Andy Warhol in Iran by Brent Askari

Hit Premiere at Barrington Stage Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 09, 2022

Andy Warhol in Iran

By Brent Askari

Directed by Skip Greer

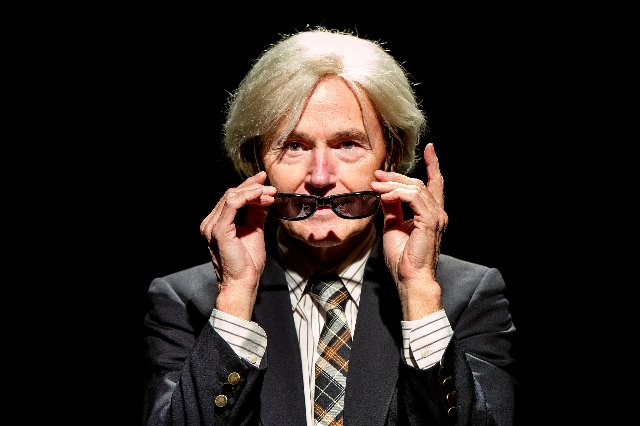

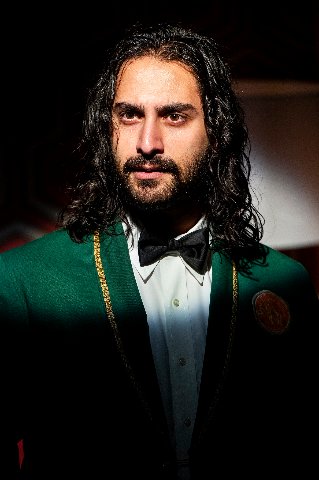

With Nima Rakhshanifar and Henry Stram

Scenic designer, Brian Prather; Costumes, Nicole Wee; Lighting, Joyce Liao; Sound, Dan Roach; Wig and makeup, Mary Schilling-Martin. Projections, Yana Biryukova.

Barrington Stage Company

St. Germain Stage

June 2-25, 2022

In Andy Warhol in Iran, a new play by Skip Greer commissioned by Barrington Stage, the vocal cadence of Henry Stram as Andy Warhol is off key.

With insouciant, faked self-effacement, stutter-step delivery, smirks at his own riffs and put-ons, Warhol’s pitter patter was distinctive and should rightly have been patented. It was a significant part of how the artist and master huckster marketed and promoted himself.

With the deadpan artist the persona was the sizzle that sold his steak.

Or in Andy parlance “Brought home the bacon.”

Stram joins a long list of those who have portrayed Warhol including David Bowie. There seems to be endless fascination with an enigma. Arguably, Andy through his museum, estate, and foundation is now more rich, famous and influential than ever.

He grew up poor and sickly in Pittsburgh. The death benefits of his father paid for his art education. Through illness he was prematurely bald and had bad skin. He was in fact quite homely but accessorized with clear plastic glasses, wigs and makeup. That made him easy to impersonate. Warhol employed a double who made speeches and appearances for him when he didn’t want to leave New York.

Andy was clever with wigs and took to wearing silver on top of a black one. That layering made it appear that his roots were showing. My friend Gerard Malanga, who bunked with him on the road, swears that he never saw Andy without a wig. During lunch breaks they walked home from the studio where Andy’s mother, Julia, made lunch. Often that entailed a can of Campbell’s soup, one of his iconic images. He also used Julia’s unique and florid handwriting as part of his graphic design. As devout Catholics they attended mass each Sunday during the 18 years she lived with him in New York.

Warhol had the schtick of being anything you wanted to him to be. When asked a complex question his standard and gobsmacking answer was “Yes.” As to how do you make your work, he responded “I fake it.” He was the master of passive resistance. Facing the media, reporters or critics essentially framed interviews which Andy cleverly affirmed. The media always got what they wanted though the “answers” were typically enigmatic.

Or, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol from A to B and Back Again.

When queried about war, politics or tough questions he would demur that he didn’t know and that the subject was too “abstract.” That was his standard response to anything that stumped him or attempted to make him take a position on a difficult issue.

He attracted an entourage dubbed “The Factory.” They comprised queers, drag queens, druggies, socialites, artists, dropouts, the poet Gerard Malanga, and whoever showed up for a screen test and proved to somewhat interesting. Andy was a magnet for beautiful boys but was in a long-term, committed relationship.

Each night he fed a menagerie of freaks on his running tab at nearby Max’s Kansas City. Wisely, its owner Mickey Ruskin took art from Andy and other artists to settle bills. Upstairs at Max’s, which served steak, lobster and chick peas, was a room where The Velvet Underground, the New York Dolls and other bands performed.

Nobody got paid other than Gerard and Paul Morrisey who directed some films. The entourage fed him ideas, starred in the films, and in that manner earned their fifteen minutes of fame. He loved gossip which he shared each day with Brigid on the phone.

