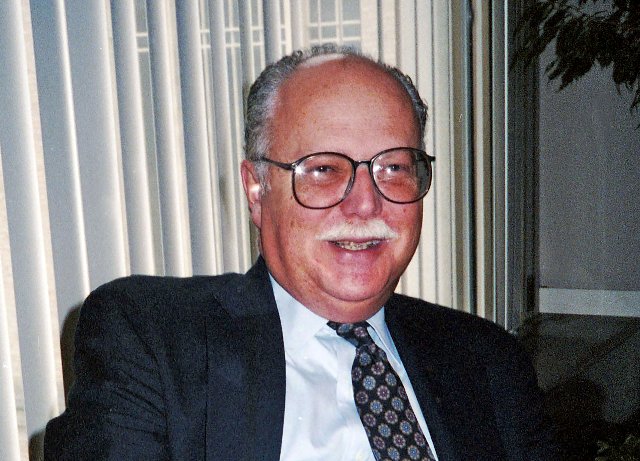

Alan Shestack Two

In 1992 the MFA Had an Annual Deficit of $3 Million

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 15, 2020

When I interviewed Alan Shestack in 1992 he had been MFA director for five years. It was a time of economic downturn and the museum faced an annual deficit of $3 million. We discussed ways in which the museum might meet this challenge including launching a relationship with a museum in Nagoya, Japan which it helped to launch and program. He spoke adamantly that selling works to cover costs violated the mission and covenant of museums and their donors.

In order to survive Brockton's Fuller Museum of Art deaccessioned art. As did the Rose Art Museum. His position at the time seemed harsh. It proved to be prophetic when recently the Berkshire Museum opted to sell 40 works, including two by Norman Rockwell, for renovation and its New Vision. They won a court battle to proceed with the sale which had been widely opposed. Now that museums are closed and cash strapped because of Covid-19 that precedent, and Shestack's adamant reasoning against it, becomes ever more relevant.

Charles Giuliano When we first talked you described jumping onto a fast-moving express train. Through a time of economic downturn there has been a slower pace. The negotiations with Nagoya, Japan have been a part of creative ways to generate more revenue for the museum. Through his relationship with Japan did Jan Fontein have any role in that?

Alan Shestack None whatsoever. He had been in and out of the country. He had nothing to do with it. What we are doing with Nagoya is very different from the satellite museums of the Guggenheim.

In those cases, they are administered by the central museum. The city of Nagoya is building a museum. We are a consultant to that project. When the museum exists, we will provide it with exhibitions. It will be a Nagoya Museum it will not be our museum. They are appointing a director who will be working with me and the architect.

The Guggenheim Bilbao will be staffed with people sent from New York. That will not be the case with us. Nagoya is a wealthy, prosperous city which felt the need for more cultural opportunity. We are helping them to do what they want to do for themselves. We are not going to run that museum.

CG How did the project come about?

AS We were approached by an emissary from the Nagoya Chamber of Commerce. That was about a year ago in early 1991. They asked if we had interest in helping them. In Japan we are considered as the ne plus ultra of museums mostly because of our Japanese holdings. They asked if we were interested in assisting them in forming a museum. That led to me going there for two days of meetings. I wanted to know more of the scale they were talking about. What kind of participation were they looking for on our part? I wanted to know what they wanted from us. What was in it for us?

This marriage occurred for two good reasons. Nagoya is perhaps the only large industrial city that does not already have an abundance of museums. As you know our museum has basements full of stuff that we don’t show. The combination proved to be unbeatable. That couldn’t happen with an American museum that didn’t have great reserve collections. Nor could it happen in many other Japanese cities. It is a city of four million in its metropolitan region. It has headquarters of Toyota and Yamaha. The city is fully employed. The major corporations got behind the Chamber of Commerce. The prefecture in which Nagoya is located and the region were all eager to help. The city decided that they would build the museum. Everyone came together.

CG They made you an offer you could not refuse.

AS Not at first. It took a while to negotiate what it would take to make it happen. The first thing I said was that there could be nothing out of pocket for us. We were not in a position to subsidize a museum in Japan. We needed to be reimbursed for the effort we would make. It would take additional staffing to make it happen. The already stretched staff of the museum couldn’t be expected to do it. They agreed to cover between five to seven salaries. We are still negotiating that. That would entail a registrar as well as exhibition planners and so forth.

