Stoppard's Translation of Heroes by Sibleyras

Wordy Absurdity at Shakespeare & Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 15, 2013

Heroes

By Gérald Sibleyras (2003 French play Le Vent Des Peupliers)

A 2005 translation into English and adaptation by Tom Stoppard

Directed by Kevin G. Coleman

Set Designer, Patrick Brennan; Costume Designer, Esther Van Eek; Lighting Designer, James W. Bilnoski; Sound Designer, Michael Pfeiffer; Stage Manager, Fran Rubenstein

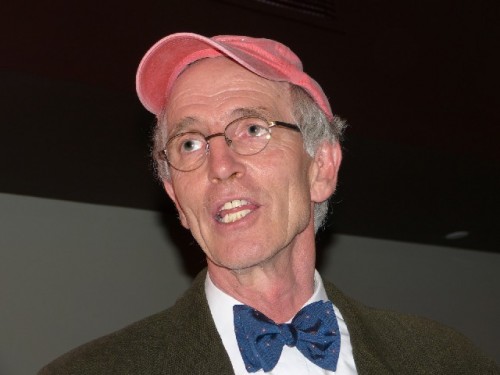

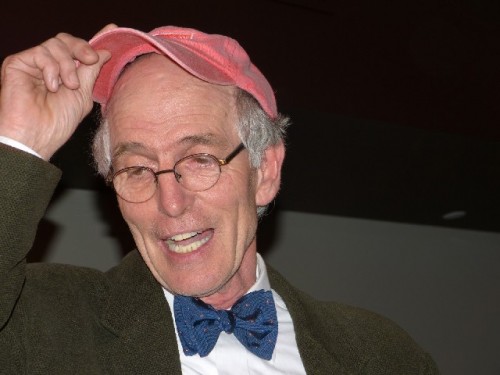

Cast: Jonathan Epstein (Gustave), Malcolm Ingram (Phillipe), Robert Lohbauer (Henri)

Shakespeare & Company

Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre

June 13 to September 1, 2013

The wordy irony and ennui of three military pensioners in a French hospital and retirement home in Heroes the French play by Gérald Sibleyras, translated and adapted by Tom Stoppard, will recall aspects of theatre of the absurd and the stasis of Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett.

Compared with the bare bones Master Class, with which this play will alternate, it has a quite elaborate set by Patrick Brennan. There were opening night quips that it resembles the nearby Mount which was the initial home of the company.

Like the characters in Godot three former officers, Jonathan Epstein (Gustave), Malcolm Ingram (Phillipe), and Robert Lohbauer (Henri), seemingly are suspended in time and space. The incremental passage of days is filled with endless chatter, the pratfall/ blackouts of Phillipe, and vague fantasies of excursions that range from a picnic, suggested by Henri, to a military scaled defense of the terrace by Phillipe, or an escape to a stand of poplar trees (Gustave) and beyond to Indochina.

Actually, there are four characters; if we include a life size statue of a greyhound. No, make that five, as in this production the scowling and autocratic Sister Madeleine, makes the most of occasional appearances with no lines. Phillipe has a delusion that she bumps off one of two individuals with the same birthday. As she is only capable of celebrating one birthday at a time. He feels doomed by the arrival of another such officer.

He earns laughs by now and then referring to the nun as a bitch plotting to kill him.

In such a wordy play it is essential that we catch the lines particularly as there is so little action or the diversion of plot points. As is often the case with theatre of the absurd not much happens.

During the first act we were at a loss with poor seating on the side in a theatre not notable for the quality of its acoustics. It was challenging to catch the drift of the play particularly as the lines were not often delivered in our direction.

At the interval we were offered better seats in the front of the center section. It made a world of difference as the second act flew by in a hilarious and delightful blur. We finally caught up with the quirky characters and what made them tick. Prior to that we really didn’t know why people were laughing.

One of the delights of following Shakespeare & Company over the years is the opportunity to see its actors and directors in ever changing contexts. You know their work and delight in seeing how it is adapted to the latest production.

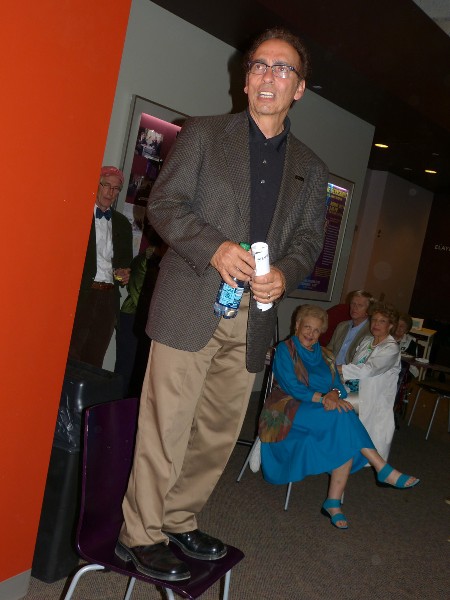

While Stoppard is always difficult, an acquired taste, either literary, raw red meat or steak tartare depending on one’s palate, it was a bold and challenging choice for the director Kevin G. Coleman. As he told the audience during the cast party, having seen another production, he was convinced that they could do it better. He also predicted that the play will improve during its run through September as the actors perfect their timing and get to develop the dimension of their characters.