Valerie Solanas, a deranged radical lesbian thought he owed her more. June 4, 1968 she walked into the factory and point blank shot him. The play explains that she was angry that he did not produce her play. In fact, he had not returned or acknowledged a film script that she had submitted.

As he explains to the waiter Farhad (Nima Rakhshanifar) a radical revolutionary holding him captive in a hotel room “She ran a movement Society to Cut Up Men (SCUM) but was its only member.”

With irony his beloved Daily News ran the story inside. He got bumped off the cover by the assassination of Bobby Kennedy. He fought for his life and was legally dead for a couple of minutes.

“Fame saved me” he explains. When the doctors realized who was on the table they redoubled their efforts.

After that Andy was never the same. He stopped hanging out with freaks fearing another incident. The movies, which cost a lot and took in little, were suspended. With a midlife and career crisis he reinvented himself. He made a series of silk screen paintings of Mao, Marilyn, Elvis, Liza, Elizabeth Taylor, Mick Jagger and other celebrities.

Hanging out with socialites and billionaires at Studio 54 he came up with a cash cow. Shooting Polaroids, with assistants he transformed them into silk screen portraits in the manner of the iconic Marilyns. While these portraits of the megarich brought home the bacon, lots and lots of bacon, they were generally commercial, uninspired and the aesthetic lowpoint of his storied career. Truth is most captains of industry are not very interesting or inspiring people. Warhol's commercial portraits reveal that. Seeing them gathered at the Whitney Museum was a painfully dreadful experience.

Andy earned some six figures plus for these hack works. Some of his sitters ordered multiples for homes and offices. It was easy money for which he sold his soul.

As Andy puts it in this play “I have a lot of mouths to feed.”

The back stories of the really bad guys he sucked up to for commissions proved to be too “abstract” for him to comprehend. So he was pals with Imelda Marcos and attended a White House reception for the Shah of Iran.

No doubt Andy would have loved the Trumps, particularly Melania, and been a frequent flyer to Mar y Lago. Basically, Andy was a trend and taste maker devoid of a social conscience. He was the Switzerland of art which is to say frequently cheesy.

Which is how Askari focused on a hotel room in Tehran (an apt set by Brian Prather). That’s a fact although there is no record of a botched attempt to kidnap him. It’s also true that he mostly spent time ordering room service. It was too hot for tourism. “Can you believe it you can order a half pound of caviar for just nine dollars.”

Set in 1976, the play imagines events when the artist was invited to Iran by Fereydoun Hoveyda, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, to create a portrait of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s wife. Warhol met the Empress Farah Pahlavi, whom he took Polaroids of during his visit. He was accompanied by his manager Fred Hughes and Bob Colacello, Warhol’s biographer and then editor of Warhol’s Interview Magazine.

Things go south for 80 minutes when the waiter arrives with the caviar. With a knock on the door Andy asks to just leave it outside. Farhad insists on coming in. “You have to sign for it. That’s hotel policy.”

Once in he pulls a gun and demands cooperation. The plan is to kidnap him as a device to get world attention for the cause of ousting the Shah. A car is coming, as Farhad constantly looks out the window. It never does.

Initially, they have nothing in common. Farhad refuses to answer questions while Andy mugs to what he hopes are listening devices.

Andy offers money or a part in a movie. “I can make you famous” he argues. Farhad, a committed revolutionary, isn’t interested in fame or fortune. Andy is flummoxed, “Everyone wants to be famous.”

There is reversal as they find commonality. They even compare their scars. Farhad had been tortured by the Shah’s savage Savak which killed his father as well as countless dissidents. As Andy comes to identify with his captor he muses that he might be a victim of Stockholm syndrome.

As a device the two characters from time-to -time step out of the play to narrate projections (Yana Biryukova) which provide backstories. That of Farhad was particularly riveting as it provided a capsule of how the Shah with the CIA and MI5 ousted the rightful democratic president who died in prison. For that support, he forked over 60% of Iran’s natural resources and petroleum forming what became British Petroleum. The major oil companies shared the wealth of Iran.

It was good to have that brief flashback and unvarnished exposure of America’s role in global imperialism.

Overall we loved this new play. The actors were compelling in their roles and the direction of Skip Greer navigated them nicely. There were twists and turns that kept us engaged. Stram was a very good if not great Warhol. He was actually too pretty with none of Andy’s awkward enigma. This was a play after all and not a documentary. To portray an authentic Andy would have added another half hour at least.

This production kept it tight and sweet. The play is the first hit of the summer season. Jump fast for tickets to a fun and entertaining evening in fabulous downtown Pittsfield. After being shut down for two and a half years Julianne Boyd was thrilled to welcome back audiences. We laughed all the way home.