Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963-2010

German Master Surveyed at MoMA

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 03, 2014

The German artist Sigmar Polke (1941-2010) is the focus of an eclectic, jam packed, acid trip, installation of 260 works in every conceivable media Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963–2010 on view at the Museum of Modern Art through August 3.

Responding to the idea of alibi, implying guilt and crime, let me start by fessing up that what follows is not a review. Given the sprawling, messy diversity of the work, and a limited time to observe and digest it in situ, that’s just not possible.

For a more cohesive critical analysis, nice tries but mostly wide of the mark, you are best to goggle reviews by the usual suspects. They have jobs and get paid while I don’t. So, no I haven’t read the catalogue, or done the months, arguably years, it would take to navigate through the fertile but often explosive mine field of Polke’s singularly restless and brilliant oeuvre.

To accomplish that one would need to conjure the shade of Virgil to guide us through the circles of the artist’s mind, often fueled by hallucinogens, hippie lifestyle, and peripatetic global wandering camera ever at the ready.

Over the years when seeing one work at a time, or a related group in an exhibition or magazine article, there was the fleeting conceit of thinking that I had a grasp of the work.

The experience of a staggering perambulation through the dense galleries of MoMA with their bombardment of different and separate vectors, proved that I was dead wrong.

It would take a dedicated lifetime to decipher the work. One would have to charge in, confront and slay the minotaur, then follow the unwound string back through the labyrinth out into the clear light of day and plausibly restored sanity.

One cannot think of Polke, or the other great German artists and filmmakers, without plunging down the rabbit hole of the rise and fall of the Third Reich the aftermath of which so informed them.

During a week in New York, having left my phone at home, in a room with no TV, I finally read Hannah Arendt’s provocative and controversial “Eichmann in Jerusalem: The Banality of Evil.” Arguably that is a more fertile beginning to understanding Polke’s ”Alibi.”

The Post War era and global defeat of fascism had an enormous and empowering impact on American arts, consumerism and political leverage. Our branding from Coca Cola to cigarettes, blue jeans, Hollywood and television sit coms, multi colored gas guzzling cars with fins dominated global markets.

In the fine arts it was encapsulated by Irving Sandler’s “The Triumph of American Art” or Serge Guibault’s “How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.”

In Dusseldorf the former Luftwaffe pilot, Joseph Beuys, was a shaman and teacher of social sculptures with a grimly ironic, mordant humor. His influence on students informed the diverse works of Gerhard Richter, Blinky Palermo and Polke. Add to that Anselm Kiefer and Martin Kippenberger. In film consider the brilliance of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog.

The enormous weight of history was borne on the shoulders of these artists. Perhaps it was the obstacle and resistance requiring enormous strength and character to overcome that so informs the energy, gravitas and originality of their work.

On the other end of the arc of their creativity there was America to contend with.

In a 1974 performance installation in New York’s Rene Block Gallery Beuys took this challenge head on in the piece “I Like America and America Likes Me.” He was met and delivered back to the airport in an ambulance. His intention was not to see even a glimpse of America other than the interior of the gallery. There he was confined with a coyote and some newspapers for it to soil. These were signed and sold. Wrapped in his signature felt, which the wild animal occasionally gnawed on, the artist fended off with a cane. Eventually they settled into a truce and are seen relaxing on other ends of the space. The frayed felt became a relic and valued artifact of the encounter.

An avowed pacifist Beuys refused to “see America” until the United States ended the war in Vietnam. At which point the Guggenheim mounted a retrospective which he attended.