We would like to suggest some notes, including Epstein not dropping the second half of lines, but that is not our role.

There is much to enjoy about the play even though, typical of Stoppard, while being wafted along by all that clever prose, we are often adrift in knowing what it’s all about and where it’s going.

In that regard Coleman has made the most of the conundrum keeping a fast clipped pace while attempting to delineate and define the subtle quirks of the characters.

These veterans of World War I have seen their share of horrors, hence they are Heroes. It is perhaps too easy and convenient to say that they display post traumatic stress disorder. In 1959, the time of the play, not much was known about that syndrome and it would be a stretch to say that was the intent of Sibleyras.

But the three characters reveal a spectrum of responses to combat that was hideous beyond description. For that we have Erich Maria Remarque’s iconic novel “All Quite on the Western Front.” These three are the survivors of that horrific context.

Because of a fragment of shrapnel in his head Philippe is prone to blackouts. These are played by Ingram with hilarious impact. Attending the funeral of a colleague, who has committed suicide, he returns with a mud splattered suit. It seems he passed out and fell into the open grave. Pretty funny.

While emerging from the spells he mutters “Get them from the rear, Captain.” We assume it is a memory of battle. It turns out that Captain was a nickname for a girlfriend he visited on leave from the front. There is a nice moment when the true meaning of the phrase is revealed.

Gustave, the most decorated of the three, is a man of action now resigned to doing nothing. A fairly recent arrival at the hospital he describes his life with a simple mantra of “Room, terrace, tepid soup, beddy-bye.’’

While fond of gazing off into the distance with binoculars, as if surveying the terrain of the battle field, he is phobic and unable to leave the terrace. In a fantasy of visiting town, like Henri who takes a daily “constitutional,” he has to rehearse how to greet passing strangers.

The sanctity and privacy of their terrace is threatened by plans for renovation. The three are stirred to action which advances the plot to escape to the poplars and beyond.

“We have to defend the position!’’ cries Philippe. Henri agrees “Barbed wire! Sandbags! Trenches! It’ll be like old times.’’

Of the three Henri, a heavy man with a bum leg, seems the least delusional. While going along with the fantasies of his comrades he tends to inject pragmatic, deflating, reality checks.

During his daily walks into town he seems smitten by a school teacher and her young female charges. Gustave’s comments are smarmy as well as jealous. “He’s a born enthusiast,’’ he comments. “When he’s dead, he’ll be an enthusiastic corpse.’’

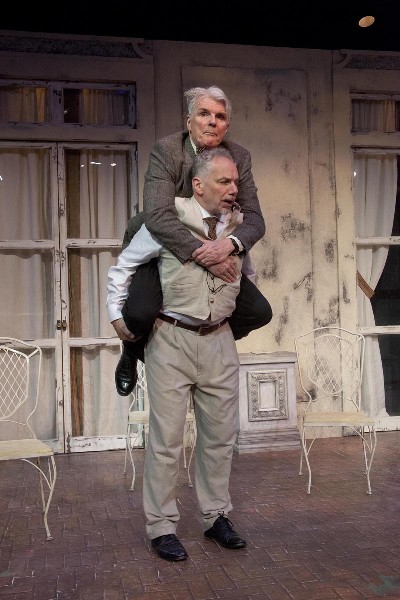

The pace of the second act accelerates around Gustave’s paramilitary plot to escape. Esther Van Eek has given him an officer’s great coat and cap with a perky bit of black feathers. He is poring over a map of the area and its obstacles including fording a shallow stream. There are no bridges and he suggests carrying the other men. To demonstrate he hoists Phillippe who, gotcha, passes out. That brings the house down.

Then there is a folderol about being tied together with rope. In this case, a garden hose which Coleman directs with comic brilliance. It's total cackhanded and just hilarious.

What about the dog which Gustave insists on bringing along? Phillipe in delusional moments insists that its alive while the more grounded Henri does not. When Henri, who has found blankets for the excursion, is dead set against including the dog Gustave is furious.

“Have you got something against dogs?’’ he asks. Henri responds “No. Only against lugging around 200-pound bronze statues of dogs.’’ Gustave replies “And that’s your only objection? That he’s made of bronze?’’ Henri says “Yes. That’s the only thing I’ve got against him.’’ Gustave relents “Well, at least your frankness does you credit.’’

And so it goes in this perfectly ridiculous mondo cane. Woof.