We discussed a signing bonus for the project which we are still negotiating so I can’t give you those numbers. Though we’re not out of the woods this project will go a long way toward a balanced budget. It’s going to be substantial help. But this is not going to solve all of our problems.

CG What are those problems?

AS We have a structural deficit of $3 million a year. We have been working hard to cut costs and enhance revenue. Those are the two things you do when there is a financial crunch. Against general trends in New England our attendance is up 18% over last year.

To be crass, I’ve been pressing our retail people. They have increased our mailing list also bucking trends. We are looking at restructuring staff which could result in annual savings. We cut back 46 and let go 26 positions. We have a staff of about 500. That’s about 10%, which compared to Detroit and Brooklyn, we have been riding high. We have yet to close galleries as has the Metropolitan Museum.

CG European museums have always done that.

AS They have in response to levels of government support. We have not cut programming.

CG In the past there have been times when galleries were not staffed.

AS That’s something we might have to look at. That has not occurred in light of the current financial troubles we have been facing.

(In 1992 A New York Times/CBS News poll of 1,530 Americans, taken between April 20 and 23, found that many people were unhappy about the economy. In the poll, 24 percent of respondents said the economy was in very good or fairly good condition, while 40 percent said it was fairly bad and 34 percent said it was very bad. Eighteen percent said the economy was getting better, 31 percent said it was getting worse, and 50 percent said it remained the same.)

CG Had Nagoya not come along at an opportune time what were you facing? What is the role of state and federal funding?

AS As you know, the museum has never had substantial state funding. We’d gone from $60,000 to $8,000 a year. It’s virtually pennies.

CG What can you do with $8,000?

AS That pays for one children’s program.

We have been very aggressive in seeking to make up for that reduced state money and have been very successful. Not one of our education programs has been terminated. But it’s through private donations from several sources. I just sent a thank you letter to a family which has funded a program for a year. We’re out there hustling for money. We don’t want to see education programs disappear because state money has dried up.

There have been a large number of expenses. For example, just covering health benefits for the staff. That cost has quadrupled in the past five years. Those bills go up by hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. That’s one factor.

We have had some extraordinary expenses in our school. The HVAC system was not functioning properly. It had to be completely redone at a cost of several million dollars. We had to make life tolerable and get all the toxic fumes out. It required an enormous retrofit job.

You have a staff of 500 with a budget of $15 million. That’s an average of $30,000 a year. And when you give a 5% pay increase, that adds $600,000 to your operating budget. In a year when you don’t necessarily have additional attendance. That compounds and how are you going to cover that? Museums and all cultural institutions are constantly in that position of having their costs compound while income increases arithmetically.

I’m happy to say that giving to the museum has not fallen off. It is as it was before and membership is actually up over what it was last year. We have taken on additional debt service. We built our garage on borrowed money. It was not part of our prior budget and now we have debt service. That has suddenly been added onto our operating budget. We have debt service on the bond issued for the West Wing. People say your grandchildren will have to pay for it. In some regards I’m the grandchildren. Debts are coming due and we are having to pay for them.

The positive of this is that the board recognizes that we have debts and sees the need to build a capital base. There will be a capital campaign starting probably some time this year.

CG What is the endowment?

AS $143 million. That’s about half of what it should be.

CG How does that compare to other major museums?

AS The National Gallery has no endowment but gets $45 million a year from Uncle Sam. That’s the equivalent of having $1 billion endowment which you’re paying for through taxes. The Met endowment is something like $300 million but I’m not sure. The Cleveland Museum has $300 million for a museum a third the size of this one. The difference between us the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Philadelphia Museum, is that they are handsomely supported by their cities. A third of their operating budgets come from their cities. We get nothing. We are at a tremendous disadvantage. We are one of the very few, major, urban art museums in the country that get no support from their city.

CG Unlike the Met you are not on city land.

AS We are a private museum. That’s a detriment to us. There’s no question about it that’s just an historical fact. The reasons for it are complicated and not worth going into. That’s a problem and we start with a tremendous disadvantage compared to the Art Institute of Chicago. Our budget is less than half of theirs. They’re well over $60 million a year and we are not up to even $30 million. We manage to be a world class museum on a budget that’s half of what it should be. It’s amazing what we accomplish.

The guards at the Met are paid by the city as are the utility bills. We have 120 guards. If they were all paid for by somebody else, and we didn’t have to pay for heat, light and air conditioning, we could have a balanced budget without any money from Nagoya.

CG At the National Gallery the guards are civil servants.

