Edvard Munch Trembling Earth

Clark Art Institute Exclusive American Venue

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 15, 2023

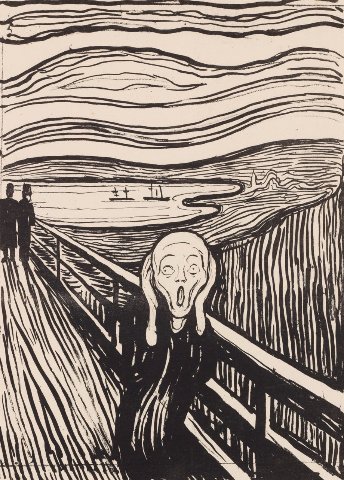

“I was walking along a path with two friends — the sun was setting — suddenly the sky turned blood red — I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence — there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city — my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety — and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature,” The Norwegian artist, Edvard Munch (1863-1944) wrote in his diary, Nice, 1892.

That cathartic experience, like Saul/ Paul on the road to Damascus, resulted in one of the singular images of 20th century art.

The Scream exists in four versions: two pastels (1893 and 1895) and two paintings (1893 and 1910). There are also several lithographs of The Scream (1895 and later). One of the pastels was commissioned by a collector. The 1895 pastel sold at auction on 2 May 2012 for $119,922,500, including commission.

He later stated that "For several years I was almost mad... You know my picture, 'The Scream?' I was stretched to the limit—nature was screaming in my blood... After that I gave up hope ever of being able to love again.”

A print of The Scream is currently on view at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth examines the lesser known role of landscapes in his oeuvre and their connection to obsessions with love, anxiety, longing, and death.

The Clark is the sole U.S. venue for the exhibition which is on view through October 15, 2023. Organized in collaboration with the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany and the Munch Museum (MUNCH), Oslo, Norway, the exhibition is presented in Potsdam from November 18, 2023–April 1, 2024, and in Oslo from April 27–August 24, 2024.

This overview of his work will come as a surprise to those familiar with his subjects the stages of life, the femme fatale, the hopelessness of love, anxiety, infidelity, jealousy, sexual humiliation, and separation in life and death.

That’s the work we encountered in a 1997 exhibition at the Shanghai Museum. It was mounted on the occasion of the Norwegian King’s visit to China. We were surrounded by school children making drawings inspired by the works.

At the Clark we have to reframe our notions of the artist in an exhibition that is both exquisite as well as profoundly scholarly.

Astute visitors will feel a flashback to the Clark’s Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway from 2021. The previously unfamiliar Astrup (1880-1928) was born almost twenty years after Munch and died younger. But there are compelling contrasts in their approach to landscape. There is more saturated chroma in Astrup as well as swatches of difficult pthalo green. While Astrup gardened for pleasure, and to feed his family, Munch was only interested in cultivating his studio and let nature reclaim his several properties (when he became prosperous). Munch’s landscapes are comparatively somber but they are both regarded as great experimental printmakers.

During WW1, however, Munch cultivated produce to feed himself and neighbors.

In that he remained in Norway Astrup is an interesting, stand alone, provincial painter. Munch, however, traveled and absorbed the avant-garde in Paris, where he exhibited with the Fauve, and in Berlin with the expressionists.

By imbibing his 50 CCs of Paris air Munch declared “We want more than a mere photograph of nature. We do not want to paint pretty pictures to be hung on drawing-room walls. We want to create art, or at least lay the foundations of an art, that gives something to humanity. An art that arrests and engages. An art created of one’s innermost heart.”

Tragedy at an early age formed the persona and tormented outlook of the artist. His mother (1868), and sister Johanne Sophie (1877), both died of consumption when he was young. Another sister was mentally ill and he feared inheriting it as well. As a sickly child he was largely home schooled as the family moved to ever cheaper apartments. At his father’s insistence he studied engineering at which he excelled leading to a lifelong interest in science.

