within the Chinese aesthetic touched the objects, architecture and landscapes that he commissioned, transforming what we recognize as Chinese art.

Objects of imperial contemplation

The artworks crafted for the Qianlong emperor echoed and supported his dedication to Buddhist spiritual pursuits, Confucian morals, love of literature and reverence for nature. “Visitors to this exhibition will be invited to walk through our galleries the way the Qianlong emperor would have strolled through his rooms and gardens. Around each corner are opportunities to encounter objects of beauty and exceptional craftsmanship,” said Nancy Berliner, exhibition curator and curator of Chinese art at the Peabody Essex Museum.

A spectacular hanging Buddhist shrine painted on silk (shown above) evokes a paradisiacal realm, radiant with color and glittering with gold. The work is a mandala, a Buddhist cosmogram depicting a portion of the universe with deities and other supernatural beings arranged in a ritually auspicious design that can aid the meditation of initiated worshippers. In an innovative combination of two and three-dimensional formats, painted figures sit nestled in glass-covered insets, dotting the piece like set gemstones. The emperor, a devotee of a form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Mongolia, is depicted in gold as the Bodhisattva Manjusri at the center.

The magnificent throne (shown right) exemplifies the exceptional craftsmanship of artisans engaged by the emperor to furnish his private world. This piece was carved from zitan, a wood so hard and dense that it sinks in water. Techniques including gold painting on lacquer, bamboo thread marquetry, fine wood carving, and jade and hardstone inlay contributed to the elegant solidity of the piece, which likely took well over a year to complete.

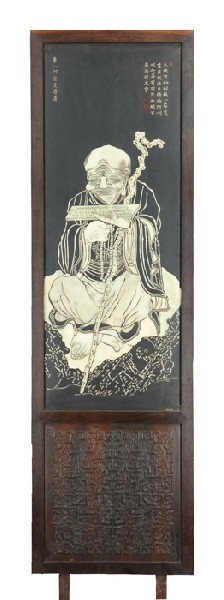

An impressive sight for Buddhist devotees or art connoisseurs is the monumental jade-and- lacquer screen (shown left) of 16 luohan, or enlightened beings –– the celebrated, quasi-legendary disciples of the Buddha. Each character is depicted in a surprisingly grotesque manner after an earlier painting by a master who saw them appear this way in a dream. Visually arresting in black and white, the reverse side of the screen is equally striking, with glorious botanical images painted in gold. Long hidden from view due to its orientation flush with a chamber wall, the reverse images were a great discovery for Palace Museum and WMF conservators working on the project.

Also included in the exhibition is one of the rare extant examples of imperial trompe-l'oeil mural painting, a fifteen-foot-wide work depicting women and children in a palace hall celebrating the New Year. The mural is one of only six such surviving 18th-century works. Painted by Chinese court artists who had been trained by a European artist, the mural reflects a successful blending of European and Chinese traditions.

Other objects range from the quietly personal to the flamboyantly crafted and hued. Calligraphy written in the emperor’s own hand conveys a sense of his refined thinking and brush technique. Panels carved in semiprecious gemstone or rendered in brilliantly pigmented cloisonné are as vibrant and pleasing as the day they were created.

China and the Peabody Essex Museum

PEM’s relationship with China extends nearly to the Qianlong emperor's reign, and is the longest of any museum in North America. Dating to the close of the 18th-century, PEM’s holdings in Chinese art and Asian export art represent some of this country's first efforts to reach outward and establish mutually enriching, lasting exchanges with other nations.

The Emperor's Private Paradise is the next step in PEM’s ongoing commitment to bringing new discoveries in Chinese art and architecture to the public. Yin Yu Tang, an 18th-century merchant’s house acquired by the museum in 2003, is the jewel of the museum’s collection and the only example of historic vernacular Chinese architecture in North America. The building was meticulously dismantled at its original site in southeastern Anhui province, and re-constructed piece by piece at the museum in Salem. Yin Yu Tang remains a great source of pride for the museum, a deep and abiding connection to China and a rare trove of living scholarship.