AS I think we’re finding some creative ways out of our hole. Nagoya is not the only money we’re raising in Japan. We are packaging and sending to Japan other exhibitions. We have one on right now of screens from the Fenollosa collection. It’s in Tokyo and will be in Hiroshima in a week or two. We are sending a French impressionism show next year that does not yet have a title. It’s about 70 works.

CG The MFA has the greatest Asian collection in the world. Is that what Japan wants to see? Will you send a national treasure like “Burning of the Sanjo Palace?”

AS We will not let what we send to Nagoya reduce the strength of what we display here in any way. What we send will mostly be from the storage collection.

(That was true for Shestack but loans, including major French impressionist and post-impressionist works, were frequently packaged in loan shows under Malcolm Rogers. So much so, that there were media protests including former Boston Globe art critic Sebastian Smee who wrote in part, “However, the MFA, eager to raise revenues, is also renting out many of its most prized works of European and American art to for-profit enterprises. A total of 26 paintings, including the marquee “Dance at Bougival” and “Madame Roulin,” have been sent to exhibitions in Italy organized by a private company called Linea d’Ombra, for a large, undisclosed fee.

“The combined loans and rentals have resulted in what Malcolm Rogers, the MFA’s director, readily admits is a “traffic jam” of missing masterpieces. “We admit there is some crowding [on the list of masterpieces sent away],” Rogers said in an interview with the Globe. “Everything has come together at once.”

We experienced that first hand when visiting the Frist Museum in Nashville. The theme of the show sent from Boston was Japanese influences on French impressionism. While mostly consisting of reserve collections and Japanese prints, it was highlighted by masterpieces including van Gogh’s iconic portrait of “Madam Roulin.” The Frist has no permanent collection and programs loan shows. There is a circuit of such institutions which do not provide the quid pro quo that is the norm for museum exchanges.)

The Nagoya committee that will be working with us is yet to be appointed. We will be dealing with museum professionals in Japan. They will work with us on the specifications for the building and begin to work on the programming.

From the initial talks with powers that be, they want a mixed diet with Egyptian and classical, Greek and Roman, European painting, prints and drawings. I asked how about photography shows? They responded if they’re good enough. I thought of sending the Ansel Adams photographs from the Lane Collection. There seems to be no restriction. They don’t want contemporary. They are less interested in Japanese art as there is already a Japanese art museum in Nagoya. It’s a quite good museum.

(The Tokugawa Art Museum is a private art museum, located on the former zone Shimoyashiki compound in Nagoya. Its collection contains more than 12,000 items, including swords, armor, Noh costumes and masks, lacquer furniture, Chinese and Japanese ceramics, calligraphy, and paintings from the Chinese Song and Yuan dynasties.)

CG The Japanese are notable as tough negotiators. Will they insist on borrowing Asiatic masterpieces?

AS It is unlikely that we will send one of our five most notable works.

CG Jan Fontein sent “Burning of the Sanjo Palace” but told me that he had overcome an estate restriction against loans.

AS That was an exceptional circumstance for a temporary exhibition that required board approval. That was at most a few weeks. We are talking about a general exhibition program with a great variety of works. They are not interested in contemporary art but when the program is up and running, five or so years from now, we might say ‘how about this?’

It’s also possible, but not likely, that shows that we organize for ourselves might also travel there. But that’s not what they’re looking for. They want representative sampling and exhibitions that come out of our collections. We have promised that they can be there as long as six months. Actually, five months with a one-month turnover. We would send two exhibitions a year.

We will fill two spaces each approximately 5,000 square feet. One would be more or less permanent. It could be Art of the Ancient World. That would include Egyptian, Greek and Roman. We could put together a hundred objects that would remain on view for up to five years. That would be plugged into the curriculum of their schools. That’s enough lead time to really use those collections.

That would be very important to them because there are no Japanese museums that own Western antiquities. This is an opportunity for them to draw on the rich reserves in our collection. They would have exhibitions that do not exist anywhere else in Japan. There are some small museums that have three Egyptian objects. They were collected in the last decade. Of course, it’s too late. You don’t start in 1992 to collect that material.

We haven’t gotten into programming yet but they want to see work from virtually every department in the museum. We will start with Classical and Egyptian for five years. They want to take other shows from other institutions. They want in on Leonard da Vinci. That’s their business.

CG Have you enjoyed a lot of sushi?