University ended when he fell under the influence of the nihilist Hans Jæger, who urged him to paint his own emotional and psychological state. Jæger believed that "a passion to destroy is also a creative passion" and advocated suicide as the ultimate way to freedom.

With his mates Munch drank and brawled to excess. "My ideas developed under the influence of the bohemians or rather under Hans Jæger. Many people have mistakenly claimed that my ideas were formed under the influence of Strindberg and the Germans ... but that is wrong. They had already been formed by then,” he stated.

In Paris, 1889, he absorbed color as a means of emotional expression in Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent Van Gogh. A German colleague observed that "He need not make his way to Tahiti to see and experience the primitive in human nature. He carries his own Tahiti within him."

The bohemian lifestyle caught up with him. In the autumn of 1908, there was a breakdown. As he later wrote, "My condition was verging on madness—it was touch and go." He entered the clinic of Daniel Jacobson. For the next eight months, therapy included diet and "electrification." He returned to Norway in 1909.

This was a turning point and by his mid 40s Munch was successful. He sold some 30,000 prints which made his work accessible and popular. It also meant that he was able to horde his paintings.

The Nazis invaded Norway in 1940. In Berlin in 1937 they mounted the exhibition "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art) of some 600 works removed from German museums. Collectors in Norway bought back 71 of his works but 11 were lost. Munch feared arrest and confiscation of work that filled his house. When he died in 1944 the Nazis staged an elaborate funeral.

When Munch died he donated his estate. Construction of a museum was financed from the profits generated by the Oslo municipal cinemas and opened its doors in 1963 to commemorate what would have been Munch's 100th birthday. Additional works were donated by his sister Inger Munch. In May 2013, the multi-leveled museum moved to its new site on the waterfront, next to the Oslo Opera House. It has been rebranded as Munch-Musett MUNCH.

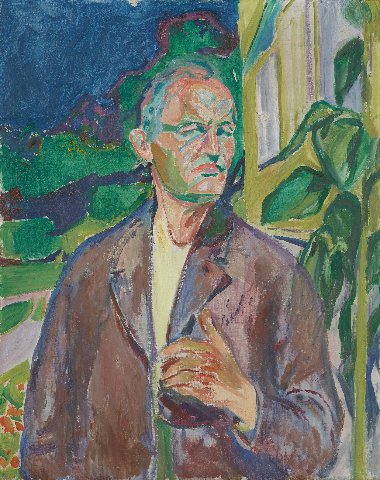

Trembling Earth features seventy-five objects, ranging from brilliantly hued landscapes and three stunning self-portraits, to an extensive selection of his innovative prints and drawings. The exhibition includes more than thirty works from MUNCH’s world-renowned collection, major pieces from other museums in the USA and Europe, and nearly forty paintings, prints, and drawings from private collections, many of which are rarely exhibited.

“This exhibition draws on new research to offer a fresh perspective on Munch’s career,” said Jay A. Clarke, Rothman Family Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Alongside depictions of death, existential torment, and troubled relationships, Munch also created imagery reflecting his knowledge of science, showing his embrace of pantheism, and a deep reverence for nature.” Clarke led the curatorial project for the Clark and began early work on the exhibition when she served as its Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs from 2009–2018.

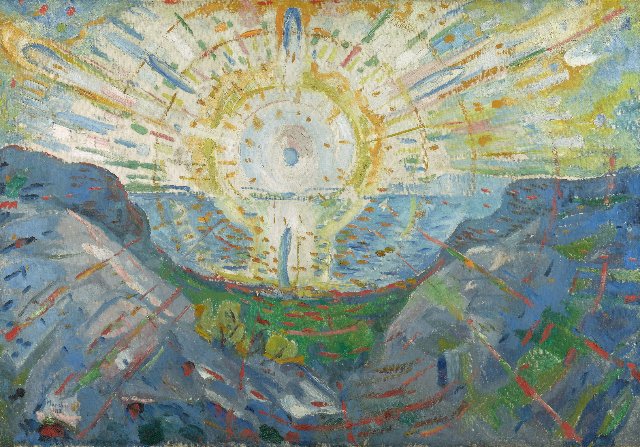

The galleries are organized around themes: In the Forest, Cultivated Landscape, On the Shore, Chosen Places, The Scream of Nature, Storm and Snow, In a Cosmic Cycle, Beneath the Sun. The exhibition shows how Munch used nature to convey human emotions and relationships, celebrate farming practice and garden cultivation, and explore the mysteries of the forest even as his Norwegian homeland faced industrialization.

