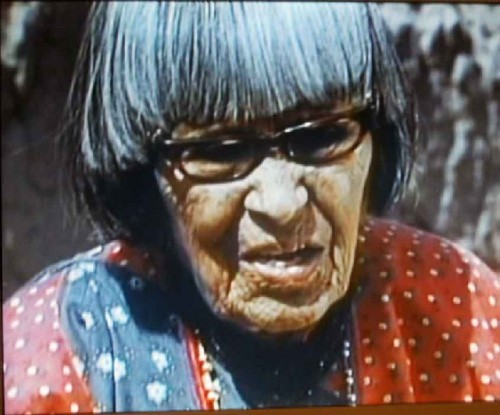

Pueblo Potter Maria Martinez

In Depth Collection of Denver Art Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - May 31, 2010

The Denver Art Museum has one of the most in depth and renowned collections of the Art of the Americas with an emphasis on Pre Columbian and the Native arts of the Western United States. There are also stunning examples of Caucasian views of Native people as well as ancient to contemporary works by leading Native American artists.

Maria Montoya Martinez (1887 – 1980) is one these masters. She learned to make pottery from her aunt Nicalosa and become one of the most skilled of the San Ildefonso Pueblo artisans. When she learned traditional techniques the craft was on the verge of extinction. Cheap enamel pots and storage vessels had eliminated the need for creating pottery.

Archaeologists had found shards of ancient pottery including a distinctive black ware. This discovery was made by Professor Edgar Lee Hewett in 1908. As the most talented potter in the community he approached Martinez about the possibility of creating contemporary examples of black ware that might be used by museums to provide reproductions of ancient vessels.

Much experimentation followed and initially the results by 1913 were crude. She did not want to show them. But when examples were seen it created such excitement and interest from collectors that she was encouraged to continue to develop the technique. Her husband Julian, who died in 1943, provided the painted decorations. They derived an unique process. through reductive firing the pot transformed from red clay covered with a burnished slip and painted to have matte decorations. There was a contrast between the polished black surface and the matte patterns. Julian emulated many of the ancient designs. No glazes are involved in the process.

When Julian died she worked with her daughter in law, Santana, and other family members. While she was reluctant to teach her assistants learned through observation. This has resulted in the continuation of her innovations.

Visiting major American museums it is common to find examples by Maria and Julian in collections. But in the Denver Art Museum we encountered a trove of her work with a number of collaborators in different styles and techniques. In addition to her signature black pots there were other more polychromatic designs and a variety of shapes.

There was also a video presentation that demonstrated the process of creating and firing the black pots.

It started with an annual gathering of clay and volcanic material in the vicinity of the pueblo. First she scattered corn as a gift to the Gods and a prayer for their assistance. “I take only as much as I need" she said. The clumps of dry clay were sifted and gathered onto a spread out cloth. This material is then stored, dried and aged.

Two piles of clay and volcanic ash are created and a well made in the middle. A critical amount of water is added and the material is mixed and kneaded into lumps of clay. These are then set aside to cure for a couple of days.

There is no wheel involved in forming a pot. A pancake of clay is pressed into a curved base. This is either hand made or used from a broken pot. Coils of clay are added and pinched to work out air bubbles. This is continued until the desired size and shape is formed. Martinez was noted for working quickly with dexterity, skill and confidence. The shape is further refined with special pieces of gourd.

The completed pot is set in the sun to dry. The surface is sanded to a smooth texture. Then a slip is applied. This is polished while wet using special river rocks. Some were passed along from her aunt and continue to be used by family members. The slip has a special mineral content that when fired results in the black pottery.

The polished pot is then passed on to the painter and decorator. The most prized examples were painted by Julian but now others continue the techniques that he innovated. In the video she worked with her son.

He then set the pots upside down, densely packed onto a raised metal screen. Strips of cedar wood from local trees are placed underneath as kindling. Pieces of scrap metal are placed on top and around the pots. There are vents left which control the heat of the fire. On top and around the mound are placed pieces of dried cow dung. This becomes the fuel.

When the kiln is fully stacked and ready a designated family member lights the cedar. This results in a quick and intense heat as the dung ignites. When the heat reaches a critical degree determined by skill and instinct it is quickly smothered by pouring on fresh manure and ash.

In the film Maria’s son worked with the fire and smoke for a couple of hours. The mandate is to not let it ignite into an open flame. The smoke and heat are critical to creating the oxidation of the slip into a black surface.

This seemingly crude process apparently allows for far more control than is possible with a commercial kiln.

When the mound cools sufficiently the metal is removed and the pots are pulled out using a stick. In this firing none were lost.

Original pieces by Martinez are rare and much sought after. Checking on E Bay we found pieces selling for between $3,000 to $14,000. It is assumed that rare and museum quality examples sell for a lot more.

During their lifetime Maria and Julian received many honors and awards. She was among the greatest and most inventive craft artists of her generation. Much of the vitality of contemporary native pottery stems from her inspiration.