AS In the past couple of years I’ve been to Japan five times. I have certainly enjoyed many fine Japanese meals. It’s interesting that the Japanese enjoy diverse food and some of the finest restaurants are French or Italian. You often have a great French meal rather than a Japanese one. I may imagine that some of those meals cost more than $100 per person. (both laughing) I have been well entertained in Japan and not just in Nagoya.

Directors of this museum are celebrities in Japan which I didn’t know until I went there. They think of the MFA as the most important cultural institution in America. Again, that’s because of our holdings in Asiatic art.

It has taken a year to negotiate a contract because it takes time to develop rapport. We have now reached that point. By now neither side will back away although we do not yet have a contract. We have reached the point of shaking hands and moving forward. Now we need to iron out some of the details.

CG Given the depth of the collection what is the possibility for the museum to develop satellite operations. When the Evans Wing of Painting was closed for renovation, for example, Ken Moffett was curator of an MFA gallery in Quincy Market. What about MFA related retail operations?

(Five years after we spoke the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum opened on 18 October 1997. The stunning structure designed by Frank Gehry was an immediate success. Then Guggenheim director, Tom Krens, developed other global projects with varying degrees of success. Prior to the Guggenheim, while at Williams College, Krens launched what became MASS MoCA. The initial plan was to warehouse the mimimalism collection of Count Giuseppe Panza di Buomo and other private collections. The New York museum also manages the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice. Perry Rathbone attempted to lure her collection to the MFA. One who was in the room told me, off the record, that she had an unfortunate encounter with a representative of the MFA.)

AS The Quincy Market venture lost money. It was limited because the elevators were small. The venture was a looser because of money. As to retail, virtually every museum in the country is doing this. The Met maintains eleven shops. There’s a museum shop in Columbus Ohio in a shopping mall. We’re looking into that.

CG What about satellite exhibitions with corporations?

AS We have not looked into that. The climate if not right now to find a corporate sponsor. Not when they are laying off because of the recession.

(There was a Guggenheim satellite in Las Vegas which has since closed. Steve Wynn had a small museum in his hotel that included a Vermeer and other choice works from his collection. Despite wealth and tourism Las Vegas does not have a major museum.)

CG All museums great and small are exploring ways to monetize their collections. That includes deaccessioning. The Fuller Art Museum (Brockton) sold a dozen works at auction. The Rose Art Museum has sold works not within their core mandate. How do you feel about museums in dire financial straits selling works from their collections?

(Then director Katherine Graboys was sanctioned for selling works for operating expenses. She died young of cancer as did, ironically, Jennifer Atkinson who succeed her. The museum changed from Brockton Art Museum to Fuller Museum of Art. It offered diverse contemporary programming including The Brockton Triennial. There were major exhibitions of William Rimmer, Henry Schwartz, and Hyman Bloom. To make itself more focused and a destination as The Fuller Craft Museum. Grayboys made a drastic and controversial move but accordingly, while reconfigured, the museum continues to exist.)

AS I am opposed to deaccessioning for any reason other than to upgrade the collection. To sell works from the bottom of the collection, that we would never show, to upgrade to better works is done all the time. Since I have been here, we have sold at least a thousand works. A lot of what we sold was just junk. That material was acquired a hundred years ago when we inherited the entire contents of people’s homes. That included rugs and ash trays. In terms of objects of any value we have sold some silver and minor paintings to buy major ones.

CG What about Pollock’s “Troubled Queen?” The museum deaccessioned two Renoirs and a Monet.

AS That was before my time. I had nothing to do with it so I do not wish to comment. I’m telling you what we do now. I’m telling you what my policy is. You start down a slippery slope when you do what Brandeis did.

CG You can say that from the position of running a great institution when talking about the survival of a smaller and more vulnerable one. I spoke with Carl Belz (Rose Art Museum director) a couple of weeks ago and they were cutting the staff by half. With reduction of programming they are ceasing to function. I understand the concept for major museums to deaccession to upgrade collections but there are now museums like the Rose, Danforth and Brockton facing desperate situations. Their very existence is in jeopardy.

AS What is their purpose for being? Their raison d’etre? The purpose is to collect, preserve and display works of art. If it cannot do so for lack of money it is better to go out of business and distribute the works to other 501c3 institutions that can take care of them. It is better to go out of business than to deny your birthright.

CG Doesn’t that situation describe a number of institutions in America at this time?