Munch developed his own pantheistic worldview that connected human biology, plant life, and the solar system. Munch’s was fascinated by humankind’s interaction with the earth and the impact of one on the other.

Ambulating the exhibition evoked the lyrical “Norwegian Wood” of John Lennon. Dominated by pine and evergreen there is an austerity when compared to the lush Tahiti imagery of Gauguin who Munch admired and absorbed. A trained eye, however, will note similarities of the broad flattening of areas and arcing edges containing swaths of paint and color. They are the culmination of “soul paintings” which had started with the influence of Hans Jaeger. While sourced through post impressionism and fauve, the paintings, with a distinctive Nordic austerity feel filtered and deracinated. At times, when the subject inspires, there is a robust, swashbuckling attack on the canvas. At others a thin, chalky, seemingly tentative approach to canvases that appear bare and unfinished.

If we calibrate while taking on the maze of galleries with their distinct themes, we experience the range of the artist. What feels initially like a critical mass of Munch breaks down to sub currents and deviations from true North. Some works are more compelling than others. That’s up to the viewer to decide. Perhaps it’s too much to sort in just one visit.

In The Logger, 1913 and The Yellow Log, 1912, we are confronted by the forest as material. When felled what was a tree in a primeval forest morphs eventually into lumber. Broadly painted with little attention to detail the lumberjack is a worker and everyman. The result of his labor lies in the midst of the woods as a kind of glowing yellow corpse.

Is it anachronistic to read into this a loss of environment? From the current perspective of global warming that’s an instinctive interpretation. Arne Johan Vetlesen evaluates this in the catalogue essay “Munch and Grief over Lost Nature.”

As a child Munch’s father read ghost stories to his children. One feels this spooky other world in the gnarly tangle of The Magic Forest, 1919-25. There is a sketchy indication of a mother and daughter ensnared in this space.

One thinks of the Barbizon painter, Jean-François Millet, in Fertility, 1899-1900. In a tight composition husband and wife are harvesting fruit from a tree. Uniquely, Millet often depicted men and women as equals sharing farm labor. Millet influenced Van Gogh who here echoes through Munch. It is a rare image of bucolic serenity in the exhibition.

Again Munch evokes Millet in The Haymaker, 1917. The artist’s ravishingly fluid brush strokes are entirely drained of their impact in the flattened, dull, catalogue reproduction. Similarly, one does not get the full dramatic impact of his rendering of horses pulling the plow. On the walls these are visceral and ravishing works.

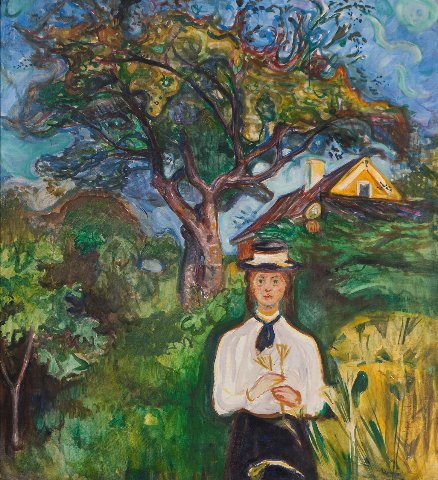

Young Woman Under the Apple Tree, 1904, represents the best of Munch. There is the entangled mass of branches over her and to the right a slice of the roof of a farm house. In a frontal pose she gazes at us with haunted, hypnotic circles for eyes. With her little hat she is the very model of a modern Major-General, or, in this case farm girl in her Sunday best. What a charming picture.

