Deep Dirt on Annie Lennox

Installation of Detritus at MASS MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - May 31, 2019

Sweet dreams are made of this

Who am I to disagree?

I travel the world

And the seven seas,

Everybody's looking for something.

As the 1983 hit single “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” with guitarist David A. Stewart and The Eurythmics states Annie Lennox is well traveled. Seven Seas indeed.

The name of the group derives from a musical term. Eurythmics is a system of rhythmical physical movements to music used to teach musical understanding (especially in Steiner schools) or for therapeutic purposes, created by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze.

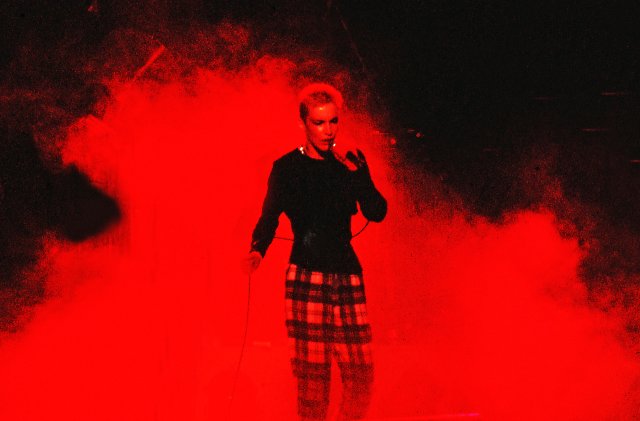

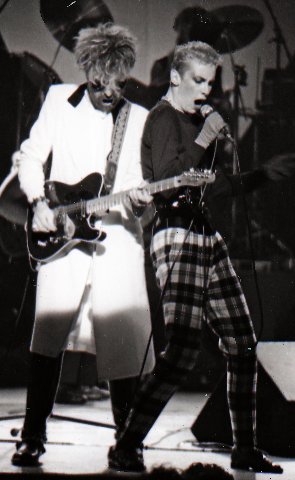

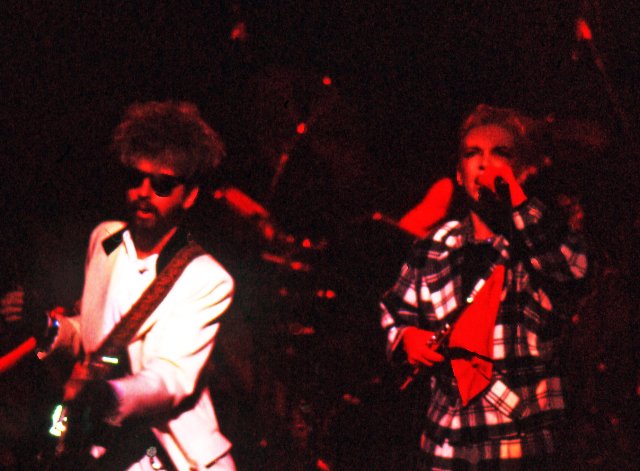

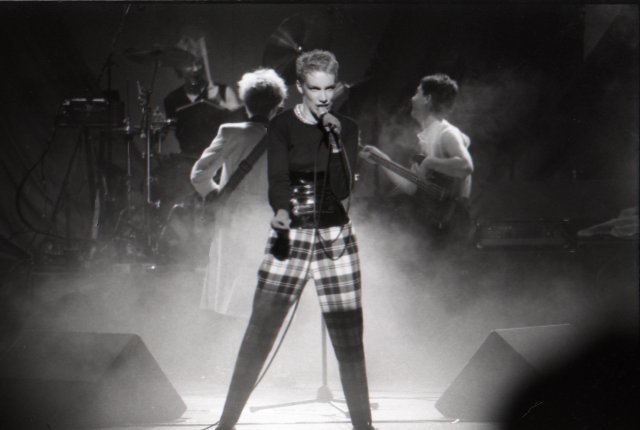

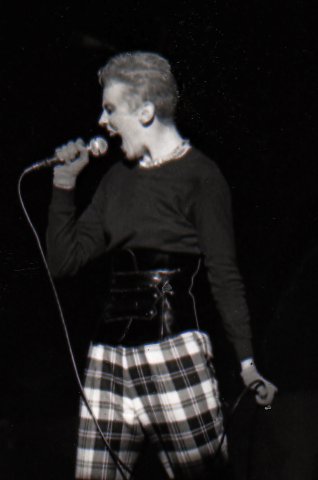

Before they disbanded in 1990, it was riveting to see them perform. The photos I took jog the memory of a stunning concert. There was the usual staging of dramatic smoke and mirrors but relatively modest by current standards. Boston’s Orpheum Theatre is small so the feeling was intimate.

Her androgynous look entailing short cropped blonde hair, plaid pants, and strident stage manner made her a superstar of the era. At one point she played a bit of flute. Mostly we were riveted by her tough as nails blues inflected delivery. The vocals were notable for their clear and punchy lyrics and catchy hooks. One felt compelled to sing along with those iconic songs.

Along the way the musician, activist and philanthropist held on to a lot of memorabilia.