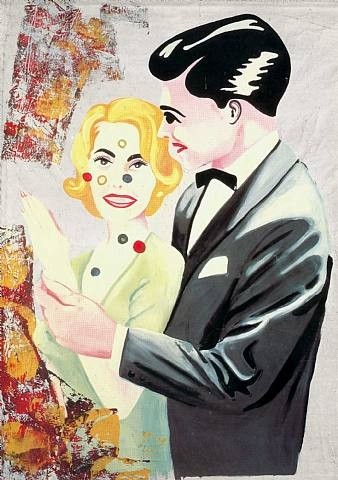

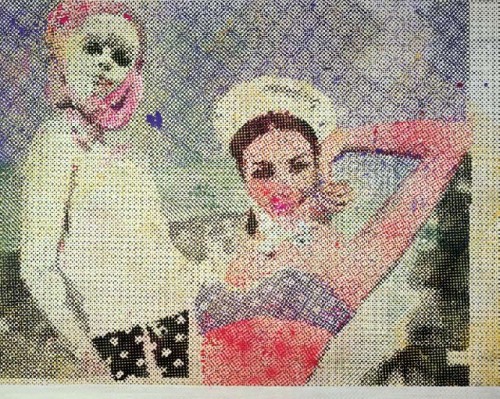

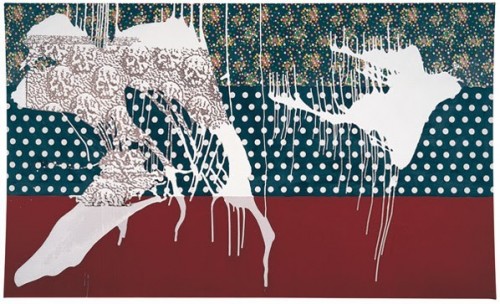

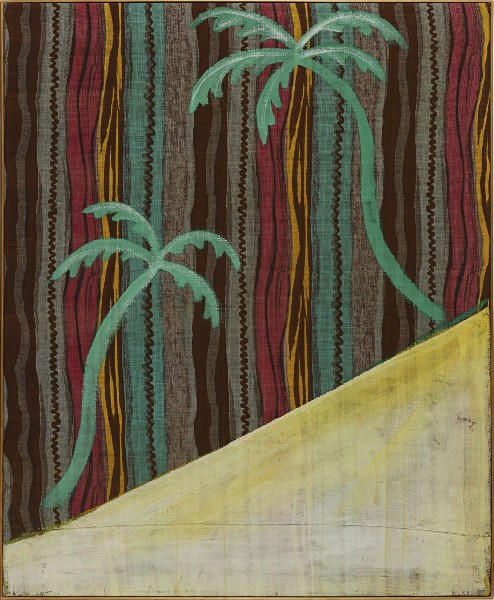

The young Polke, in some of his most identifiable works, spoofed Pop art with the invention of Capitalist Realism. Where Roy Lichenstein used screens to scrub his signature ben day dots onto canvas, for Polk, the dots were laboriously hand painted. These most accessible of his works often look like mistakes or misregistered printings of fashionable and sexy women. There were deadpan renderings of consumer items or folded shirts.

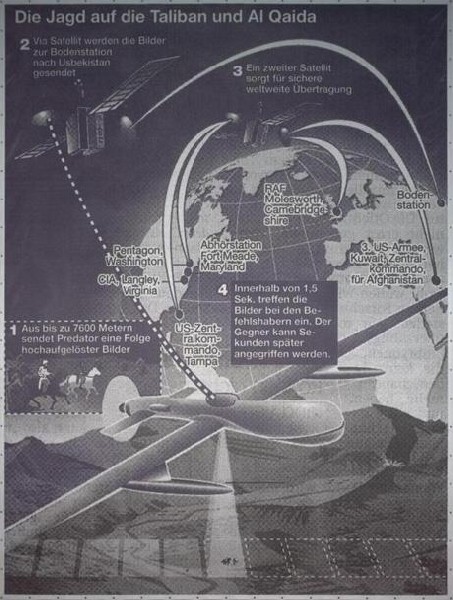

Throughout the oeuvre there is political commentary. From the earliest phase swastikas appear as they did in works by Kippenberger. Under the Western German government it was against the law to depict Nazi symbols. In a stunning work he depicted the global path of military drones and the post 9/11 hunt for Al Qaeda.

Where Lichtenstein created a successful career of this niche idea Polke moved on. And on. And on.

Critics are divided on Kathy Halbreich’s MoMA installation. Opinions range from brilliant to disaster. The prominent critique is that it could have been edited for more cohesion. Or given the space that it deserves with another floor, additional galleries, or perhaps a shift to PS1 a vast satellite of MoMA. Truth is this is the best we will have of Polke for at least a generation.

Instead of wall labels the museum has provided a free booklet with diagrams of the installations and identifying check list. For me that didn’t matter as I don’t read wall texts and labels only occasionally. So I liked this approach that encourages visitors to experience the devastatingly complex installation as a totatality.

To use the correct German term, a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art.

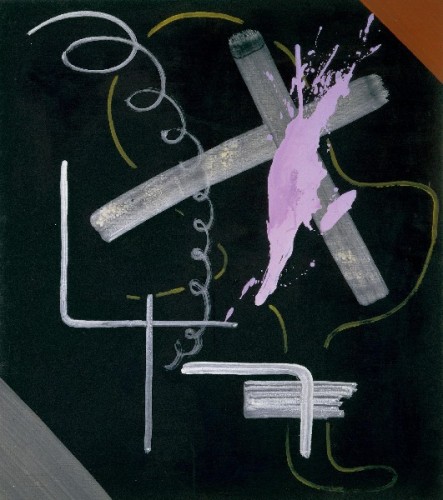

Careening through the galleries we encounter large, major works, as well as scribbles, the pencil shavings of creativity. There are amateurish home movies of the artist cavorting with friends. All of this totally disarms our notions of a great artist. On any given day he was or wasn’t. Mostly he pokes a finger in the eye of the art world and its critics who have taken the bait of trying to explain him.

Better to just go along with the trip.

There are signature pieces which I have encountered in the past and thought I understood.

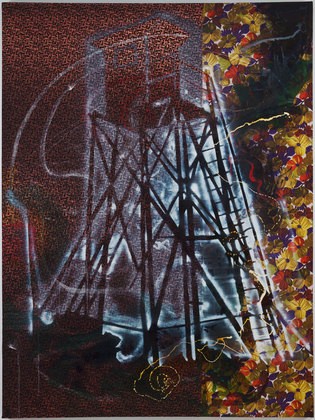

Years ago I was astonished by a piece displayed at the ICA that had been purchased by Charlene Engelhard. It depicted the profile of a concentration camp guard tower and a barbed wire fence. Typical of the period of the work it was painted onto a canvas stretched with sections of commercial cloth. This was a technique that Blinky Palermo also used to make riveting minimalist abstractions.

At MoMA we encounter several of these towers with a variety of experimental media approaches.

There is an element of alchemy as the artist worked with a variety of materials some of which are already challenges for conservators. His media included resin, dispersion paint, pure pigment, enamel, varnish, fluorescent paint, lacquer, graphite, soot, silver leaf, silver oxide, silver nitrate, applied not just to canvas but to felt, polyester, and even bubble wrap.

Some of the more attractive large works entail imagery taken from vintage illustrative prints. There are also endless photographs and altered prints.

Often there is ambient sound. Looking for the source in one part of the exhibition I found small speakers on the edge of walls defining a space. You are not intended to know that it’s there and just experience it.

Trippy.

Eventually I was coughed up and regurgitated like Jonah crawling out of the beached whale.

Today I am back to normal and trying to crawl back into the beast.

Which is like trying to remember the maelstrom of an acid trip.

There are flash backs, glowing fragments, but mostly lost forever.

Bummer.