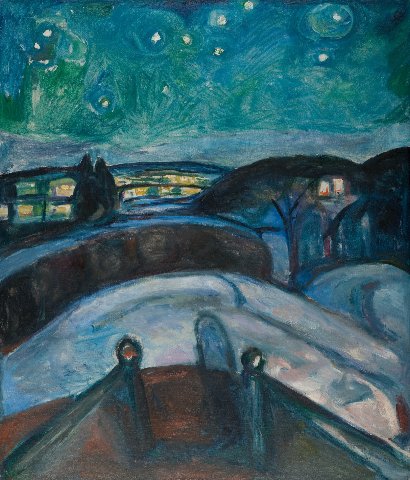

Summer Night by the Beach, 1902-03 is a haunting “Clair de Lune.” His nocturnes are sublime and the painting for once is fully resolved with virtuoso brush work. He has a trick of rendering moon and reflections as abstracted lozenge shapes. We see this repeated in a number of paintings and prints including Summer Night’s Dream, The Voice, 1893. from the Museum of Fine Arts.

Two Human Beings, The Lonely Ones, 1899, is represented by several impressions of this woodblock print. In a very Nordic romance we encounter the couple from the rear. They are separated physically but united in contemplating nature. With a jigsaw the artist separated the block into several elements. These he inked separately and then joined for an endless spectrum of variations.

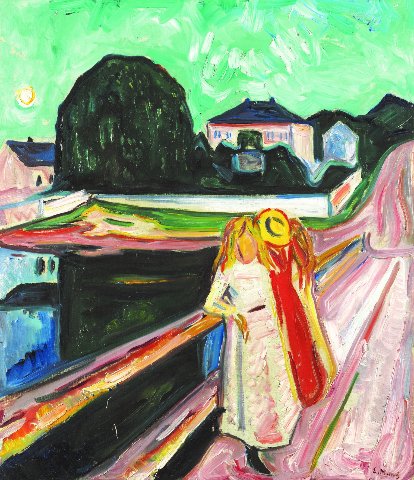

There are subjects which he approached a number of times with paintings and prints. It is intriguing to see all the variations of Girls on the Bridge, 1918 to 1903.

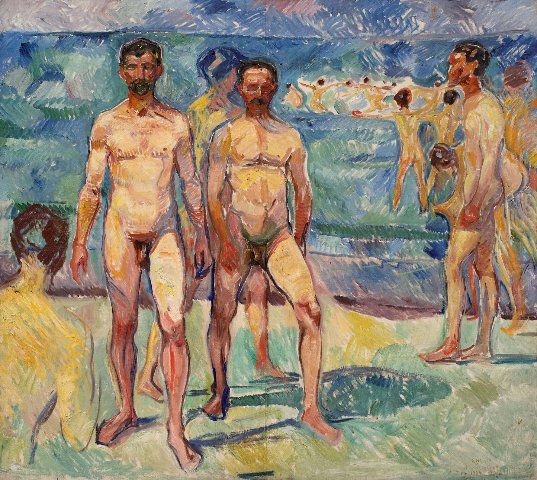

As a Scandinavian, Munch embraced vigorous nude bathing and we would assume saunas. The large painting, Bathing Men, 1907-1908 was a delightful shock and surprise. The nude is a norm for Munch but here the males are devoid of sexual tension. There is a casual naturalism to the trim, athletic men who celebrate nature.

In a catalogue photo we view the artist working outdoors on the painting. We learned that he was prone to letting certain works weather outside the studio.

There is a stylistic device of several, abstracted, horizontal bands that sweep across the background of Bathing Men. The curator, Jay A. Clarke, pointed to an “abstract” canvas which may have been a study for this approach. She asked a rhetorical question as to what contemporary artist was influenced by this pattern? There was a silence, then I answered “Jasper Johns” which proved to be the right answer.