AS It’s an easy road to follow. What does a symphony orchestra do when it’s in trouble? It can’t sell some violins and a tuba. They somehow manage to survive through more aggressive fundraising, appealing to the community they live in for that support. They don’t have access to things they can sell.

A museum’s primary mission is very clear. It doesn’t matter if it’s big or small. It’s to collect, preserve, exhibit, and interpret works of art. The minute you start raiding the collection and thinking of it as a commodity, that can be utilized at the moment for expedient reasons, for solving your problems, rather than having your board working on more creative solutions, working with Nagoya, Japan or whatever else you decide to do.

This museum has been in trouble many times. On one occasion the decision about what to do was about going into the retail business. To become a marketer. That’s a solution we’re still benefiting from. Some museums package and market exhibitions that tour around. That’s another thing that you can do.

Some museums go out and find an angel who says, I love your museum enough to underwrite what you do. Cultural institutions in this country have never made it on their own. They have always depended on charitable institutions. If you don’t get that charitable support you don’t exist.

That five or six dollars per visitor at the gate adds up to $3 million a year. Half of our visitors are members who don’t pay for admission. That $3 million a year at the gate is just 10% of our budget. You are never going to make it on admissions.

As a colleague described it to me, when a museum sells its works to save itself, it’s like a Siberian peasant. He’s cold and starts to take his house apart and throwing it on the fire. He may have kept warm for a couple of weeks but in the end, he doesn’t have a house. That’s what deaccessioning for cash flow is like.

CG I agree that it’s a Sophie’s Choice but these are not normal times. I’m the one you may recall who made a case about deaccessions for the Pollock. The issue was swapping French impressionism for American modernism.

AS I don’t agree with that. If I had been director at the time that would not have happened. I don’t believe in that and think it’s a mistake. Regarding the original donors if you buy art using their money, to buy in a field they might not have admired, to put their name to a label, is a betrayal of trust.

CG It was apples and oranges in this case three French impressionist works for one American modern painting.

AS Once you have depth in particular artists (Renoir and Monet) you become a resource for their work. It’s a mistake to reduce the critical mass of those artists in the collection.

(From an MFA press release, “Beginning in April, (2020) the museum will display its entire collection of Claude Monet oil paintings — all 35 of them, which is “among the largest holdings of the artist’s work outside France.” Six Monet paintings on loan from private collections will round out the exhibition, bringing the grand total of works to 41. Titled “Monet and Boston: Lasting Impression,” the exhibition will highlight the city’s and the museum’s commitment to the artist.” That’s minus the Monet painting deaccessioned for the Pollock.)

It was a terrible mistake. I disagree with that entirely.

(The issue of deaccessioning to pay for operating expenses has resurfaced since our discussion in 1992. I agree with Shestack’s arguments that seemed harsh at the time. In 2009 Yehuda Reinharz, then president of Brandeis University, attempted to sell the collection of the Rose Art Museum and close the museum. It was evaluated at $300 million at the time. Protests led to his resignation and reorganization of the museum. In 2017, as part of A New Vision Van Shields, then director of the Berkshire Museum, presided over the deaccession of 40 works including two given to the museum by Norman Rocwkell. The sale, which was fought in court, yielded less than an estimated $60 million. The money is going to renovation and endowment and not for acquisition funds. Now, with a pandemic, museums closed, and funding harder to find with economic decline, many museums boards are contemplating the path opened by lawyers for the Berkshire Museum.)

I was a director of a university museum at Yale for many years. You set priorities and for me it was the collections. I would cut back exhibitions, I would reduce staff, I would do a lot of things before I would sell works from the collection to cover costs. Selling works is the last thing, not the first thing you do when facing financial crisis. It diminishes the cultural patrimony of the community. It often leads to the works leaving the country. In most cases it’s a betrayal of trust to the original owners. It sets a precedent and example for boards of other institutions to put pressure on their directors and curators to diminish their collections to meet the needs of the moment.

CG On another tack, I was surprised that you opted not to return a stolen Egyptian pectoral that was acquired by the museum. Why was that?

AS I was following the advice of several well-paid lawyers.

CG I had thought of you as an individual of impeccable ethics.

AS I try to be but this is the story. I acknowledged to Lafayette College that the pectoral had been stolen from them.