“I’m a magpie of sorts—but not a serious collector,” Lennox explained to Observer. “I’ve always held a certain fascination for found objects. Anything you find in junk shops, flea markets or thrift stores. I’m drawn to the flotsam and jetsam of life: old photographs, second-hand books, tea cups and saucers, costume jewelry, whatever. Any object that comes from the past seems to contain an essence of its time.”

An eclectic selection of this material is scattered and embedded into a vast mound of earth in an attic gallery of MASS MoCA. In dim light the items comprise resonant detritus of the artist’s life. It’s possible that they mean more to the pop star and her global fans than to most visitors.

Borrowing from her best known song she has created a “dreamscape.”

The mound dominates the primary space but there are other elements. Navigating around its periphery the back end is devoid of objects. The trajectory leads us to a room with floor to ceiling, gold and platinum albums and awards. The mirrored floor reflects and seemingly amplifies the trophies. It evoked a truncated version of a packed corridor we encountered at Elvis Presley’s Graceland.

Coming back to the other side of the mound it slopes down toward an end wall that loops a selection of her videos as well as clips from the Wim Wenders film Wings of Desire. There is the soft ambient music of the just released four song, piano suite Lepidoptera.

Five years ago Lennox was awarded an honorary degree by Williams College. During that occasion she was given a tour of MASS MoCA by its director Joe Thompson. From that experience came the pitch for Annie Lenox: Now I Let You Go…

It was bundled with a benefit performance that launched the summer season during Memorial Day weekend. The event sold out with tickets from $100 to $1000. That was pricey to experience her at the packed Hunter Center during a day long event with otherwise free admission.

There was a huge and enthusiastic turnout but mixed responses to her installation from those we spoke with. Endorsement of the site-specific piece was conveyed in inverse proportion to depth in contemporary art. That ranged from fans who were confused but awed, to effete aesthetes conveying affected apathy. Among the latter were versions of been there done that.

Conceptually, there was nothing new or particularly engaging about this work. Its sources are all too familiar. There is a long tradition of the found object and fetish installations from Marcel Duchamp in the early 20th century to now. It’s a well traveled highway. A better version of this genre was Mark Dion’s “Octagon Room” installed at MoCA in 2015.

When the young Lennox studied music she was equally interested in the fine arts. That’s a familiar conflict. Many of our greatest rock stars are multi-valent in the visual arts from painting to conceptual work. Genius in one medium morphs into another. The theme of musicians as artists would surely be a blockbuster exhibition. It might easily fill MASS MoCA.

This is not the first major museum project for Lennox. A version of what is on display in North Adams was The House of Annie Lennox at the Victorian and Albert Museum from 15 September 2011 to 26 February 2012. Not having seen that exhibition one assumes that the current project is more ambitious and cohesive.

As a trope the massive mound of earth makes sense. It is a better approach that putting all those small items in a daunting array of vitrines. That’s so, well, V&A. If you have visited that venerable Victorian London museum it evokes the cluttered attic of the Industrial Revolution. Contemporary designers strive for ways to liberate visitors from viewing a plethora of objects embalmed behind glass. In this development designers, with often spectacular results, enjoy equal status with curators. They are the true miracle makers.

The installers and fabricators at MoCA are renowned for helping artist to take ideas sketched on cocktail napkins to full blown, stunning installations. Much of that entails the genius of problem solving. Simple ideas can be excruciatingly difficult to execute.

There is a Myth of Sisyphus aspect to the Lennox project. One imagines and feels for the MoCA crew that had to lug all that dirt to create the mound. I wondered if they created an armature over which to create a layer of earth. Or is it all just dirt or potting soil. In the context of a museum, surely research went into using clean dirt. At issue is preventing mold and damaging spores during the many months it will be on view.

What comes with celebrity status is the opportunity to work outside the box. That cuts to the intentionality of the artist.

At 64, this work resonates with issues of a life examined. Family memorabilia references working class roots in Scotland. There are the progressively larger shoes of two now grown daughters. There is the sewing machine of her mother and clothing she made. Her father is remembered with his medal, watch, chanter reeds, and beer glass. There are cassettes, CDs and travel souvenirs. Literally topping it off is a piano cresting the mound of dirt.

In the dim light you have to bend down to discover the many items. It takes time and commitment to see and process them all. To do so entails a meditative mode. Another approach is to take it all in through a sweeping panoramic view. Time spent with the installation becomes a marker of appreciation.

With premonitions of inevitable demise Lennox with this legacy project, is getting a head start on what Somerset Maugham expressed as “The Summing Up.” It’s an endemic impulse of the human experience. That’s a particularly acute compulsion for artists seeking to make sense of a life of creativity. The options are to document and archive the ephemera or chuck it in the dumpster. Too often lives end in yard sales.

An interesting question is what happens when the exhibition is deinstalled? Some years from now will her daughters treasure their baby shoes? Or will it all go into boxes in the basement of the V&A or some other museum/archive.

To that point the installation displays a truism "Naked I came into this world, and naked I shall leave." As she told a reporter “I'm here now! We will all die. Death is there in the exhibit because it’s the guarantee for us all. It terrorizes us but we all need to come to terms with it because there are other cultures who have incorporated death. The Indonesian culture for example lives with that parallel notion that death is there. Ooh, it makes me emotional to think about!”

Indeed all is vanity but few if any of us get to express concerns for our mortality in such a public and monumental manner. For most it’s to sleep, perhaps to dream.