I have often contemplated the meaning of The Storm, 1893 from the Museum of Modern Art. At the edge of the shore there is a cluster of sketchily rendered figures with a woman in white to the right of them. They have hands over their ears in the manner of The Scream. Behind them is a house with windows illuminated by interior light. Clarke unlocked the mystery explaining that they are reacting to a capsized vessel.

The gallery designated as In a Cosmic Cycle proved to be most intriguing with a display of Munch’s theory and philosophy that I was unaware of. The cosmology is intense and difficult to understand. The MUNCH curator, Trine Otte Bak Nielsen, discussed his theories. I followed up by reading her chapter “Even in the Hardest Stone the Flame of Life Blazes.”

Those concepts are represented by the most challenging images in the exhibition. They are intriguing but remain elusive. I will reread her essay before the next visit. The Funeral March, 1897, and The Human Mountain, 1909-10 depict corpses piled up one on the other reaching to the sky as a spiritual quest.

There are several graphic works depicting buried corpses that are nurturing figures above them. A notion is that death is just another beginning. In “Even the Stone’s Hard Mass is Alive” conveys that nothing in nature is inert.

To get the most out of this exhibition, from its visual power to psyco/ philosophical contemplation, will require more then one visit. Anticipate being enchanted, flummoxed, and intrigued.

Captions

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1895, lithograph on paper. Private collection, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait in Front of the House Wall, 1926, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00318, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet / Ove Kvavik

MUNCH on the waterfront, Oslo.

Tone Hansen director of MUNCH, Giuliano photo.

Curator Jay A. Clarke, Giuiano photo

Curator Trine Otte Bak Nielsen, Giuliano photo.

Edvard Munch, Girls on the Pier, c. 1904, oil on canvas. Kimbell Art Museum, AP 1966.06, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edvard Munch, The Girls on the Bridge, 1902, oil on canvas. Private collection, © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edvard Munch, The Sun, 1912, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00822, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet / Ove Kvavik

Edvard Munch, Girl Under Apple Tree, 1904, oil on canvas. Carnegie Museum of Art, acquired through the generosity of Mrs. Alan M. Scaife and family, 65.16, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

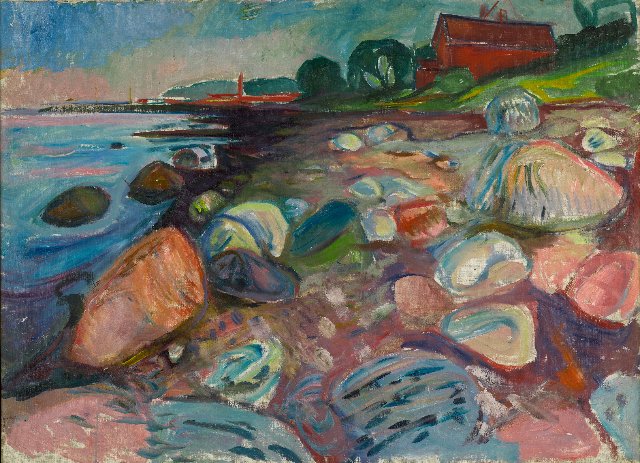

Edvard Munch, Beach, 1904, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00771, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet / Juri Kobayashi

Edvard Munch, The Haymaker, 1917, oil on canvas. Munchmuseet, MM.M.00387, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Munchmuseet / Halvor Bjørngård

Edvard Munch, Summer Night by the Beach, 1902–03, oil on canvas. Private collection, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edvard Munch, Summer Night's Dream (The Voice), 1893, oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund, 59.301, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings. The Lonely Ones, 1899, color woodcut on paper. Private collection, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Print variations, Giuliano photo.

Edvard Munch, Bathing Men, 1907–08, oil on canvas. Finnish National Gallery, Ateneum Art Museum + Collection purchase by the Antell deputation, A II 908 © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Pakarinen

Edvard Munch, Fertility, 1899–1900, oil on canvas. Canica Art Collection, Oslo, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York