(It is a fascinating story that includes theft and even the unsolved murder of a 64-year-old librarian. She was stabbed multiple times. The 3,600-year-old pectoral, a breastplate from a royal Egyptian sarcophagus, was stolen from Lafayette College in the late 1970s. In 1858 Roxbury, Mass., civil engineer George Alfred Stone acquired the piece in Egypt. The breastplate as well as papyrus and several other artifacts were from a royal tomb in Thebes. Fearing a curse, Stone's widow in 1873 sold the objects to Lafayette for $425. The breastplate was on display at the college from 1873 to 1968, when an art expert advised the college to protect it from deterioration. It was then placed in the library's rare book vault. It is alleged to have been stolen by reference librarian Robert G. Gennett. Records of the Egyptian objects were destroyed. The pectoral went on the block at Sotheby's on Dec. 11, 1980. It did not draw the minimum $110,000 the seller required, and later that month was transferred to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for $165,000 in a sale arranged by Sotheby's. The college didn't discover the pectoral was stolen until late 1987.)

When you have something stolen and you don’t report it for ten years, when you’re covering up murders and all kind of things by not reporting to the police. The theft was annouced ten years later when a new president comes to the university.

When it was first discovered that what we owned, purchased from Sotheby’s, which had put it on the cover of their auction catalog, nobody denied that this transaction had taken place. Regarding provenance, there was no mention of it and we had no idea where it came from. Prior to 1981, there was no notion of where it came from. We did a thorough search prior to the acquisition.

CG It went to the Met for cleaning and restoration which is how the connection to Lafayette surfaced.

AS We were led to believe that Lafayette had deaccessioned it. That was the decision of the people at the Met. We were not to mention Lafayette as they would be embarrassed for having deaccessioned it. There were all kinds of funny things involved.

When it was taken from the vault of the rare books collection of the college library one could argue that it had minimal value. It was suspected to be a forgery and when it was consigned to Sotheby’s it was bad mouthed in the trade. When it came up at auction there was not one buyer willing to bid on the reserve price for the object.

Kelly Simpson (MFA curator of Egyptian Art) had the intelligence and eye to see that under all the grime and grit it might be something. He believed in it and came back here and persuaded Jan (Fontein) to buy it. We went to Sotheby’s which acted as middle man with the consigner, an antiques dealer in Pennsylvania, and the museum which acquired it. At that point it was said to be worth $150,000 (actually $165,000 with fees). It then came here and was worked on for one year. It was studied intensively and put on view in our collection.

(The pectoral is from Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, Dynasty 13-17, 1783-1550 B.C. It is composed of baseplates made of hammered silver sheet, with soldered and gilded silver cloisons (partitions) inlaid with carnelian and glass. The object was fit for a king. It takes the form of a vulture with outstretched wings representing the tutelary goddess of Upper Egypt, Nekhbet, grasping coils of rope, a symbol of eternity. To the left of the vulture's body is a rearing cobra. She is Wadjyt, the goddess of Lower Egypt. Together, they form a pair referred to as the "two ladies," guardian deities of the king. The pectoral was made as a piece of funerary equipment rather than as jewelry to be worn in life.)

It was published four times and became a rather famous piece. We greatly enhanced its value by virtue of the fact that we accepted it. We validated its authenticity. We did the scientific studies that proved its authenticity. We restored and published it.

In the law, an institution or new owner of stolen property, who enhances its value, is entitled to that enhanced value if it goes back to the original owner. Some kind of accommodation has to be reached between the original owner and the new owner. If in fact the object is worth five times as much now because of the very activities of the new owner.

When I learned of the theft, I made an immediate plan to meet with the president of Lafayette college. We sought to reach an out of court settlement. We have been negotiating and are now very close. I offered him cash immediately for title to the piece. It’s now been six to eight months.

We came a long way but couldn’t decide on money so we have just gone to mediation. That report has just arrived and I’m not at liberty to discuss it. I have been willing to pay a certain amount of cash from the outset and they have rejected it. I find the mediator’s report compelling. I’m willing to go along with it if they are. The piece will stay here and we’ll write a check to Lafayette.

CG The president of the college (Robert Rotberg) told the media that he wanted the piece returned. You are saying that he wants a check.

AS It would be interesting for me to ask him why he wants it back? He’s a Rhodes Scholar and a very smart man.

CG You seem like a straight shooter, but now and then you surprise me, like this pursuit of the stolen pectoral.

AS Well then, you tell me. If you have had something for ten years and somebody came along and said “Hey, that’s mine.” If you went to an attorney and said “What should I do?” Then were told this is very complex law. The statute of limitations have run out. Then try to find out why they didn’t report the theft. You hire detectives and they find all kinds of funny reasons why it wasn’t reported. If you don’t report the theft it is no longer your property by law. It’s not a simple case.

Mr. Rotberg and I get along fine until we talk about money. One joke he made was “Which of us gets the TV rights to this?”

CG It’s got all the elements to make a great novel then movie. Will Robert Redford play you? (both laughing)

AS If you were director of a museum and someone came along and claimed one of your objects would you just say, sure, here it is?

CG Museums return things. Jan Fontein spoke with me about returning a statue of Shiva. The MFA was sued by Italy for the return of the (alleged) Raphael portrait (of Eleanora Gonzaga). We see more and more examples of this with museums.

AS This is a gray issue. It’s not black and white. If a foreign government can show me that a work was stolen from that country, and they can prove it, I don’t hesitate for a second to return the work. This is a case where the previous owners of that object did nothing for a hundred years. Since the 19th century. They never showed it. They never found out what they had and let it become tarnished. It became filthy. When it was taken, they didn’t mention it to the press. I have an obligation to the institution.

CG On another subject what is the acquisition fund for annual purchase of contemporary art?

AS About $50,000. Why, do you want to contribute to the fund? (both laugh) I’ve been looking around for money and it hasn’t been flowing in. We’ve had some very nice support from the Beal family. We have occasional gifts of $5,000 to $10,000. For our capital campaign we are not allowing any other department to raise money for acquisitions. But we are making an exception for contemporary. We welcome gifts for the acquisition of contemporary art.

CG This was the year when there was changes in the tax law for deductions for gifts to museums of works of art. How did that impact the museum?

AS It was a good year for us. There was no avalanche but it was a good year. In the painting department, for example, we got a Copley, a Heade, and a very important Sargent. The window of opportunity because of the tax law encouraged donations. In musical instruments we got a harpsichord which may be the most important object in our musical instruments collection. Enormous collections of American silver were given.

CG What would you say is the worth of the collections?

AS I don’t run around with an adding machine so I have no way of knowing.

CG Are we talking in terms of billions?

AS Yes, but, how many billions is impossible to say.

CG I am just observing that the museum holds billions in assets but is cash poor. By contrast the Getty has enormous assets but lacks depth in its collections. There is an irony here to consider.

AS It’s a terrible irony but shouldn’t lead us to the perverse decision that the collections should somehow fuel the institution.

CG The discussion is how to make the equity of collections help to fund and sustain the institution. The Nagoya arrangement is one example of how that might work. Fees for loan shows is another. Moving forward it is likely that museums will seek more such creative options. It will be particularly difficult for small and mid-level museums, without deep collections, to survive times of economic downturn.

You are the expert in the field. I am at best a messenger, as I speak with all levels of museum directors and curators and hear their challenges. I am trying to form a coherent view of how institutions survive and move forward.

The Institute of Contemporary Art, for example has a policy not to collect. That means that all of its money has gone into programming so there is no equity in terms of a collection that has increased in value.

AS They have no place to put it.

CG You have been able to generate exhibitions based on collections. Ultimately that has saved money in terms of expensive loans and insurance.

AS There’s nothing wrong with that. You seem to be saying that I should be more sympathetic to smaller institutions with fewer resources to deaccession to cover their costs. I have trustees who would agree with you. There are fewer and fewer who take my position.

Last year we managed to raise $600,000 for Trevor (Fairbrother’s) contemporary art exhibition program. That money came from foundations, private individuals, Uncle Sam, small grants. He put together a pretty damn good year. We had a major Robert Wilson show, Brice Marden, a body show. It was a pretty lively program. We begged and cajoled with people who care about contemporary art. We put the money toward those shows.

We could have taken the money and bought one major work or art. Or could have allowed Trevor to purchase six works for $100,000 each. The program right now is more important to us than adding to the collection. I asked Trevor, because I knew I would be seeing you, how many works of art were acquired by his department? He said that there were 35 acquisitions in the past six months. That’s separate from buying prints and photographs.

Considering the financial state of things our contemporary program is doing very well. I wouldn’t want to trade any work of art to solidify that program.

To come back to your question with permanent collection and loan shows we’re mixing them up. We’re coming out of a very tough year. We are doing somewhat more, out of the basement shows, but have some great shows coming up including “The Lure of Italy” which Ted Stebbins is curating and Peter Sutton is doing “The Age of Rubens.” We’re trying to balance things.